On September 11, 1935, workers broke ground on the 469-mile Blue Ridge Parkway near Cumberland Knob in North Carolina. Though it would take more than 50 years to complete, it’s been the most visited National Park Service site nearly every year since 1946, earning the nickname, “America’s Favorite Drive.”

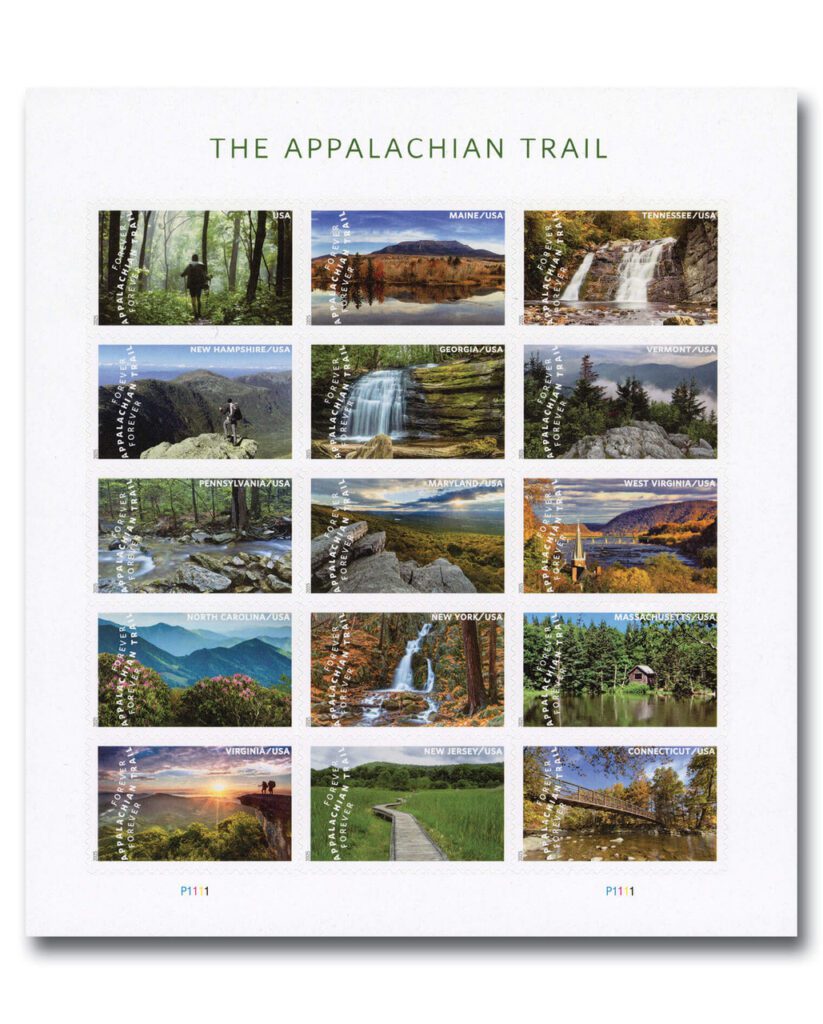

The Blue Ridge Mountains, part of the larger Appalachian Mountain Range, began forming about 350 million years ago. When the tectonic plates of Africa, Europe, and North America collided about 320 million years ago, the mountains were pushed far up above sea level, likely becoming the tallest on Earth at the time. The mountains were then subjected to millions of years of freezing, thawing, rain, snow, and wind as well as the arrival and secession of glaciers. All these elements sculpted the peaks and carved deep notches in between.

Native Americans have sporadically lived in and around the Blue Ridge Mountains for some 11,000 years. The Cherokee were the most widespread in the area and often dealt with the Piedmont in the east and Iroquois in the northwest. At some point in their history there, the Cherokee established permanent towns and grew beans, squash, and corn.

The Blue Ridge Cherokees’ first contact with Europeans came in the mid-1500s, when they adopted new technologies introduced to them. At the end of the 18th century, the Blue Ridge Mountains were home to an ever-increasing influx of Scottish, Irish, and German settlers. Between pressure from settlers and the introduction of new diseases, the Native American population in the mountains dropped dramatically. Then, in 1838, President Andrew Jackson forcibly moved the majority of the 16,000 Cherokees in North Carolina to reservations in Oklahoma in what has come to be known as the “Trail of Tears.” However, a small band of Cherokee landowners were allowed to remain and joined with others who hid or returned and established the Eastern Cherokee that still live in the area today.

