Anthropologist Ruth Fulton Benedict was born on June 5, 1887, in New York City, New York. Benedict’s father died when she was very young and her mother was grief stricken over it for the rest of her life. These experiences instilled in Benedict an interest in grief and how it was processed by different cultures.

Benedict went on to attend Vassar College where she found writing as a great way to express herself as an “intellectual radical,” as her classmates called her. She graduated in 1909 with a degree in English Literature and then went on a one-year tour of Europe. After returning, Benedict worked a variety of jobs, including social work and teaching. It was while she was teaching in California that she developed an interest in Asia that would later lead her to find anthropology. In the meantime, Benedict returned to her family’s farm back east to find peace and meaning, as she had been unhappy with her jobs up to this point. During this time that she met and fell in love with Stanley Benedict. She began writing again and had some of her poems published under pseudonyms. Benedict then began attending the New School for Social Research in search of a new career. It was here that she really became interested in anthropology. She then transferred to Columbia, where she earned her PhD in anthropology in 1923. She began teaching the year before and among her students was Margaret Mead, who became her close friend. In 1931, Benedict was made assistant professor in Anthropology.

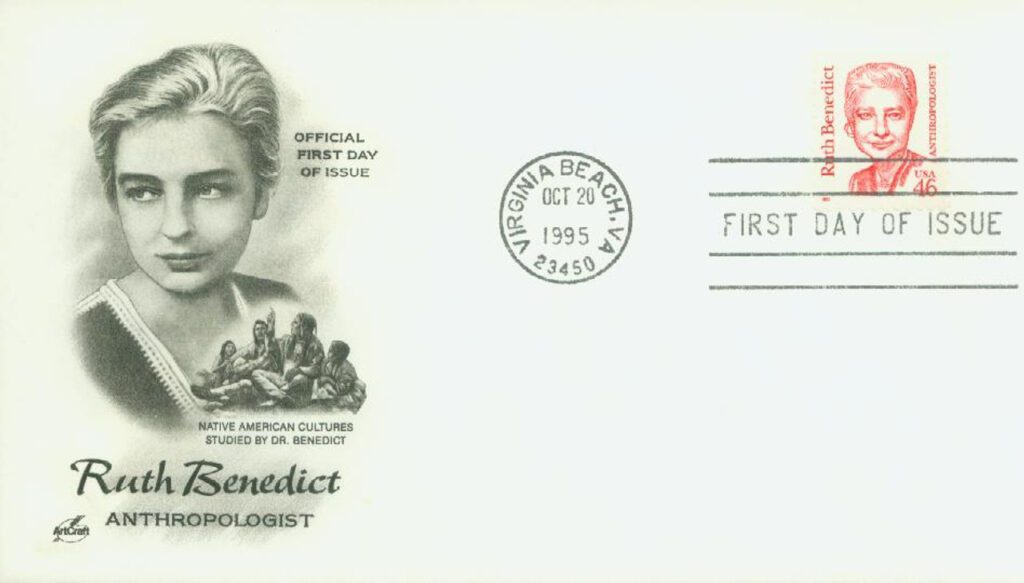

Benedict wrote a number of books and papers over the years, one of the most notable being Patterns of Culture. In that, Benedict theorized that a small part of the range of possible human behavior is included in accepted forms of any given society. That cultural “personality” is then encouraged in its individuals. Benedict’s work spawned the “modal personality” of cultural behavior, which explains behavior based on a cluster of traits most commonly observed in the people of a given culture.

Recruited by the federal government for war-related research during World War II, Benedict was assigned two significant tasks. Her plainly written pamphlet, “Races of Mankind,” presented the scientific case against commonly held racist beliefs. Intended for distribution to American troops, the pamphlet debunked myths regarding racial differences in blood type, brain size, and intelligence. Benedict also analyzed the behavior of the Japanese emperor and his significance in the willingness of the Japanese people to proceed at any costs against the Allied nations. Benedict advised President Franklin D. Roosevelt that the emperor must be allowed to remain as part of an eventual surrender offer.

Benedict was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1947 and was finally made a full professor in 1948, however she died two months later on September 17, 1948. The American Anthropology Association now awards an annual prize named in her honor.

FREE printable This Day in History album pages |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.