On February 1, 2003, the space shuttle Columbia broke apart during reentry, killing all seven astronauts on board. The disaster stunned the nation and forced NASA to confront hard truths about risk, decision-making, and the future of human spaceflight.

The roots of Columbia reach back to the early 1970s, when NASA began designing a reusable spacecraft. Unlike earlier capsules, this new vehicle would launch vertically like a rocket and land horizontally like an airplane. The program aimed to reduce costs and increase access to space. The result was the Space Shuttle, a complex system made up of an orbiter, solid rocket boosters, and a large external fuel tank.

Columbia was the first shuttle to fly. It launched on April 12, 1981, exactly twenty years after the first human spaceflight by Yuri Gagarin. Commanded by John Young and piloted by Robert Crippen, the mission proved that a reusable, winged spacecraft could survive launch and reentry. Columbia was also the heaviest shuttle, built with extra structural reinforcement. That strength made it valuable for early test flights but less flexible than later orbiters.

NASA expected each shuttle to fly more than 100 missions. While that goal proved unrealistic, Columbia still had a long career. Over 22 years, it flew 27 missions and carried 160 different astronauts, some more than once. Its flights included major milestones. It carried the first four-person shuttle crew. It deployed the first commercial satellite from a shuttle. It later flew with six- and seven-person crews. It also hosted Spacelab, a pressurized laboratory used for science experiments in orbit.

Despite these successes, the shuttle system had known weaknesses. One major concern involved foam insulation on the external fuel tank. Pieces of foam had broken off during earlier launches and struck shuttle wings or heat tiles. Engineers documented the problem, but since no shuttle had been lost because of foam strikes, the risk became normalized.

