On February 22, 1855, Governor James Pollock put his signature on a document that changed Pennsylvania’s future. It created The Farmers’ High School of Pennsylvania — the seed of what would eventually become Penn State — and set in motion a struggle to fulfill the promise of the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862.

Centre County was chosen as the site after James Irvin of Bellefonte donated 200 acres of land and sold the trustees 200 more. The mission was practical: teach the sons of Pennsylvania farmers to apply scientific principles to agriculture. Tuition, room, and board came to $100 per year — roughly one-third of what most colleges charged. The first class of 69 students arrived on February 16, 1859.

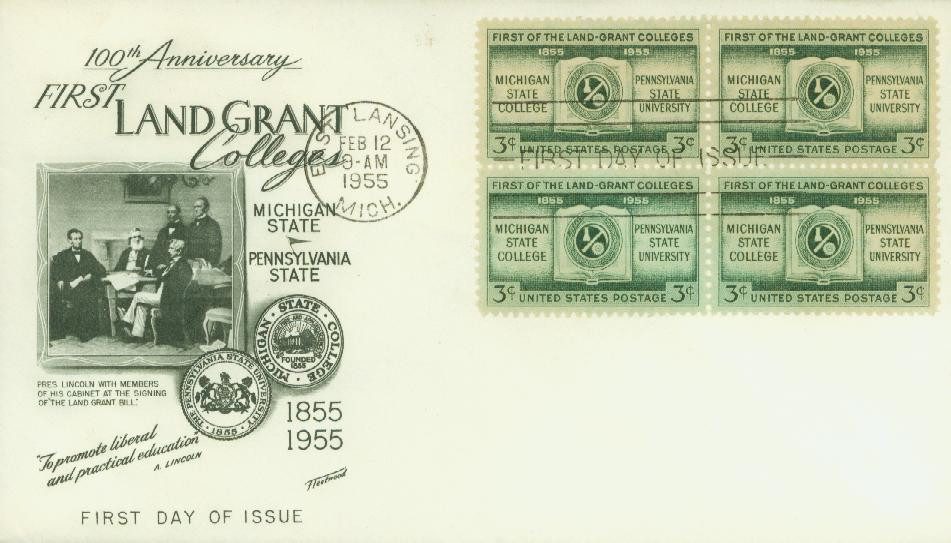

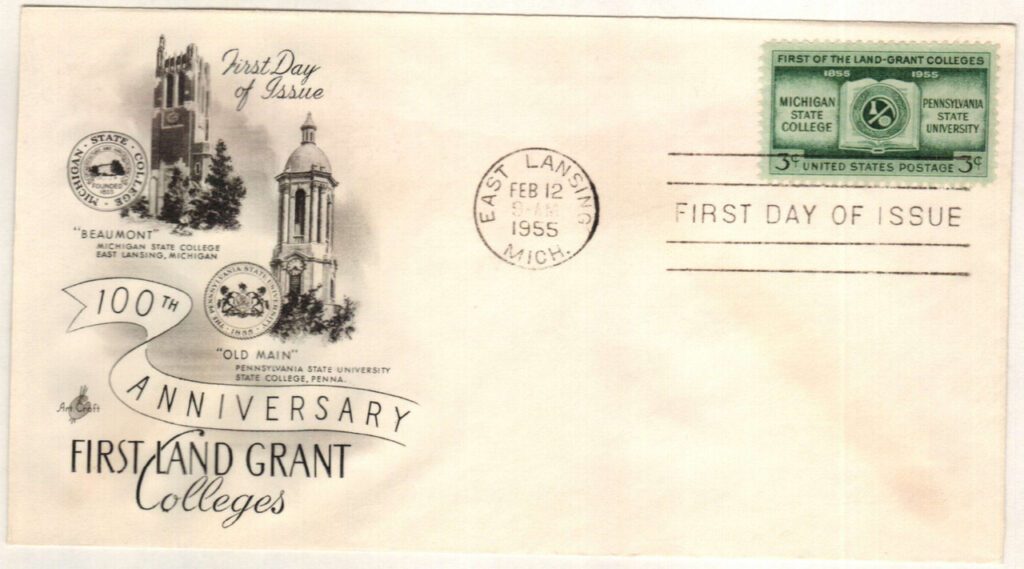

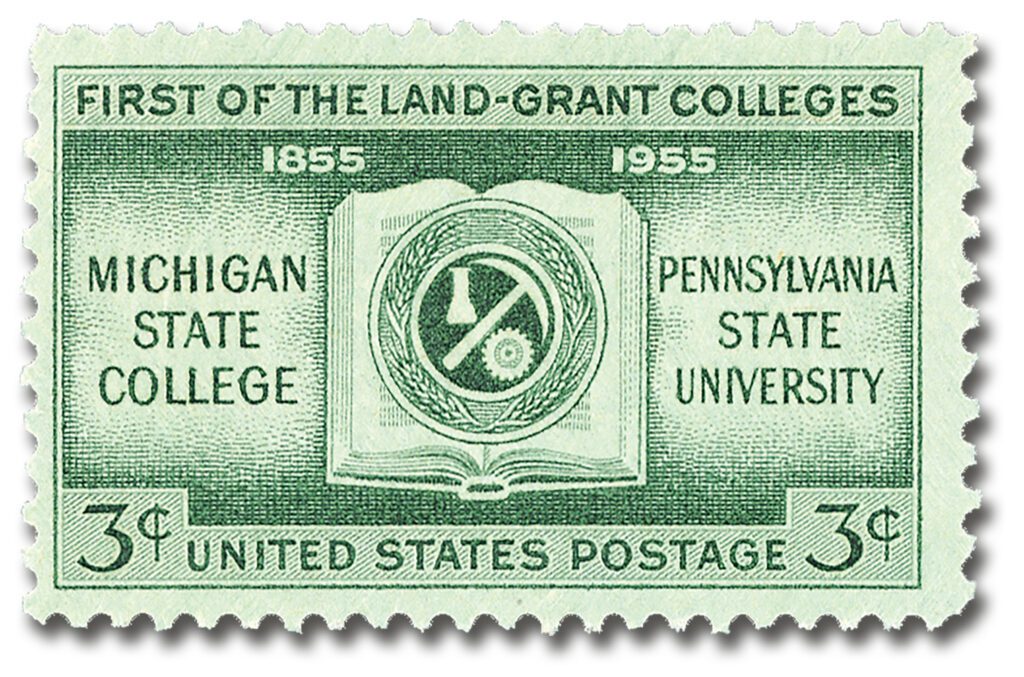

But the institution nearly died in its first decade. Finances were precarious. Enrollment was unstable. Politicians in Harrisburg doubted whether it was worth funding at all. The passage of the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862 should have been the school’s salvation. Signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 2, 1862, the act gave each state 30,000 acres of federal land for every senator and representative in Congress. States sold that land and invested the proceeds. The interest funded colleges where “the leading object shall be… to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts.”

Pennsylvania had two senators and 24 representatives. That entitled the state to 780,000 acres — most of it in far-off western territories. The school’s president, Evan Pugh, had lobbied fiercely for the designation. In 1862, Pugh even renamed the institution the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania to better align with the act’s language.

Governor Andrew Curtin — a Bellefonte resident and trustee of the college — designated it as Pennsylvania’s sole land-grant beneficiary in April 1863. But the money came slowly and unevenly. Pennsylvania sold its land scrip at an average of only 56 cents per acre — well below the federal benchmark of $1.25. Total proceeds came to roughly $439,186.80. The endowment income it generated was far too small to sustain a growing institution.