By the time of the Civil War, American settlers had established small self-sufficient towns and farms throughout the Blue Ridge Mountains. But their way of life changed dramatically in the 1880s when railroads made their way into the region. They brought with them several logging operations and paying jobs.

The conservation and preservation movements of the late 1800s and early 1900s led to the creation of America’s first National Parks and National Forests – land set aside to protect natural and historic sites for future generations. Among the movement’s greatest supporters was President Franklin Roosevelt. In 1933, he visited Virginia’s recently constructed Skyline Drive, the scenic road that runs along part of the Blue Ridge Mountains and would become the backbone of Shenandoah National Park.

While on that trip Roosevelt met Virginia Senator Harry Byrd, who suggested that Shenandoah should be connected with the Great Smoky Mountains National Park that had recently been established in Tennessee and North Carolina. Roosevelt was intrigued and called a meeting with the Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee governors. Everyone was enthusiastic about the project and began putting together a planning team. Next, they proposed their idea to Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, who approved and set a budget of $16 million. Ickes then hired Stanley Abbott to serve as the new park’s architect. After visiting the area, Abbott was inspired to create a group of national parks and recreation areas that would also protect vital watersheds.

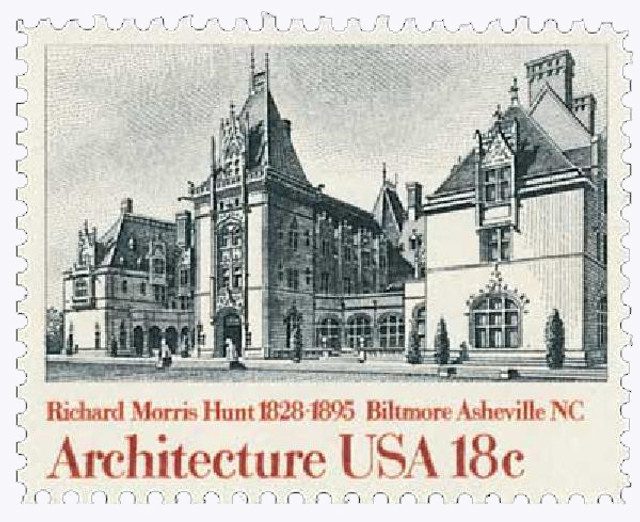

The initial suggested route was to begin in Blowing Rock, North Carolina, and run through the Unaka Mountains into Tennessee, where it would meet the Great Smoky Mountains. However, North Carolina citizens, particularly in the struggling town of Asheville, lobbied against the plan. They hoped to get the road to pass through their town and help improve the economy. Taking the fight to Washington, the Asheville group enlisted the help of North Carolina native Josephus Daniels, the US ambassador to Mexico. As it turned out, Daniels and Roosevelt had served together under President Woodrow Wilson and were good friends. Daniels convinced the president to approve the Asheville route, and construction went underway on September 11, 1935, near Cumberland Knob in North Carolina. By February of the following year, work began in Virginia. And on June 30, 1936, Congress formally authorized the Blue Ridge Parkway under the National Park Service.

While some of the construction was completed by private contractors, several of President Roosevelt’s New Deal programs were also put to use. These included the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Emergency Relief Administration (ERA), and Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). By the start of World War II, about 170 miles of the road were open to travel with another 160 miles still under construction.

The Blue Ridge Parkway was about half done by the start of the 1950s. In 1955, the National Park Service launched Mission 66, a ten-year program aimed at dramatically increasing the services provided at National Parks across the country. At Blue Ridge, the goal was to complete the road by 1966. They mostly succeeded, finishing construction on all but the last 7.7 miles at Grandfather Mountain in North Carolina. Part of the ongoing project had been negotiating the purchase or use of private lands. While some residents may have resisted, they eventually agreed to be a part of the project.

However, Grandfather Mountain owner Hugh Morton refused to agree to the construction, as he believed it would harm the area’s fragile ecosystem. Negotiations between Morton and the park service went on for years. A solution was finally reached in 1979 in the Linn Cove Viaduct, a bridge that would curve around the mountain, so as not to harm it. Both parties agreed and construction on the $10 million bridge began. The viaduct, and the Blue Ridge Parkway, were completed in 1987, making it America’s longest linear park.

Click here for more from the official National Park Service website.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.