Stories of World Famous Stamps

British Guiana 1¢ Magenta

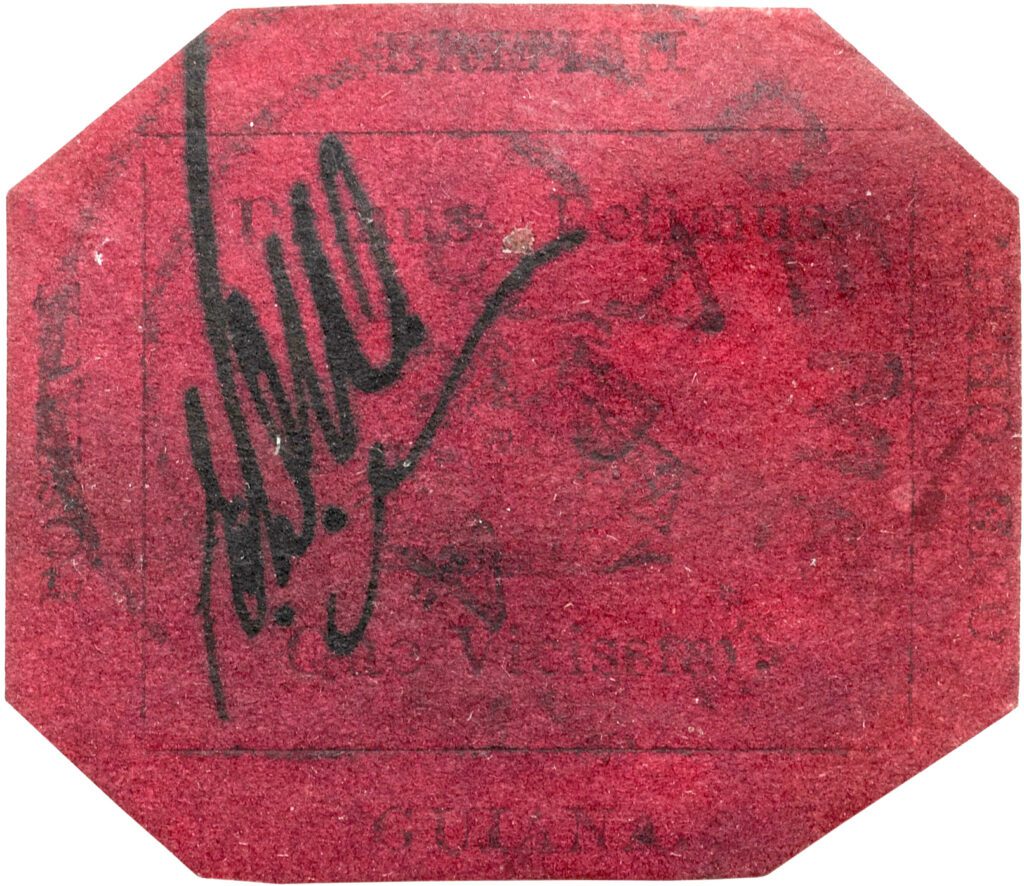

In 1873, a Scottish schoolboy discovered an unusual stamp while sorting through his uncle’s letters. Although he was a budding collector, 12-year-old Vernon Vaughn was unaware that he was holding the world’s rarest stamp.

It isn’t surprising that Vernon didn’t recognize the stamp. The British Guiana 1¢ Magenta wasn’t listed in 19th-century stamp catalogs. In addition, its corners had been cut off to form an octagon and the stamp was in generally poor condition. Vernon soaked the stamp off its envelope and placed it in his stamp album.

A short time later, Vernon sold his stamp to a local dealer in order to raise money to buy more foreign stamps for his collection. Also unaware of its rarity, the dealer paid just six shillings for the unusual stamp. Years went by and the stamp dealer sold his entire collection to Wylie Hill of Glascow, Scotland. While studying Hill’s collection, London stamp dealer Edward Pemberton

realized the magenta stamp was a one-of-a-kind rarity.

During its colonial era, the country of British Guiana (present-day Guyana) received its postage stamps from England. In 1856, supplies ran out before a fresh shipment of stamps arrived. The postmaster of British Guiana authorized an emergency issue with 1¢ and 4¢ denominations. The printer reproduced the basic design elements of the current stamps and added the image of a ship. To guard against clever forgeries, the postmaster ordered postal clerks to hand cancel each stamp with their signature. The British Guiana 1¢ Magenta paid the newspaper rate in effect in 1856 and bears the initials “E.D.W.”

The British Guiana 1¢ Magenta has been sought by some of the world’s most famous stamp collectors. Count Philippe la Renotière von Ferrary paid a sum equal to $85,000 for the rarity in the 1880s and bequeathed it to a Berlin museum. Ferrary’s collection was seized and auctioned to repay war debts following World War I. Bidding against three kings, including King George V of England, Arthur Hind purchased the 1¢ Magenta for the equivalent of $1.5 million in 1922. At the time, it was a record sale price for a postage stamp.

