On the cold night of December 24, 1826, a group of cadets at the United States Military Academy at West Point launched an eggnog-fueled riot that shocked the school and embarrassed the young nation. What began as a forbidden holiday celebration quickly spiraled into violence, gunfire, and destruction. By the following morning, order was restored—but the incident, later known as the Eggnog Riot, left a lasting mark on West Point’s history.

By the early 1800s, American farming had expanded rapidly, especially dairy farming. Milk, cream, and eggs were more affordable and widely available than in earlier generations. As a result, eggnog became a popular holiday drink, especially at Christmas. At West Point, however, strict rules governed cadet behavior. Alcohol possession, drunkenness, or intoxication of any kind was forbidden and could lead to serious punishment, including expulsion. Academy officials reminded cadets of these rules as Christmas approached, making it clear that any eggnog served at official gatherings would be alcohol-free.

Not all cadets were willing to accept that restriction. In the days leading up to Christmas, a small group met secretly at a nearby tavern and planned how to smuggle alcohol into the academy. Their plan succeeded. By Christmas Eve, the cadets had brought two and a half gallons of whiskey and a gallon of rum onto campus. They also collected food from the mess hall to fuel their private celebration.

The party began quietly around 10 p.m. on December 24, with just nine cadets gathered in one room. As the night went on, more cadets joined, and a second party broke out nearby. The eggnog was heavily spiked, and spirits rose quickly. In the early hours of Christmas morning, the drunken cadets began singing loudly, shouting, and causing a disturbance. Among those disorderly cadets was a young Jefferson Davis, who would later become president of the Confederate States of America.

The noise eventually woke Captain Ethan Allen Hitchcock, a faculty member responsible for discipline. Hitchcock went to one of the rooms and ordered the cadets to stop and return to their beds. Some obeyed, but others were angry and humiliated. Rather than calming down, they began plotting retaliation against Hitchcock.

Although Hitchcock returned to bed, the disruptions continued. Repeated knocks on his door forced him to investigate again. He followed Jefferson Davis to one of the rooms and demanded to know who had supplied the alcohol. When the cadets refused to answer, Hitchcock left to seek help from another officer, Lieutenant William A. Thornton.

Thornton, who had slept through much of the night’s chaos, finally awoke after hearing shouting outside. As he stepped out to investigate, two cadets attacked him, knocking him unconscious. Unable to find Thornton, Hitchcock returned to his room—only to have it attacked by a group of drunken cadets. One even fired a pistol into Hitchcock’s room. At this point, Hitchcock opened the door and began arresting those involved.

Confusion spread as rumors flew. Some cadets believed they heard Hitchcock say he would bring in artillery soldiers, known as bombardiers, to suppress the riot. Fearing force, the rioters armed themselves to “defend” their barracks.

At 6:05 a.m., reveille sounded as usual, but it was accompanied by gunfire, shattered windows, shouting, and threats against academy officials. Cadets who had not participated were horrified by the damage and behavior of their classmates. As sobriety returned and daylight exposed the destruction, tensions quickly faded. By the end of breakfast, the mutiny was over.

Superintendent Sylvanus Thayer, who had slept through most of the riot, immediately launched an investigation. The damage was estimated at $168—more than $5,500 in today’s money. Investigators determined that about 70 cadets had taken part. Those who smuggled alcohol and led the violence were prosecuted. As required, President John Quincy Adams reviewed the sentences and made final adjustments. The case was officially closed on May 3, 1827.

The Eggnog Riot became a cautionary tale at West Point, reinforcing the importance of discipline and order.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

I have never heard about this incident. Thanks

Neither had I–very interesting, but very foolish.

Fascinating story

wow nice history of the West Point

These daily stories are great…lived much of my life across the river from USMA and never heard of this incident…thanks and keep ’em coming

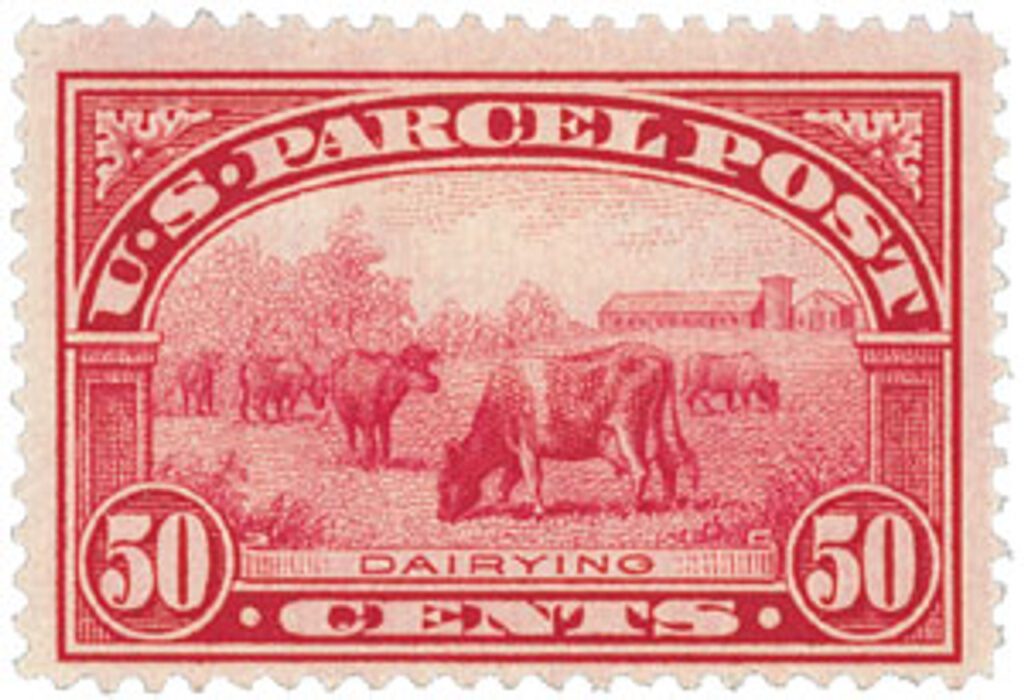

Fascinating but doesn’t state that ultimately eleven were expelled after President Adam’s review. I really appreciate Mystic’s history of stamps.

“Alcohol possession, as well as drunkenness and intoxication, at the West Point Military Academy had long been against the rules. Anyone found in violation of this rule could be expelled.”

Where is the rest of the story? I have to just wonder, was anyone expelled ?

Now there’s something you won’t read in school history textbooks. You know for an inexpensive stamp that 5cent West Point stamp is a beauty. In fact those sets of the Army and Navy are really nice. Love the engraved stamps.

As to why there is no longer any daily RUM ration in the USN Will Provide for better entertaining reading

The Royal Navy used rum in their grog. The US Navy used rye whiskey, since there was no place in the US to grow sugar cane for rum. We have plenty of rye, however. The grog ration ended on 1 September 1862.

I never knew of this incident. Thanks for letting us in on it, Mystic. Happy Holidays!

Had never heard this either really enjoy these little stories

An interesting story – but would the stamp be better served with the real history of West Point. It likely already is part of these wonderful histories so a reference to it here is appropriate I think

The real history is not whitewashed. Thanks for sharing this ancedote in the lives of these young men.

Great story, very interesting. Thank you !