On May 10, 1876, the first official World’s Fair in the United States was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The fair also commemorated the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Prior to this, the US had staged the Great Central Fair of 1864, one of several sanitary fairs held during the Civil War. This and similar fairs showed how public, private, and commercial efforts could join together for a larger fair. The 1864 fair included handmade and industrial exhibits plus a visit from the president and his family and offered ordinary citizens the chance to support the welfare of the brave Union soldiers and join in the war effort.

Two years after that fair, John L. Campbell, a professor at Wabash College, first suggested a world’s fair in Philadelphia to mark America’s centennial. Initially, many people thought it was a bad idea. They believed that they wouldn’t be able to find funding and that America’s exhibits might not measure up to those of foreign nations. With support from the Franklin Institute, though, the fair was approved in January 1870.

Funding came from several sources – the city, the state, and extensive fund raising. New hotels were built and transportation was improved to bring people into and around Philadelphia. The 115-acre fairgrounds housed more than 200 buildings. These included five main buildings as well as separate structures for state, federal, foreign, corporate, and public exhibits. This was an unusual strategy compared to past fairs that usually only had one or a few large buildings.

The fair’s official name was “The International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine,” but it was more commonly known as the Centennial Exhibition. It was originally supposed to open in April, to honor the battle of Lexington and Concord, but it had to be delayed due to construction issues. The fair finally opened on May 10, 1876, with the ringing of bells throughout Philadelphia. President Ulysses S. Grant, Emperor Pedro II of Brazil and their wives participated in the opening ceremonies. Grant and Pedro ended the ceremony by turning on the Corliss Steam Engine that powered many of the exposition’s machines.

That first day, 186,272 people were in attendance, though 110,000 had free passes. Attendance dropped off sharply after that, and was further hurt by a heat wave in June and July. Cooling temperatures and positive reviews later created a surge in attendance.

Visitors to the fair saw a number of new inventions, including sewing machines, typewriters, stoves, air-powered tools, lanterns, guns, horse-drawn wagons, carriages, and an array of agricultural equipment. Among the most popular exhibits were the world’s first monorail system and a portion of the Statue of Liberty (its arm and torch). Visitors could pay 50¢ to climb a ladder to the top of the torch. These funds were used to help pay for the statue’s pedestal. Additionally, Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone was set up at opposite ends of one hall to show how voice could travel over wires. And Thomas Edison displayed his automatic telegraph system and electric pen. Visitors were also introduced to some new foods, including bananas, popcorn, and Heinz ketchup.