John E. DuPont, heir to a vast fortune, purchased the 1¢ Magenta for $935,000 in 1980. DuPont died in 2010 while serving a prison sentence. In 2014 the British Guiana was sold at auction to American shoe designer Stuart Weitzman for over $9,480,000.

24¢ Jenny Invert

Familiar with the potential for errors associated with bi-color printing, collector William Robey was stunned at his good fortune when a postal clerk sold him a sheet of 100 inverted 24¢ airmail stamps. The date was May 14, 1918, and one of the most colorful stories in philately was about to unfold.

World War I was raging when Postmaster General Burleson suddenly announced that airmail service would begin on May 15, 1918, between New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC. Already understaffed and overworked producing war bonds and revenue stamps, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing rushed to print the first US airmail stamps.

A patriotic design featuring the Curtiss JN-4 airplane in red, white, and blue was chosen to lift war-weary spirits. Printing the stamp in two colors required workers to pass the stamp sheet through the printing press twice. Nine sheets were fed through the press backwards. A single error sheet made its way to a Washington, DC, post office. Robey purchased the sheet for $24.00, more than $1,169 in today’s wages.

Word of Robey’s good luck spread rapidly. Employees immediately located and destroyed eight remaining error sheets in the Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s inventory. Many collectors assumed incorrectly that the stamps had been printed in traditional sheets of 400. That scenario left three panes of 100 unaccounted for, and both collectors and government officials went on a fruitless scavenger hunt in search of the missing inverted stamps.

Robey sold his sheet of inverted stamps to Eugene Klein for $15,000, a 62,400% profit. Klein re-sold the sheet to eccentric multi-millionaire Colonel Edward H.R. Green for $20,000, a figure equal to almost $975,000 today. Acting on Green’s behalf, Klein numbered each stamp in pencil, broke the sheet up and sold several single stamps. Colonel Green kept the unique Jenny Invert Plate Block for his personal stamp collection until his death in 1936.

The Jenny Invert Plate Block circulated among philately’s elite for decades. Several record sale prices, culminating with a $2.97-million sale in 2005, reflect its status as the world’s greatest stamp rarity.

The Jenny Invert Plate Block made headlines again in 2005. Don Sundman, president of Mystic Stamp Company, traded his rare 1868 1¢ Z Grill stamp for the one-of-a-kind Jenny Invert Plate Block. With a combined value of $6 million, the trade is a landmark in philatelic history and another intriguing chapter in the fabulous story of the 24¢ inverted airmail stamps.

In 2014, Don Sundman sold the Jenny Invert Plate Block for over $4.8 million to Stuart Weitzman.

CIA Candleholder Invert

In 1985, news of a newly discovered US invert stamp rocked the philatelic world. It was the first major inverted stamp in 66 years and said to be rarer than the coveted Jenny inverts. But the details were cloaked in secrecy, hidden in a maze of deception that took two years to unravel.

The story began when an auctioneer specializing in US error stamps announced the discovery of 85 inverted 1979 $1 Rush Lamp stamps. The stamps had been discovered by a “business in northern Virginia” and the finder wished to remain anonymous. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing launched an internal investigation and found that there were no indications of impropriety by its employees.

A few months later, Mystic Stamp Company joined with two partners and purchased 50 of the inverts. Curious about their origin, Mystic President Don Sundman filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Months passed. When the report finally arrived, it was accompanied by a cover letter – from the Central Intelligence Agency! Names were blocked out in the 35-page report, but Sundman was able to gather enough information to trace the stamps back to the CIA.

Sundman discovered that an on-duty CIA employee had purchased the partial sheet of 95 inverted stamps at a small post office near McLean, Virginia. When he and his co-workers realized what they had, they pooled their money and substituted non-error $1 Rush Lamp stamps for the inverts. Each of the nine co-workers kept a stamp. The remaining 86 stamps, including one that was damaged, were quietly sold to the auctioneer.

The story made headlines across the nation and was featured on every major television network. The CIA launched an ethics investigation and demanded that the co-workers surrender their inverts or face 10 years in prison and a $10,000 fine for conversion of government property for personal gain. Five employees returned their stamps, one claimed his had been lost, and three people resigned. The CIA donated the recovered inverts to the National Postal Museum, where they joined a copy donated earlier by Mystic.

Investigations conducted by the Bureau of Printing and Engraving and Justice Department cleared the co-workers of any wrongdoing. Twenty years later, the employee who purchased the sheet and later claimed to have lost his copy, offered to sell the stamp to Mystic. As of this writing, these neat error stamps, bearing the words “America’s Light Fueled By Truth and Reason,” are valued at $17,850 each.