Position 63 from the sheet of 100 #C3a stamps purchased in 1918 by William Robey is, in my opinion, the Jenny Invert with the most tantalizing history.

Discovery of the Inverted Jenny

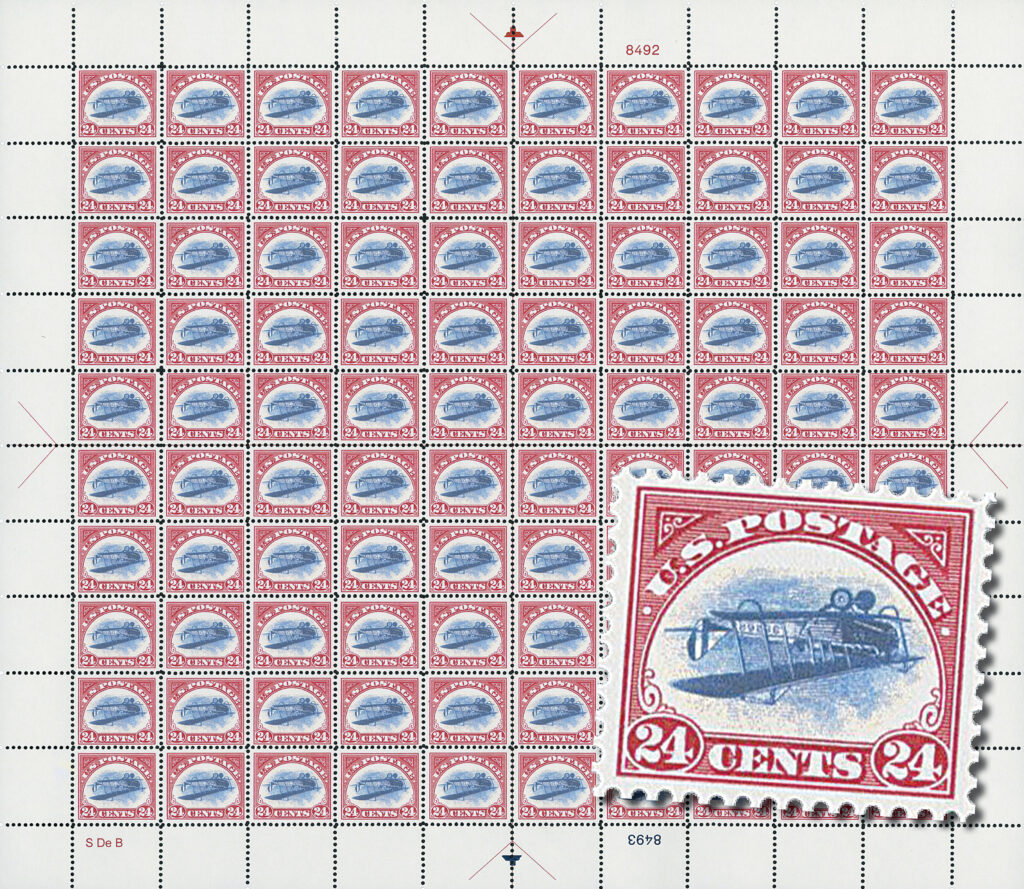

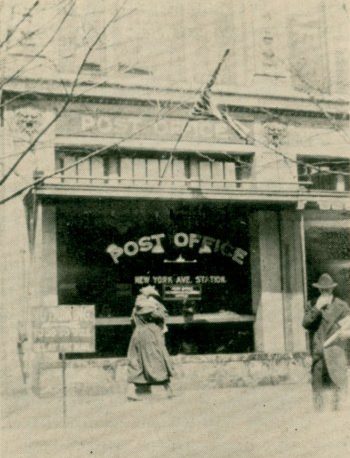

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing was in a rush to produce America’s first airmail stamp. Because the stamps were to be bi-colored, each sheet would be fed through the press twice – once to print the red frame and a second pass to print the blue vignette. In the rush, nine of the 20,000 sheets printed had been hand-fed through the printing press upside down. The mistake created an inverted vignette and positioned the plate number on the bottom selvage. At some point, eight sheets were found in the BEP office and destroyed. However, a single sheet made its way to the New York Avenue post office branch in Washington, DC.

At the age of 29, Robey was an experienced collector of error stamps and knew the potential for inverts associated with bi-color printing. On the same day printing began on the stamps, Robey advised a fellow collector, “It might interest you to know that there are two parts to the design, one an insert into the other, like the Pan-American issues. I think it would pay to be on the lookout for inverts on account of this.”

