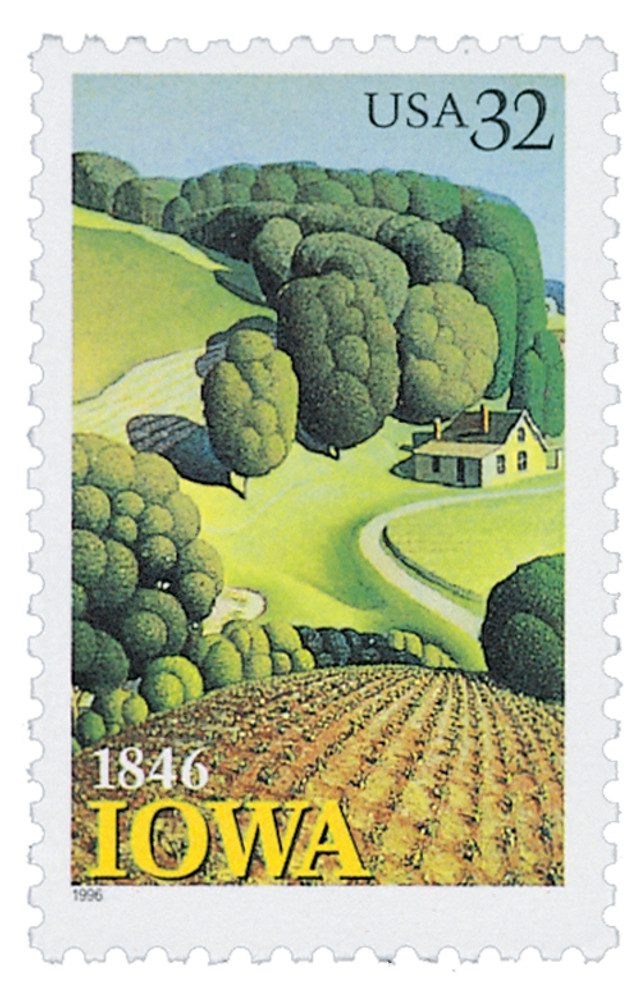

On December 28, 1846, Iowa was admitted to the Union as America’s 29th state. Known today for its rolling farmland and strong agricultural traditions, Iowa’s path to statehood was shaped by Native American history, European exploration, westward expansion, and economic change. Over time, the region transformed from Indigenous homeland to frontier territory and finally into the current state.

Long before any Europeans arrived, the land that would become Iowa was home to Native American peoples for thousands of years. Early Indigenous groups built villages along rivers, hunted bison and deer on the plains, and farmed crops such as corn, beans, and squash. Tribes including the Ioway, Sauk, Meskwaki (Fox), Dakota Sioux, and others lived in the region at different times. The rivers provided food, transportation, and trade routes, making Iowa an important crossroads between the Great Plains and the Mississippi Valley. Native American societies had rich cultures, strong spiritual traditions, and complex systems of leadership and trade long before European contact dramatically changed their world.

In 1682, French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle, reached the mouth of the Mississippi River and claimed the entire Mississippi River Basin for France. This vast region included the land that would later become Iowa. La Salle named the territory Louisiana in honor of King Louis XIV. Despite France’s claim, few Europeans actually lived in Iowa during the late 1600s and early 1700s. Only small numbers of missionaries, soldiers, and fur traders passed through the area, drawn mainly by trade with Native American tribes.

In 1762, France transferred control of Louisiana west of the Mississippi River to Spain. Under Spanish rule, settlement remained limited. One important figure during this period was Julien Dubuque, a French-Canadian trader. In 1788, Dubuque received permission from the Meskwaki (Fox) people to mine lead near the site of present-day Dubuque. He became Iowa’s first European settler and remained there until his death in 1810. His settlement marked the beginning of permanent European presence in the region, though only a small number of hunters and trappers followed.

Spain returned Louisiana to France in 1800, but French control was short-lived. In 1803, France sold the Louisiana Territory to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase. This single event doubled the size of the country and brought Iowa under American control. From 1804 to 1806, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark explored the newly acquired territory, traveling along the Missouri River and gathering valuable information about the land, rivers, and Native American tribes.

In 1812, when Louisiana became a state, Iowa was included in the Territory of Missouri. During the early 1800s, fur trading companies established posts along the Mississippi, Des Moines, and Missouri Rivers. Although traders and soldiers were present, Iowa was still officially Native American land and closed to most settlers. When Missouri became a state in 1821, Iowa became part of an unorganized territory with no formal government.

During this period, the US government forced many Sauk and Meskwaki people living in Illinois to relocate west into Iowa. One prominent leader, Chief Black Hawk, resisted this removal. The conflict known as the Black Hawk War broke out in 1832, ending with the defeat of Native American forces. After the war, Native Americans lost large portions of their remaining land in eastern Iowa. White settlers quickly moved in, eager to claim fertile farmland.

In 1834, Iowa became part of the Territory of Michigan, and in 1836 it was included in the newly created Wisconsin Territory. On June 12, 1838, land west of the Mississippi River was officially organized as the Territory of Iowa. This territory was much larger than today’s state, including present-day Iowa, most of Minnesota, and large portions of North and South Dakota. Burlington served as the first territorial capital until 1841, when the capital moved to Iowa City.

Territorial leaders proposed statehood as early as 1839, but many settlers opposed it. Statehood would require taxes to pay government officials, and many Iowans preferred lower costs and fewer regulations. A constitutional convention held in 1844 failed, largely due to disagreements over Iowa’s boundaries. A second convention in 1846 succeeded, setting the borders that remain today.

That same year, Iowans approved a state constitution. President James K. Polk signed the bill admitting Iowa to the Union on December 28, 1846. Iowa later adopted its current constitution in 1857, which continues to guide state government.

As Iowa grew, transportation and industry played key roles in its development. In the early 1900s, expanding railroad networks connected Iowa’s farms and factories to national markets. Hydroelectric power also became important. In 1913, the Keokuk Dam on the Mississippi River began generating electricity, supplying power to Iowa industries and cities as far away as St. Louis.

For much of its early history, Iowa was primarily an agricultural state. Most residents were farmers, and the state became known for producing corn, pork, and other crops. After World War I, falling crop prices and high land costs caused many farmers to lose their land. In response, farmers formed cooperatives during the 1930s, gaining greater economic strength by working together. World War II brought renewed demand for food, and Iowa agriculture prospered once again.

After 1945, Iowa’s economy began to change. New industries—including food processing, metal fabrication, and machinery manufacturing—expanded across the state. At the same time, improved farm equipment reduced the number of people needed to work the land. These changes shifted Iowa from a purely agricultural economy to a more industrial and diversified one.

Today, Iowa blends its farming heritage with modern innovation. Agriculture remains central, but the state is also a leader in renewable energy, especially wind power. Manufacturing, insurance, and healthcare also play major roles in the economy.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

An incomplete history. The original native people living there and displaced, what happened to them, later? They didn’t just poof into thin air!

There is so much to talk about and giving us brief information enlighten me and hope the majority of people. Thanks for taking the time to make every effort to do your best. Thanks

Great observation. This is the part of history that somehow disappears in the retelling of the story.