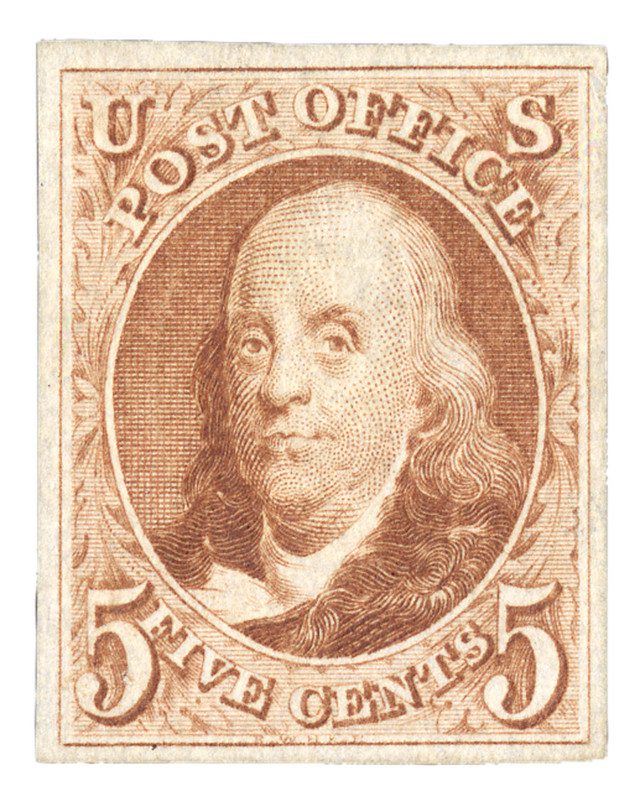

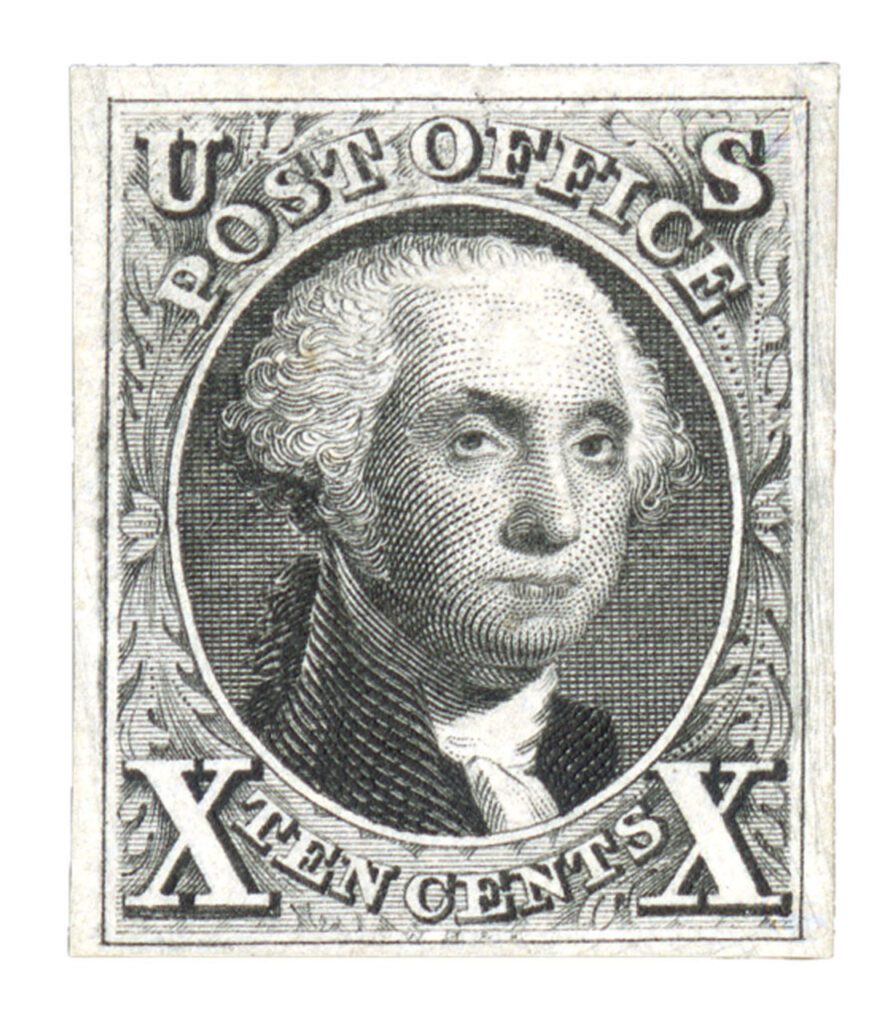

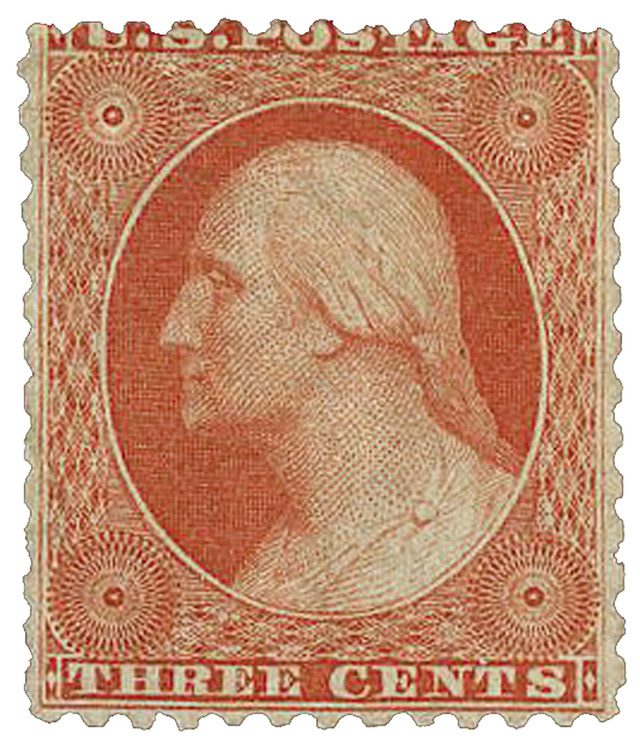

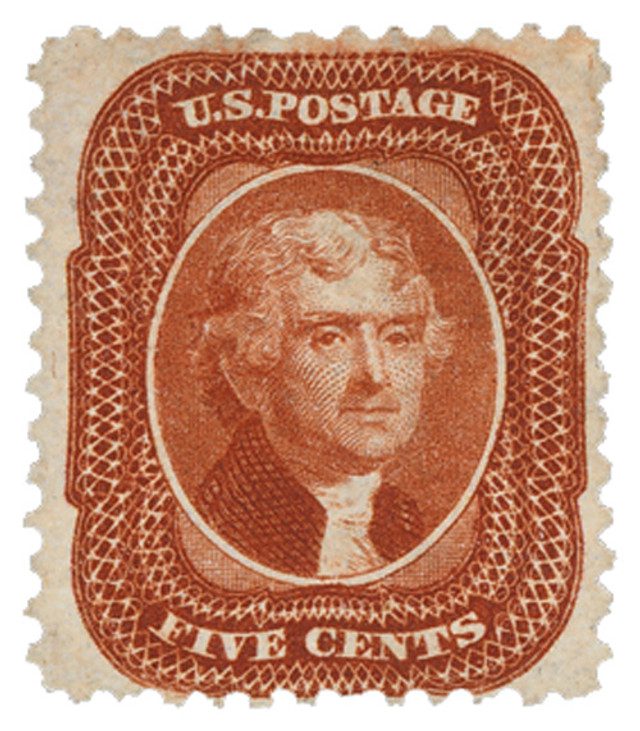

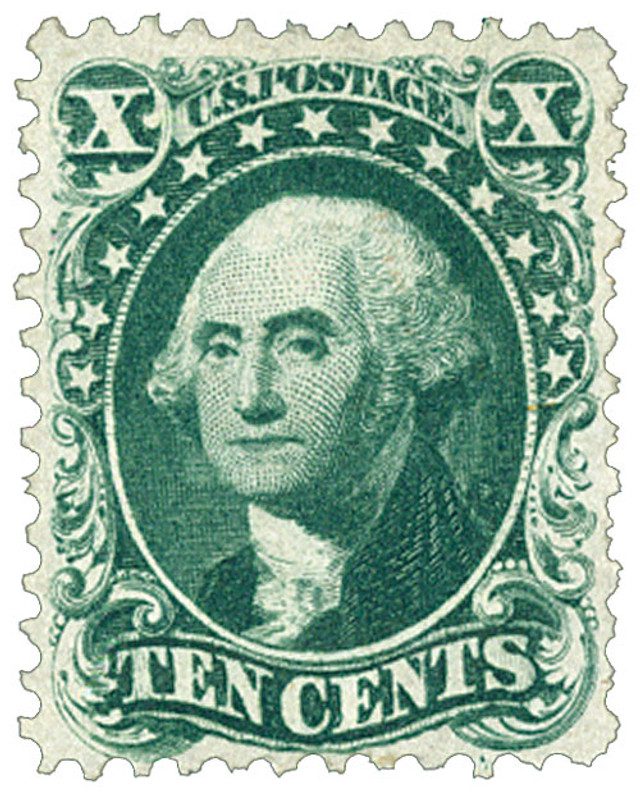

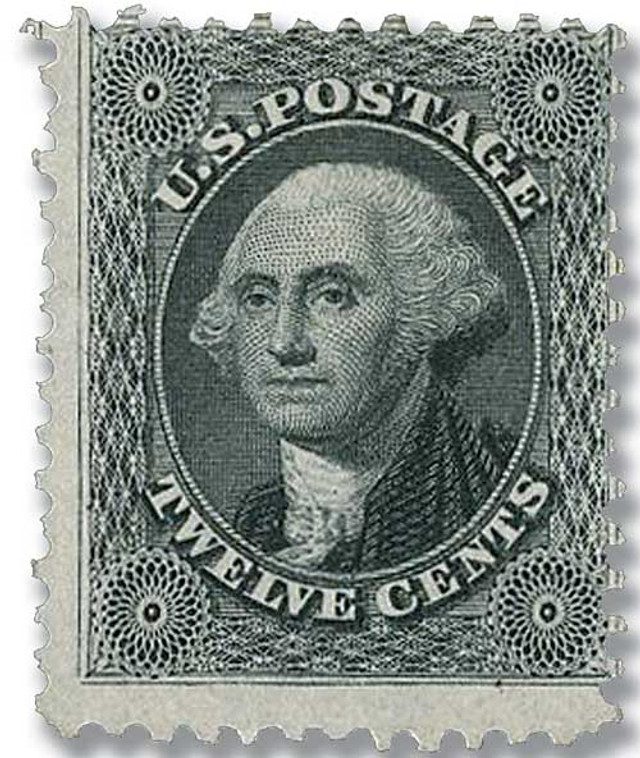

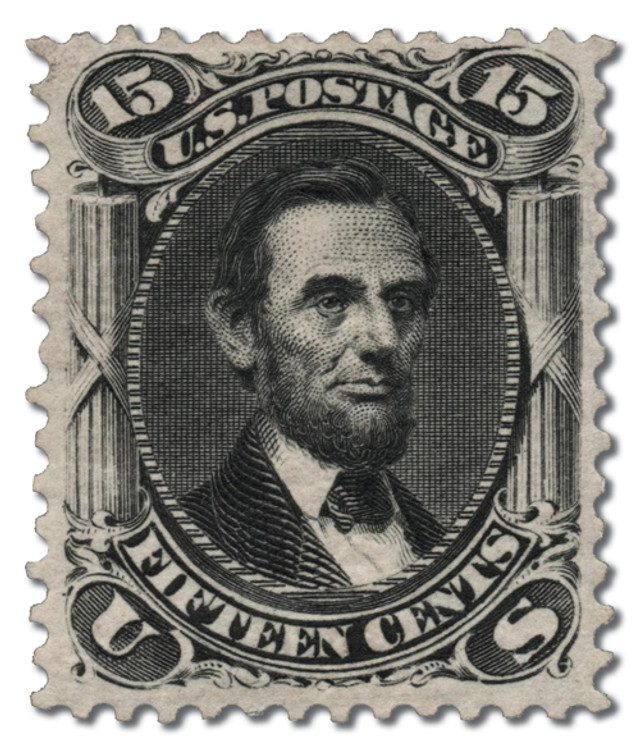

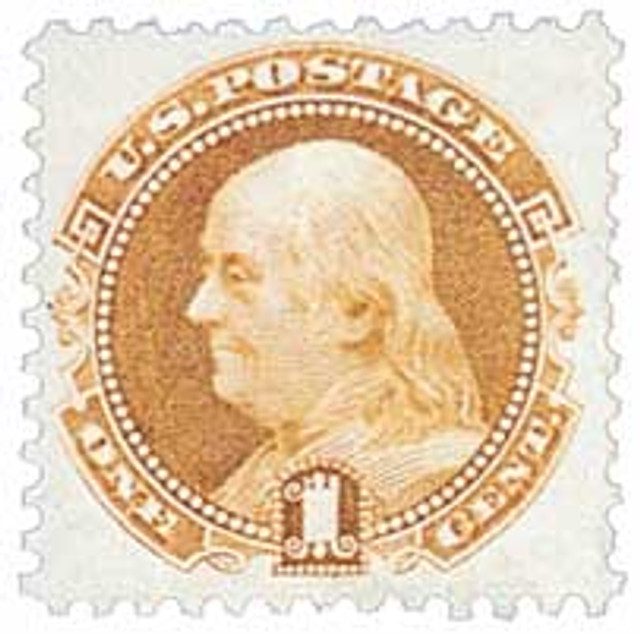

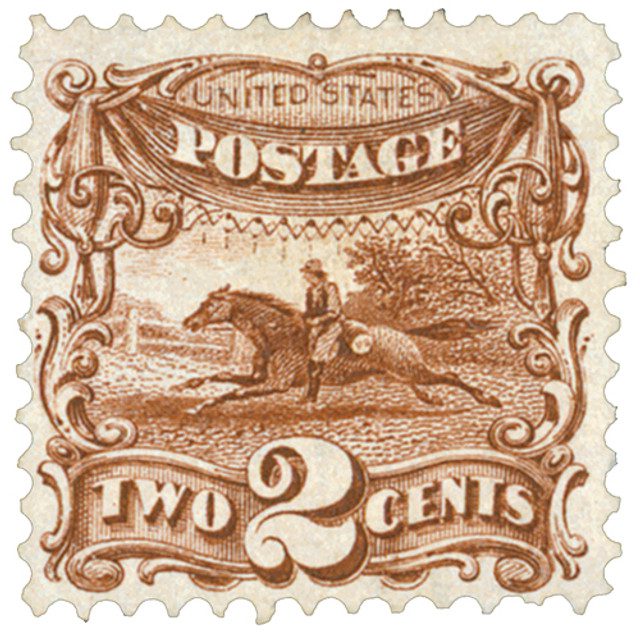

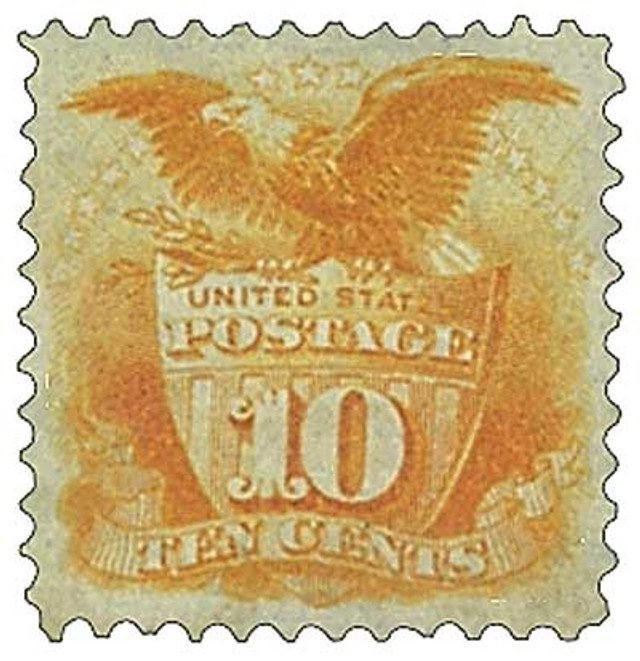

