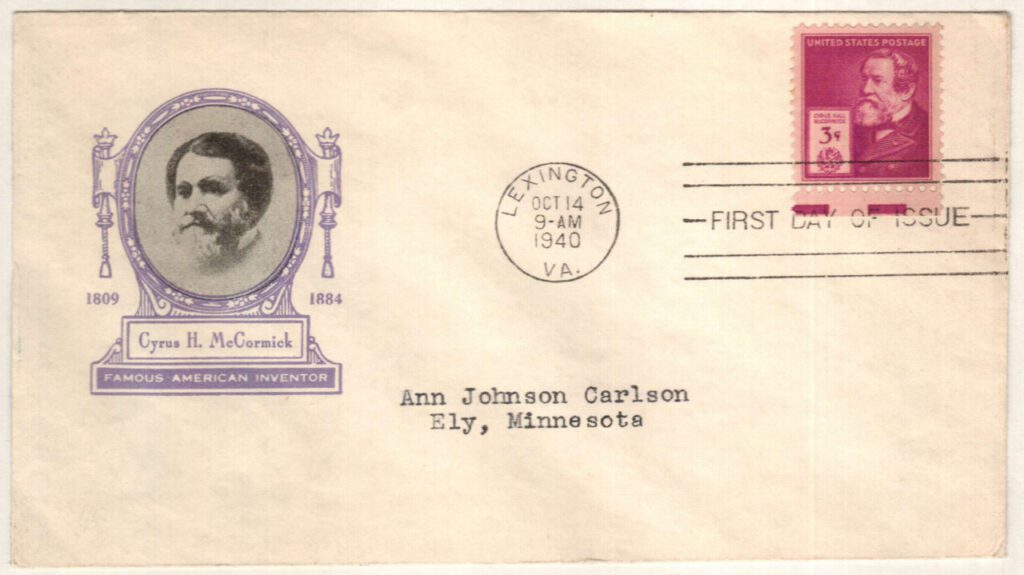

Inventor and businessman Cyrus McCormick died on May 13, 1884, in Chicago, Illinois.

Cyrus Hall McCormick was born on February 15, 1809, in the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia. He was the oldest of eight children born to inventor Robert McCormick Jr. Around the same time Cyrus was born, his father began working on a design for a mechanical reaper. He spent 28 years working on the design but never managed to make it right. So Cyrus went on to take up the project himself.

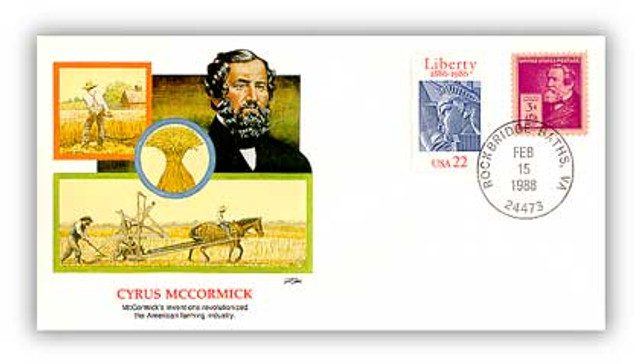

McCormick worked with Jo Anderson on the design. While some machines were designed to be pushed by horses, McCormick worked on a machine that would be pulled by horses and cut the grain on one side of the team. In 1831, McCormick held one of the first demonstrations of his new machine. He said he had developed the finalized version in 18 months. McCormick was then granted the patent for his reaper on June 21, 1834.

During this time, McCormick and his family also had a blacksmith and metal smelting business, which nearly went bankrupt during the Panic of 1837. McCormick began holding more demonstrations of his machine, but most local farmers thought it was unreliable. McCormick continued to improve on his original design and eventually began to sell more – seven in 1842, then 29 in 1843, and 50 in 1844. The following year, he got another patent for the improvements made to the reaper.

Up until this point, the machines were all built in the family farm shop. But McCormick realized that he was receiving orders for reapers from out west, where the farms were larger and flatter. McCormick contracted to have his machines mass-produced at a factory in New York. In 1847, he and his brother opened their own factory in Chicago. The business prospered after that, aided by railroads that could help deliver the machines and replacement parts much quicker than ever before.