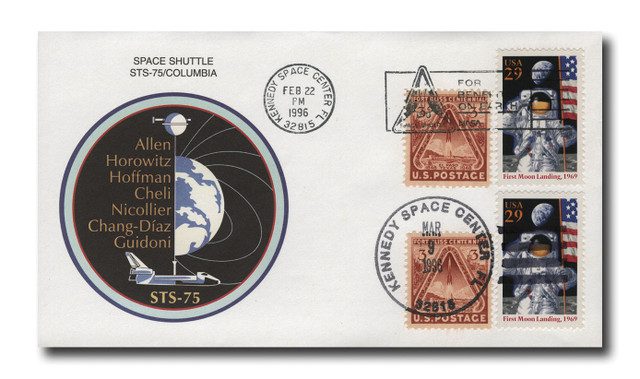

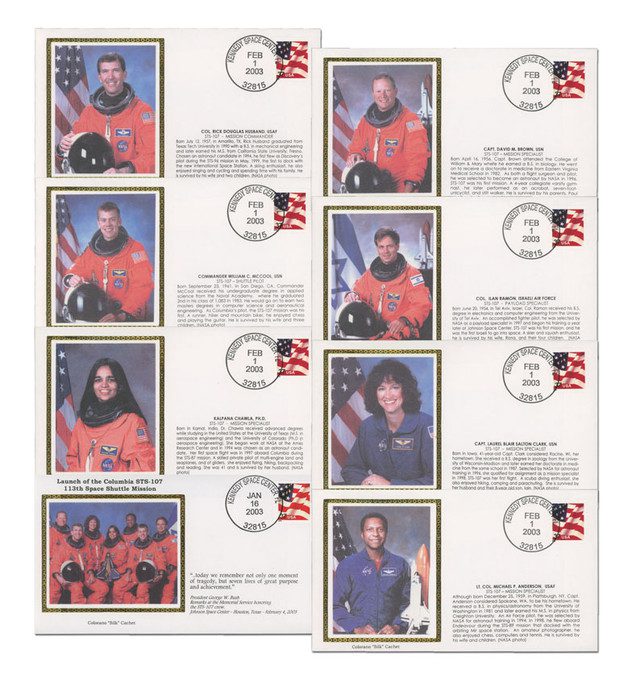

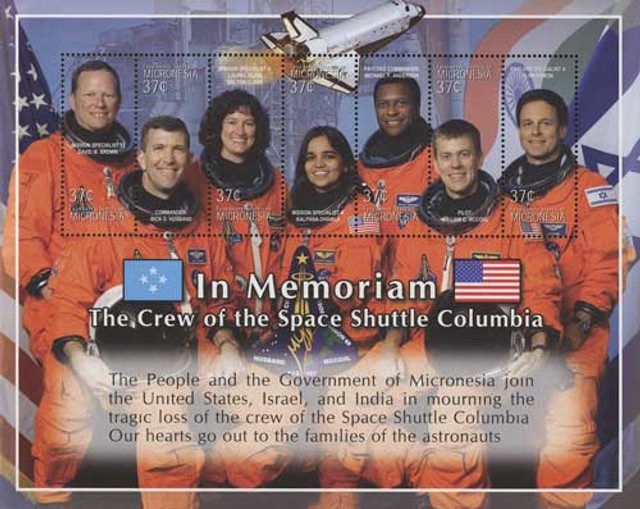

On January 16, 2003, Columbia launched on mission STS-107 from Kennedy Space Center. The seven-member crew included commander Rick Husband, pilot William McCool, and mission specialists Michael Anderson, Kalpana Chawla, David Brown, Laurel Clark, and Israeli astronaut Ilan Ramon. The mission focused on scientific research. The crew conducted more than 80 experiments, many requiring continuous work in microgravity.

About 82 seconds after liftoff, a large piece of foam broke free from the external tank. It struck the leading edge of Columbia’s left wing at high speed. Some engineers suspected serious damage. They requested high-resolution images from military satellites to inspect the wing. Management denied the requests, believing the foam strike posed no threat and that nothing could be done even if damage existed.

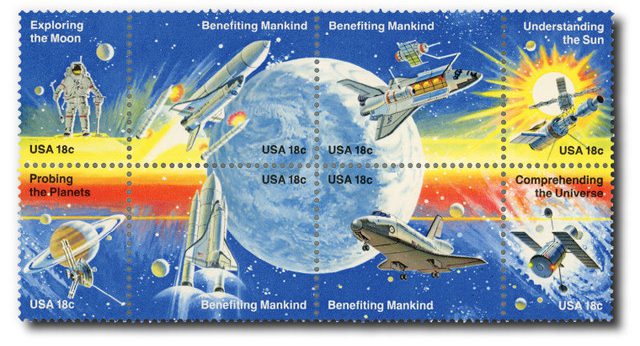

These two stamps have hidden text with the names of US shuttles, including Columbia, that can only be seen with the use of a special USPS decoder. Click here to get your decoder – there are lots more stamps with hidden images it will reveal!

The mission continued for 16 days. The crew remained unaware of the danger. On the morning of February 1, 2003, Columbia began reentering Earth’s atmosphere. As the shuttle descended, superheated air entered a hole in the damaged wing. Internal sensors began failing. At 8:53 a.m. Eastern Time, mission control noticed unusual temperature readings. At 8:59 a.m., contact with the crew was lost. One minute later, Columbia broke apart over Texas.

Debris rained down across Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana. Residents reported sonic booms and streaks of smoke across the sky. Recovery teams searched for months, collecting thousands of pieces of the shuttle. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board later concluded that the foam strike caused the disaster. It also cited deeper problems, including poor communication, flawed safety culture, and ignored warnings.

The crew was honored with memorials across the country. A permanent memorial stands at Arlington National Cemetery. NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe called the astronauts “heroes for our time and all times.” President George W. Bush urged the nation to honor them with a “living memorial” by recommitting to space exploration.

The loss of Columbia grounded the shuttle fleet for more than two years. When flights resumed, safety procedures were stricter. Yet the tragedy ultimately led to the shuttle program’s retirement.

