The Stickney Press: a Revolution in Stamp Production

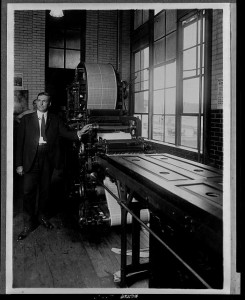

Benjamin Rollin Stickney isn’t a household name. In fact, he’s not known at all today outside of collectors and a handful of government workers. But Stickney caused a revolution in stamp production that saved the government time and money. Lots of money. Stickney was born in Port Henry, a tiny town located on the shores of Lake Champlain in New York’s Adirondack Park. While working at a machine shop in nearby Ticonderoga, he met Hattie Delano, a cousin of FDR. At the age of 26, Stickney began working as a mechanic with the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. He soon married Hattie and moved to Washington, D.C.

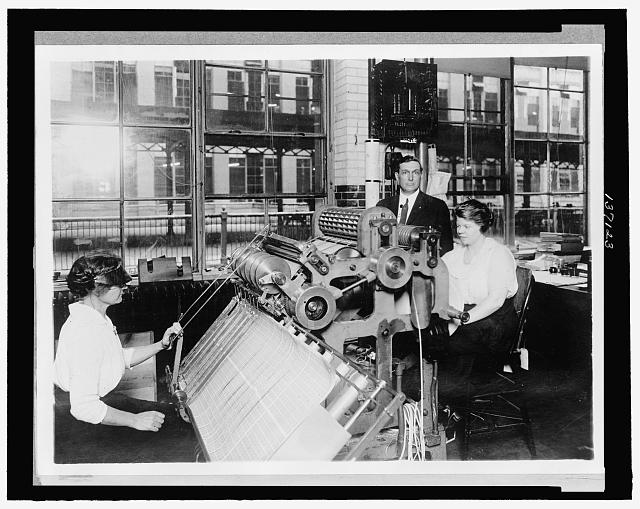

It didn’t take Stickney long to make a favorable impression at the BEP. Within 10 years, over 12 of his inventions were being used by the department. Because of his apparent talent, Stickney was given a challenge no one else had mastered. Although some of the greatest minds had tried and several hundred thousand dollars had been spent, no one had been able to develop an effective dry printing method. Stickney had an idea, but the BEP lacked the money to build a prototype. Finally, the Post Office Department helped out – and the result was amazing.

The first stamp produced on the Stickney Press

Stickney developed a system that eliminated 23 steps from the previous printing process. Using his invention, what had taken six days could now be done in just nine hours. Plus the cost savings were over 50%. The Stickney Press, which was a rotary web-fed intaglio press, allowed the BEP to print about 14 billion postage stamps a year and save millions of dollars. Additional revenue was made when several other countries purchased Stickney Presses for their own use. Ironically, Stickney – one of the most promoted government employees – was making just $3,500 per year during this time. Because his patents were done in the course of his employment, he earned nothing extra for his inventions. Stickney’s salary increased to $5,000 in the early 1920s. On March 31, 1922, he and several others were fired without warning by President Warren Harding after false accusations were made about the BEP. Nearly a year later, Harding conceded his mistake and they were all rehired. Six months later, Harding died suddenly. The Postmaster General ordered a special commemorative stamp issued to honor the fallen President. The mourning stamp was rushed into production in less than a month, and demand was strong. In a twist of irony, Stickney’s presses were used to print the stamps honoring the man who had fired him.