In 1851, McCormick took his reaper to the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London. His reaper successfully harvested a field while the Hussey machine (Obed Hussey who had a competing patent claim) failed. McCormick then won a gold medal and was admitted to the Legion of Honor, but also found out he had lost a court challenge of Hussey’s patent. By 1856, McCormick’s factory was producing over 4,000 reapers per year. Then in 1871, the factory burned down during the Great Chicago Fire, but he rebuilt it and reopened in 1873.

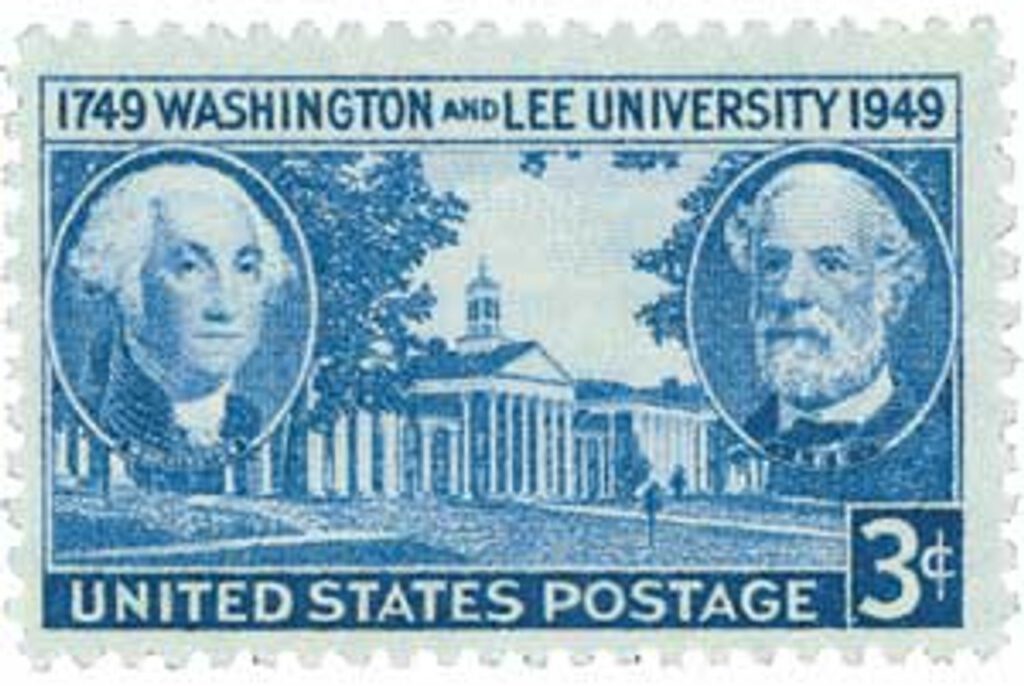

McCormick was a devout Presbyterian all his life and committed much of his time and money to helping others. He helped create the Theological Seminary of the Northwest (later named the McCormick Theological Seminary) and donated $10,000 to help start the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). McCormick and his wife also donated money to Tusculum College and helped create churches and Sunday Schools in the South after the Civil War. During the last 20 years of his life, McCormick was a benefactor and served on the board of trustees for Washington and Lee University.

After suffering a stroke in 1880, McCormick died on May 13, 1884, in his home in Chicago. He received many honors during and after his life – the French named him an Officer of the Legion of Honor and he was elected to the French Academy of Sciences for “having done more for the cause of agriculture than any other living man.” Many credit McCormick’s reaper with reducing human labor on farms, increasing productivity, and being a driving force in the industrialization of agriculture in dozens of nations.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

Great story. I enjoy reading them every day. Good to learn history.

Love the daily emails. Look forward to them even more now that we have to stay home. I’m a history buff and these stories are often about subject that I knew nothing about. Keep up the great work.

Thanks Mystic. I have to wonder if he, or his company, was the “McCormick†in Farmall McCormick and then later known as International Harvester.

These are little history lessons for me and my granddaughter. Thank you Mystic for these. They’re so interesting.