Click here to watch the Columbia‘s final launch.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

Very interesting but I am totally surprised that only one stamp was issued in the honor of our astronauts.

I grew up in the Buck Rogers era. When the first man in space was televised, it was unreal. After 21 years flying jets in the Air Force, space flight seemed somewhat routine. I retired in TX. I remember seeing a plasma trail across the sky to the north on one early evening landing. It was surreal. When the reentry of Columbia was announced on that fateful day, I went outside and looked to the north. The image and view was not the same. That moment will be ingrained in my memory forever.

I think we should have continued the space shuttle program until a replacement could have been developed instead of paying the Russians a fortune to get back and forth to the International Space Station.

The courage of our astronauts is unquestionable. The conditioning both mental and physical is exhaustive and is indicative by the fact that there are so many who aspire but do not make the cut ,particularly here in Florida. Competition is fierce in spite of the dangers that have always existed. I remember the quote from the movie “The Right Stuff” from a skeptic during the Project Mercury years that they (astronauts) aren’t doing anything that a monkey couldn’t do. The response from the Chuck Yeager character was, “The monkey doesn’t realize he is sitting on top of a bomb.

Good article, we need To honor these brave souls went to space and back again, God bless them

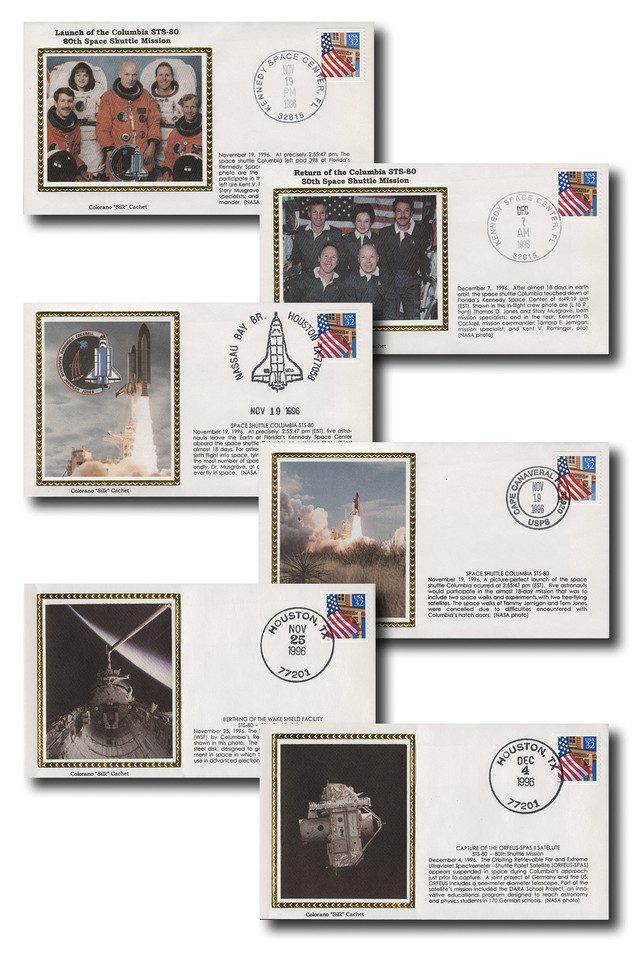

I am a space buff and collector of space stamps and coins. I followed the missions on tv and actually got to see a shuttle go up from the backyard of a friend’s home in Kissimmee and it was awesome. It was a great moment in history and, I agree, the astronauts show be honored for what they did.

Also named after the Command Module of Apollo 11, the first manned landing on a celestial body. Columbia was also the female symbol of the United States.

One big correction to the article. Columbia did NOT fly to the International Space Station. All experiments were conducted aboard Columbia in experiment modules inside the Payload bay. Since Columbia was flying independent and there was no remote arm to inspect the shuttle, the breach in the wing was not located on camera. Had the Columbia been at the ISS, the breach would have been discovered and the astronauts could have been rescued.