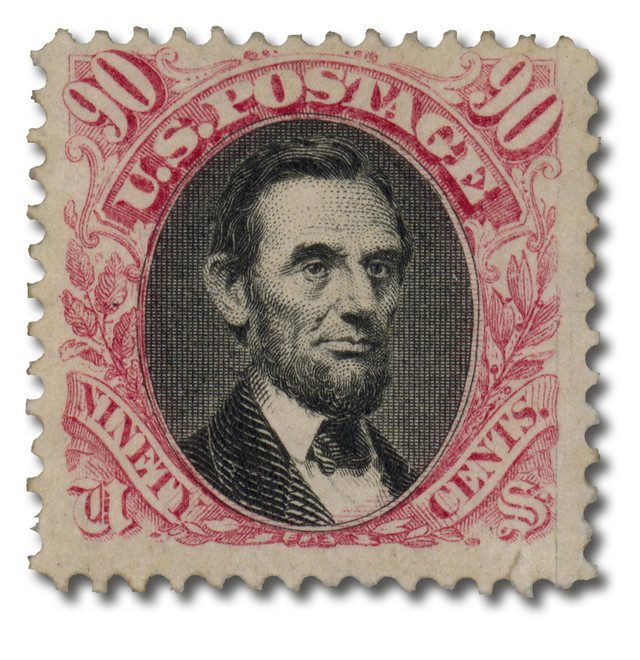

The US Post Office Department also had a strong presence at the fair. They wanted to sell every US stamp at the exhibition, even those that were no longer in use. Because many of the original plates couldn’t be found, new ones had to be engraved. Observant collectors noticed subtle differences, so Scott gave them their own numbers. Not realizing they had created philatelic rarities, the Post Office Department sold them as planned. Most of these stamps weren’t valid for postage and were issued in very small quantities. And most of the unsold stamps were later destroyed!

While the fair didn’t turn a significant profit, 10 million people attended it. Additionally, it showed other nations how much America had grown industrially and commercially and helped to increase trade.

See below for more of the stamps issued at the exhibition. They were all produced in limited quantities!

Click here for images and more from the exhibition.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

Wonderful article on this centennial international exhibition. I liked the additional pictures of the Exhibition buildings.

The fair improved trade in 1876; what are we doing in 2025?