Shortly after noon on May 14, Robey entered post office branch on New York Avenue in Washington, DC, and asked for a sheet of 100 of the 24¢ airmail stamps. When the unknowing clerk placed the sheet of inverted stamps on the counter, Robey said his “heart stood still.” After paying for the sheet without comment, Robey asked the clerk if he had additional sheets. The clerk apparently realized something was amiss, closed his window, and contacted his supervisor.

Robey’s search of other post office branches was unsuccessful. He returned to his office and shared his news with a fellow stamp collector, who immediately left the office to search for more error sheets. His activities alerted authorities, who arrived at Robey’s office less than an hour after he returned from the post office. The officials threatened to confiscate the sheet of inverts, but Robey stood firm.

Alerted to the error, authorities immediately halted sales of the 24¢ airmail stamp in Washington, DC, Philadelphia, and New York City as they searched branch offices for other sheets.

Robey’s actions in the hours following his discovery suggest that he never considered keeping the inverted stamps. Instead, he contacted Washington stamp dealer Hamilton F. Coleman immediately. Coleman offered to purchase the sheet for $500 – an amount equal to more than $26,500 today. Robey declined the offer. Robey’s decision was a gamble. The value of any particular stamp is based on the law of supply and demand. Although errors in general – and inverts in particular – are highly valued, the extent of the BEP’s error was unclear that afternoon.

Because the 24¢ airmail stamps were still in production, the BEP reaction to the news of an invert was swift and certain. On May 15th, new procedures were implemented to prevent further printing errors. Shortly thereafter, still another change was made to reduce the risk. Each “generation” can be distinguished from the others by the selvage and its characteristics.

Meanwhile, William Robey raced to sell his stamps before the government made good on their threat to take them. He spent several days contacting and visiting stamp dealers. In the end, he sold the sheet to Eugene Klein. He sold the sheet that he bought for $24 to Klein for $15,000 – a 62,500% profit over the purchase price! Days later, Klein would sell the sheet to Colonel Edward H.R. Green for $20,000. They broke up the sheet and numbered each stamp, which has allowed generations of stamp collectors to trace the ownership of each stamp. Over the years, the Inverted Jenny has become a part of Pop Culture, appearing in TV shows and films, like The Simpsons and Brewster’s Millions.

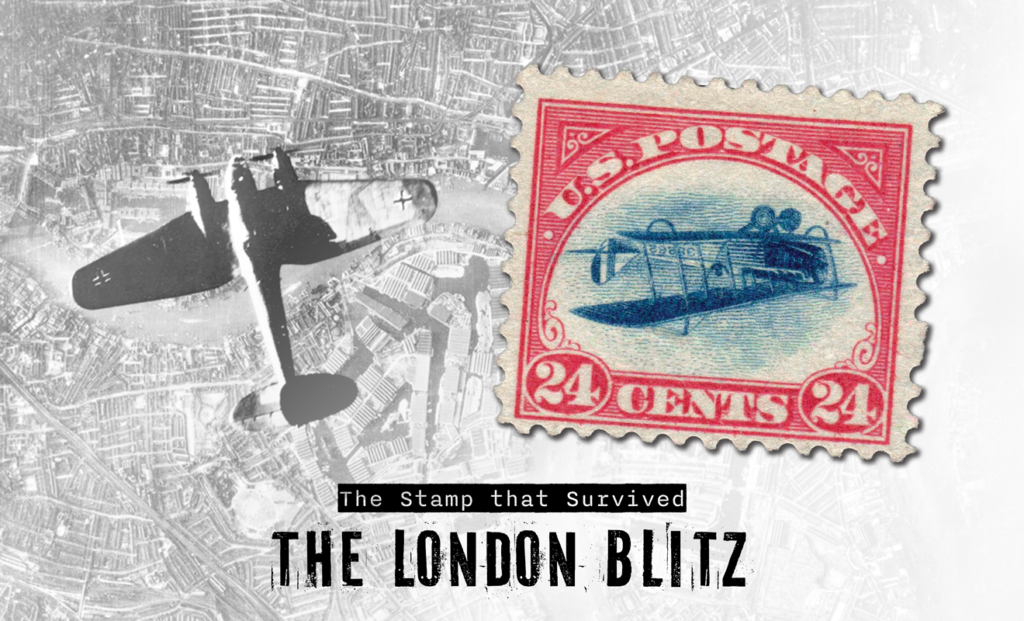

A Survivor of Fire, Bombs, and Flood

Position 63’s remarkable journey took a fateful turn during one of the darkest chapters of the 20th century – the London Blitz.

