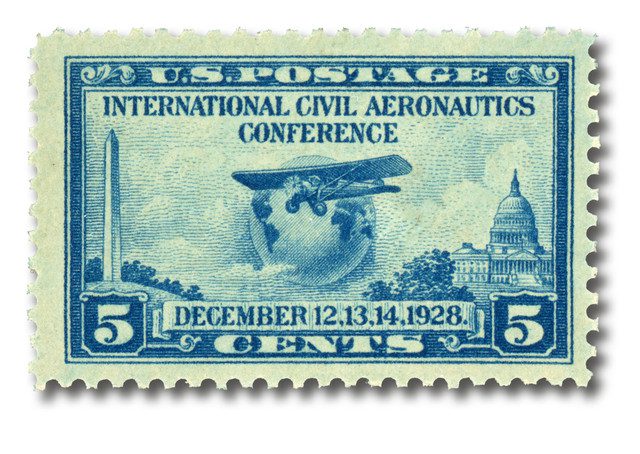

A quarter-century after the Wright brothers first left the ground at Kitty Hawk, the world’s aviation leaders gathered in Washington, DC, to decide just how far—and how fast—human flight could go next. On December 12, 1928, the International Civil Aeronautics Conference opened with a bold mission: to celebrate the past, assess the present, and imagine a future where airplanes would shrink oceans, reshape economies, and bring nations closer together.

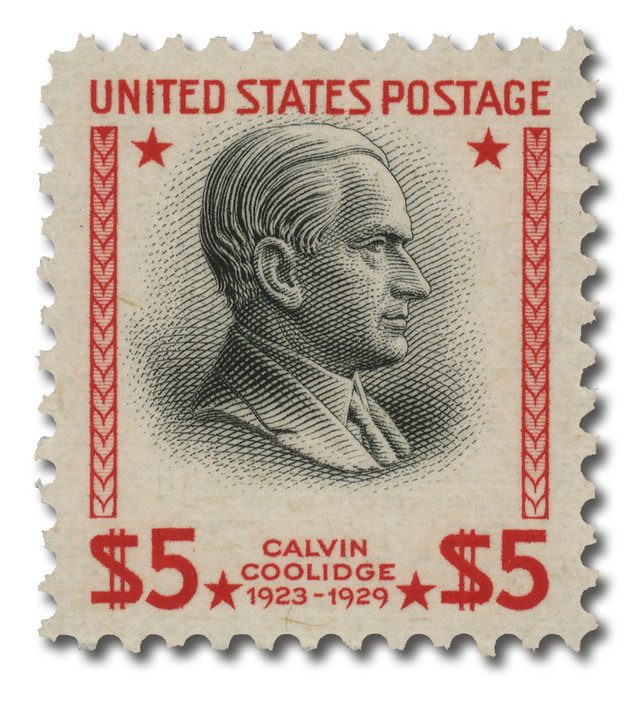

On December 12, 1928, the International Civil Aeronautics Conference officially opened in Washington, DC. The idea for this landmark event came directly from President Calvin Coolidge. A year earlier, in 1927, during a gathering of the Conference of the Aeronautical Industry in the nation’s capital, Coolidge sent a message urging American aviation leaders to think beyond national boundaries. He suggested holding a major international conference the following year to mark the 25th anniversary of the Wright brothers’ first powered flight. But he had a second motive as well: he believed such a conference could strengthen America’s standing as a world leader in aviation, a field that was rapidly transforming modern life.

The aviation industry welcomed Coolidge’s proposal and planning began almost immediately. The dates were set for December 12 to 14, 1928. To build excitement, attendees were invited to an International Aeronautical Exhibition in Chicago the week before the conference. That exhibition offered a remarkable snapshot of American innovation, showcasing nearly every airplane the United States was producing at the time. For foreign visitors, it was an unforgettable introduction to the scale and ambition of America’s aviation industry.

When the conference opened in Washington, Coolidge, serving as honorary chairman, delivered a thoughtful and forward-looking address. He began by reminding the delegates of the moment that had made everything possible: “Twenty-five years ago, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, occurred an event of tremendous significance,” he said. “It was the first extended flight ever made by man in a power-driven heavier-than-air machine.” Coolidge argued that the best way to honor that achievement was to come together to discuss how aviation—still young but growing rapidly—could be expanded for the benefit of humanity.

Coolidge then turned to the future, predicting a world connected by air routes that spanned continents and oceans. “All nations are looking forward to the day of extensive, regular, and reasonably safe intercontinental and interoceanic transportation by airplane and airship,” he noted. He admitted that even imagination might fall short of predicting what aviation could eventually become. But he was certain that expanding air travel would shape civilization itself. While airplanes would bring economic benefits, Coolidge believed their greatest impact would be diplomatic—linking countries more closely through shared interests and easier travel.

The conference drew an impressive international audience. Seventy-seven official and 39 unofficial delegates represented 50 foreign countries. Dozens of American delegates, technical experts, and committee members joined them, bringing the total attendance to 441. Orville Wright attended as the guest of honor, standing as a living connection to the birth of powered flight. Charles Lindbergh, whose 1927 solo transatlantic flight made him the most famous aviator in the world, received a special award in recognition of his achievements and influence.

Throughout the three-day conference, delegates participated in themed sessions that reflected the major challenges and opportunities facing global aviation. The first day examined the development of international air transport and the prospect of regularly scheduled long-distance passenger service. The second day focused on airway infrastructure—navigation aids, weather systems, landing fields, and safety improvements. The third day explored the growing foreign trade in aircraft and aviation equipment, an increasingly important part of the world economy.

The official meetings were only part of the experience. Washington hosted elaborate banquets, receptions, and aerial demonstrations that showcased the latest American aviation technology. After the conference concluded, the delegates traveled by steamship to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. There, at the site of the Wright brothers’ 1903 flight, they participated in ceremonies commemorating the anniversary of humanity’s first successful powered takeoff.

By the time the conference ended, it was widely viewed as a major success. It strengthened international cooperation, encouraged the exchange of ideas, and acknowledged the enormous influence of the Wright brothers’ invention. Even more importantly, it helped set a shared global vision for the future of aviation—a future that would soon transform travel, commerce, and communication around the world.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

We take so much for granted regarding today air transportation but back in the 20’s and 30’s young minds were testing the limits of the human and the air machine. It was trial and error method in which many lives were expended to attain the knowledge we have today. Even the stamp has exceeded many limits but not at the cost of so many lives. No one buys Airmail stamps any more but the mail still moves by air. Collecting stamps helps sustain the history of what it took to get where we are today. Thank you Mystic!

My first commercial flight was on a Super Constellation in 1961. Back then I didn’t appreciate all effort over the years to make commercial aviation possible. Now it is a mature international industry.

During the Vietnam War I flew the Connies 92 times. It was a stable durable airplane.

During the Vietnam War I flew the Connies 92 times. It was a stable durable airplane.

Very enjoyable, to read the daily events that happened. Thank you for posting the stamps and people on that day.