After Pugh’s death in 1864, the college entered what historians call an eighteen-year decline. Five presidents came and went. The name changed again — to the Pennsylvania State College — in 1874. By 1875, enrollment had fallen to just 64 undergraduates. By 1882–83, the entire student body numbered only 23. The Pennsylvania legislature was skeptical. State appropriations dried up. The school limped along on land-grant endowment income alone.

On June 22, 1882, the board of trustees unanimously elected George Washington Atherton as the college’s seventh president. He was 45 years old, a Yale graduate, a Civil War captain, and the former Vorhees Professor of History, Political Economy, and Constitutional Law at Rutgers College. He arrived with clear eyes. “I understand full well that my path is not to be strewn with roses,” he wrote to the board.

By 1885, Atherton’s reforms were taking shape. He had already fended off Governor Robert Pattison’s 1884 proposal to convert the college into a purely agricultural school — a plan the trustees rejected outright. Now Atherton was pushing in the opposite direction.

Pennsylvania was the most industrialized state in the nation. Its economy ran on iron, steel, coal, and railroads — not just farms. Atherton argued that the Morrill Act’s mandate to teach “the mechanic arts” demanded a robust engineering curriculum, not an institution focused solely on agricultural studies. He commissioned instructor Louis E. Reber to survey mechanical arts programs at leading institutions and rebuild Penn State’s. Workshop buildings were equipped with carpentry and metalworking equipment — much of it donated by local industry. A baccalaureate program in civil engineering was established. A two-year course in mechanic arts followed.

In May 1887, the Pennsylvania General Assembly granted Penn State its first appropriation in nearly a decade: $100,000 for new construction. That money helped launch an agricultural experiment station and new classroom buildings. By 1893, 128 of the college’s 181 undergraduates — 71 percent — were enrolled in engineering disciplines. By 1900, Penn State’s engineering program ranked tenth in the country by enrollment. The graduating class of seven in 1882 had grown to 86 by the time Atherton died in 1906.

In 1895, Atherton reorganized the college into seven distinct schools: Agriculture; Engineering; History, Political Science and Philosophy; Language and Literature; Mathematics and Physics; Mines; and Natural Science. It was the structural foundation of a modern university. Today, Penn State enrolls more than 89,000 students across 24 campuses.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.