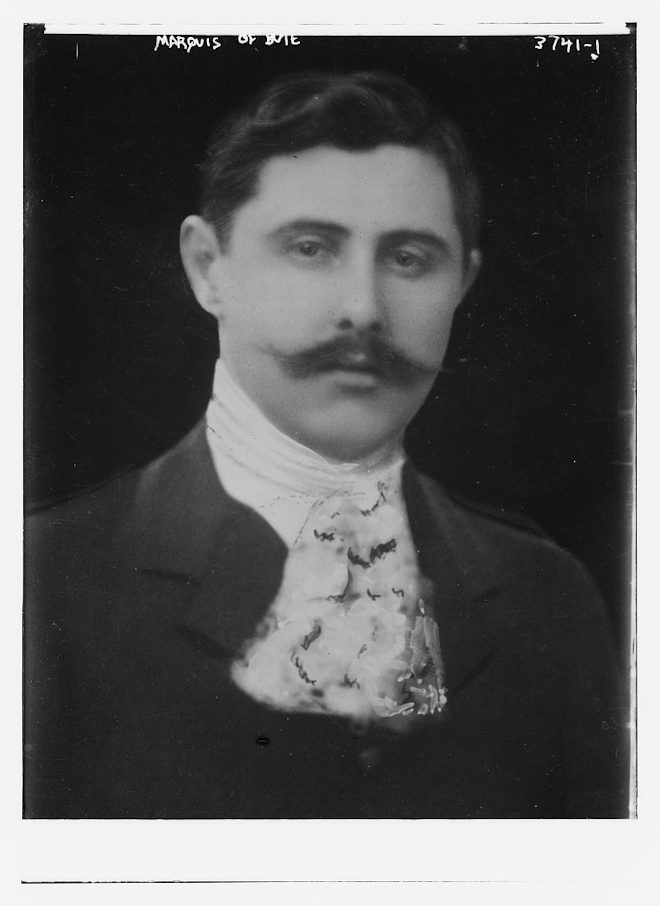

4th Marquess of Bute

Its owner at the time, John Crichton-Stuart, the fourth Marquess of Bute, was a passionate philatelist. Like so many Londoners during those terrifying months of 1940, he was deeply concerned for the safety of what he cherished most. The Nazis had begun their sustained bombing campaign over London in September of that year – targeting factories, railways, churches, and homes. Night after night, the city was plunged into flames and chaos as air raid sirens wailed and fire crews fought to save what they could.

The Marquess, fearing for his prized collection, had it stored deep underground in the vaults of the Chancery Lane Safe Deposit – five stories beneath the city streets, behind thick concrete and steel. There, one might have believed, his Jenny Invert would be safe from war…

But on the night of September 24, 1940, a high-explosive bomb scored a direct hit over the vault. The building above was obliterated. Fire crews worked desperately to suppress the inferno – and in doing so, flooded the underground vaults with thousands of gallons of water. Three feet of water rushed in. Smoke, heat, and flame roared overhead. But against all odds, the Jenny survived. Soaked, but intact – its gum washed away, but its image as sharp and as powerful as ever.

History in Your Hands

This stamp is more than an error. It’s a survivor of a global conflict. It’s a witness to history. Imagine holding in your hands a stamp that endured the worst of the Blitz and emerged a symbol of resilience – a piece of the past that refused to be lost.

