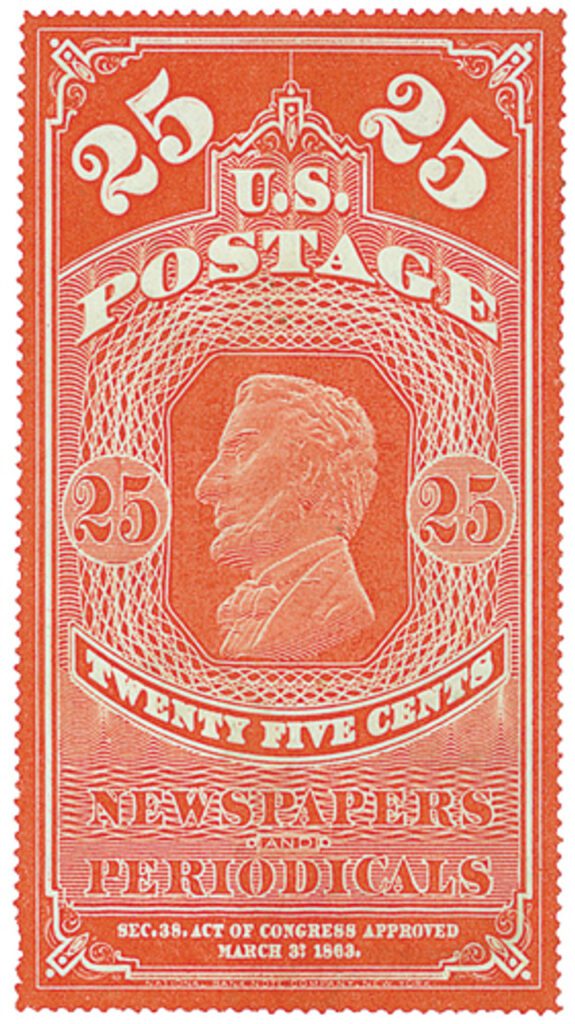

On March 3, 1863, Congress passed an act establishing three classes of mail to simplify a complicated system that included over 300 different rates.

Early American leaders believed in the importance of a well-informed public, to which the exchange of news, ideas, and opinions was essential. President George Washington supported the free press, and during his administration, the first major postal law was passed in 1792. It established low rates for newspapers at 1¢ for up to 100 miles or 1.5¢ for more than 100 miles. Meanwhile, postage for letters ranged from 6¢ to 25¢, based on the distance it was traveling. This law also permitted newspaper companies to send their papers amongst themselves for free to help spread information.

When it was suggested that the 1.5¢ rate hindered newspaper circulation, Washington ordered Congress to investigate it to see what could be done. In 1794, they lowered the rate for newspapers traveling in-state to 1¢ and gave magazines low rates of 1¢ and 2¢ based on distance traveled. The low cost of mailing newspapers helped to increase circulation, and by 1840, the US reportedly had more newspapers than any other country.

In 1845, Congress made another change, allowing newspapers to be mailed up to 30 miles for free. In 1851, weekly newspapers were allowed to be sent for free within their own county. Rates for newspapers traveling less than 1,000 miles and magazines less than 1,500 miles were lowered, and subscribers received a discount if they paid their postage quarterly. In 1852, magazines and newspapers could be mailed for ½¢ within a state and 1¢ to other states.

While prices were low, there were several variables postmasters had to consider when figuring out the postage rates for various items. Discounts for in-county and in-state newspapers, varied delivery frequencies, and publication formats added up to 300 different rates that could be used for a particular piece of mail. One article on the complex system stated, “To determine the proper charge for a paper, a magazine, or a book, postmasters are obligated to plunge into calculations of the most abstruse, and often insoluble character, the result of which, in regard to any given article, never comes out the same for two different and distant computers.”

In 1862, former newspaper editor Schuyler Colfax investigated the complexities of these rates and proposed postal reform to simplify them. He suggested the creation of three rates. The following year, Senator (and former postmaster general) Jacob Collamer and then-Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, collaborated on such a law. With their combined experience, they developed three mail classifications, which were accepted with by the House and Senate without debate and passed into law on March 3, 1863.

Under the new law, first-class mail consisted of letters, second-class was regular printed matter, and third-class was miscellaneous matter. The law defined second-class mail as “all mailable matter exclusively in print and regularly issued at stated periods, without addition by writing, mark, or sign.” Third class “embraces all other matter which is or may hereafter be by law declared mailable.” The law was also significant in that it was the first to establish a uniform postage rate on letters regardless of distance traveled. The new rates were 3¢ for letters under ½ ounce and 3¢ for each additional half-ounce.

Under the new law, periodicals cost less than ½¢ to send, unless they were published less than weekly, then the rate was 1¢. Initially this postage could be paid by the mailers or recipients. However, because postmasters found themselves unable to collect postage from some customers, prepayment by the publishers was made mandatory on January 1, 1875. This also set a new rate of 2¢ a pound for publications sent each week and 3¢ a pound for those sent less often. In 1879, as a result of calls from the publishing industry, the 2¢ per pound rate was applied to all periodicals no matter how frequent they were mailed. This rate was lowered to 1¢ in 1885.

However, over the next 30 years, second-class mail volumed increased 12-fold, while first-class mail only increased by six or seven-fold. Postal officials also realized that many people were taking advantage of the low second-class rate, by disguising books as serials and advertising circulars and magazines. Its estimated the Post Office lost up to $27 million in revenue from this misuse. Special commissions were formed to study the issue, but no action was taken until World War I. The War Revenue Act of October 3, 1917, increased second-class postage rates and periodicals were charged extra if advertisements made up more than 5% of the publication.

Second-class mail volume continued to increase over the years, yet the post Office was still losing money. In 1951, President Harry Truman argued in favor of a rate increase state that “newspaper and magazine publishers will have 100 million dollars – or 80% of their postal costs paid for them by the general public.” Throughout the 1950s and 60s, rates were increased several times, each over three-year periods.

In 1970, the Postal Reorganization Act transformed the Post Office Department into the United States Postal Service, with a board of governors and Postal Rate Commission in charge of setting new rates. Second-class rates would raise at least once a year throughout the 1970s and 80s. Today, the USPS categorizes its mail into six classes – Priority Mail Express, Priority Mail, First-Class Mail, Periodicals, USPS Marketing Mail, and Package Services and USPS Retail Ground.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

Love all the articles but why is today’s March 3rd article titled March 2nd??!! So have to give it 3 stars for editing.

Thank you. This has been corrected.