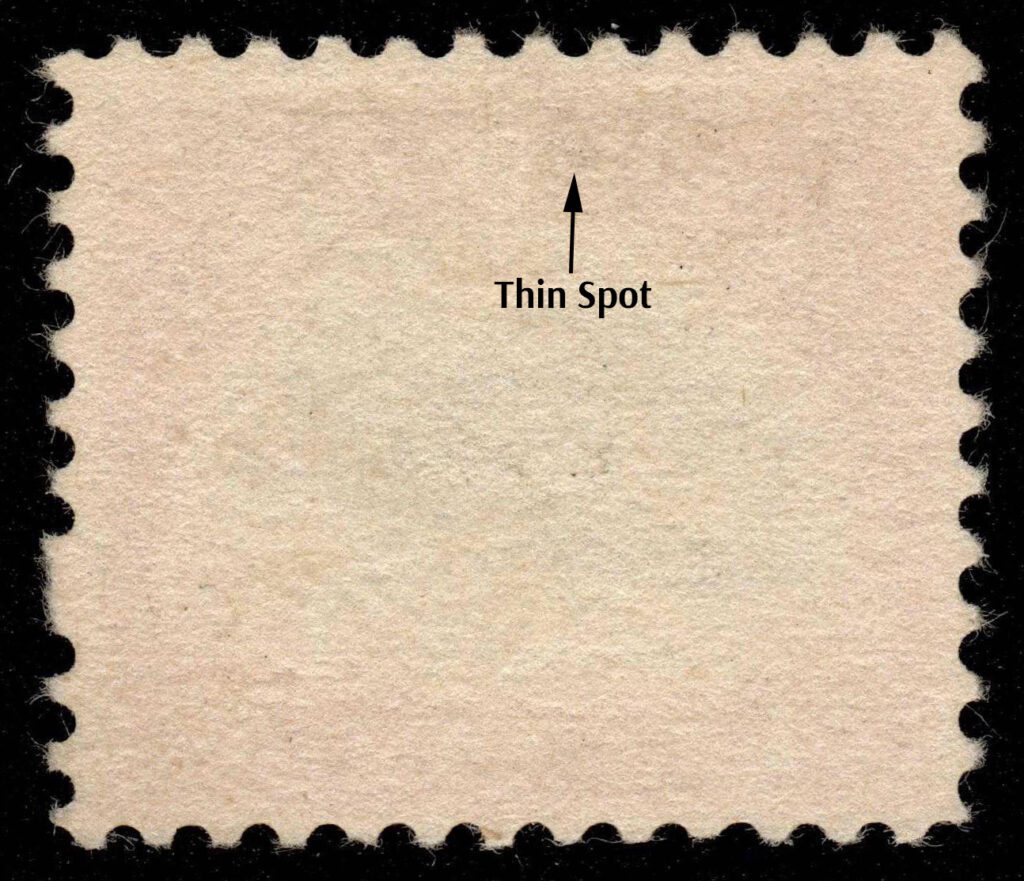

The stamp remains fresh in appearance, with fine centering and rich color. The absence of gum and a nearly invisible thin on the back are small reminders of the extraordinary story it carries – scars from a war that nearly claimed it. It’s incredible that after everything, those are the only marks it bears.

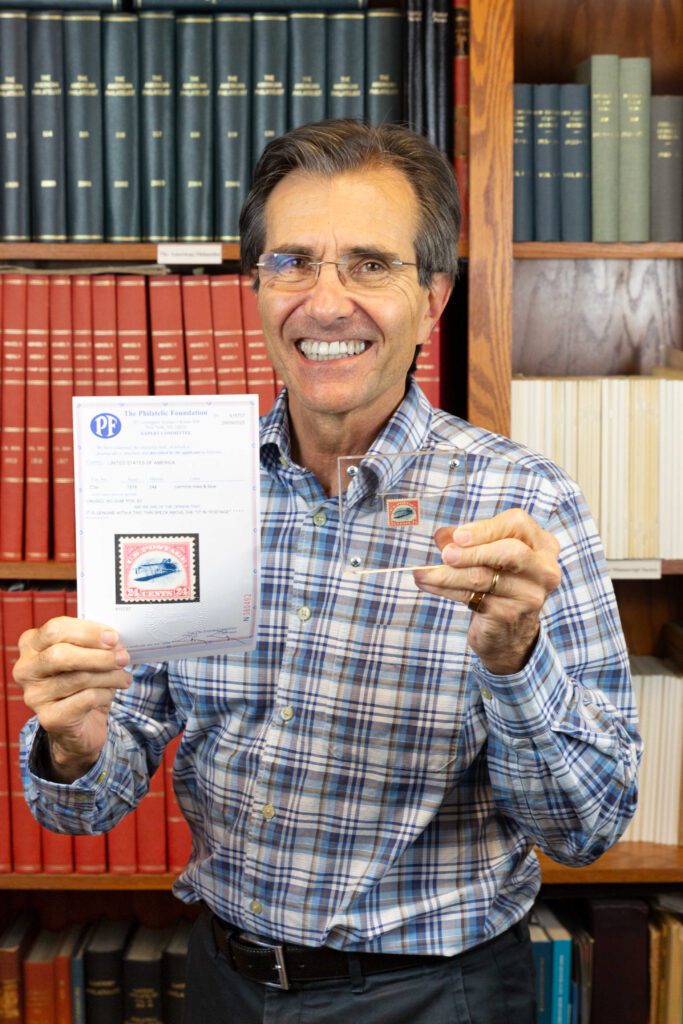

For the right collector, this stamp is priceless – especially considering it was the lowest-priced Jenny Invert available on the market in 2025. Scott values a mint example with gum at $500,000, and that figure has risen steadily from $350,000 over the past decade. While this stamp has no gum and a minor flaw, it’s still an extraordinary opportunity to own one of philately’s most iconic errors – at a fraction of what other examples might cost. Mystic sold it in late 2025 for $280,000.

Happy Collecting,

Don Sundman

Mystic Stamp Company