On March 1, 1872, president Ulysses S. Grant signed legislation establishing Yellowstone National Park, the first such park in the world.

Some of the earliest-known inhabitants of the Yellowstone area were the Minnetaree tribe. They named the area’s great river “Mi tsi a da zi,” which means “Rock Yellow River.” They gave the river this name for the rocks that had been turned yellow by the minerals in the water.

The Sheepeaters (of the Shoshone) lived in the area as early as 10,000 years ago. Known as the Sheepeaters because sheep were their primary food source, they were the only year-round residents. In 1805, the Sheepeaters had what was likely their first contact with white men when Sacagawea led the Corps of Discovery into the Yellowstone Mountains. A Shoshone herself, Sacagawea introduced Lewis and Clark to her long lost brother Cameahwait, who showed the expedition the way to the Salmon River.

The following year, expedition member John Colter left the group and is believed to have wandered through areas of the present-day park, making him the first white man to see the Yellowstone area. While wandering in the Tower Falls location, he witnessed inexplicable thermal features. Colter returned home with stories of “fire and brimstone” but most believed his stories were simply delirium. However, fur trappers listened, and began exploring the area almost immediately. They too began to bring back stories of “boiling mud, steaming rivers, and petrified trees,” but their tales were dismissed as myths.

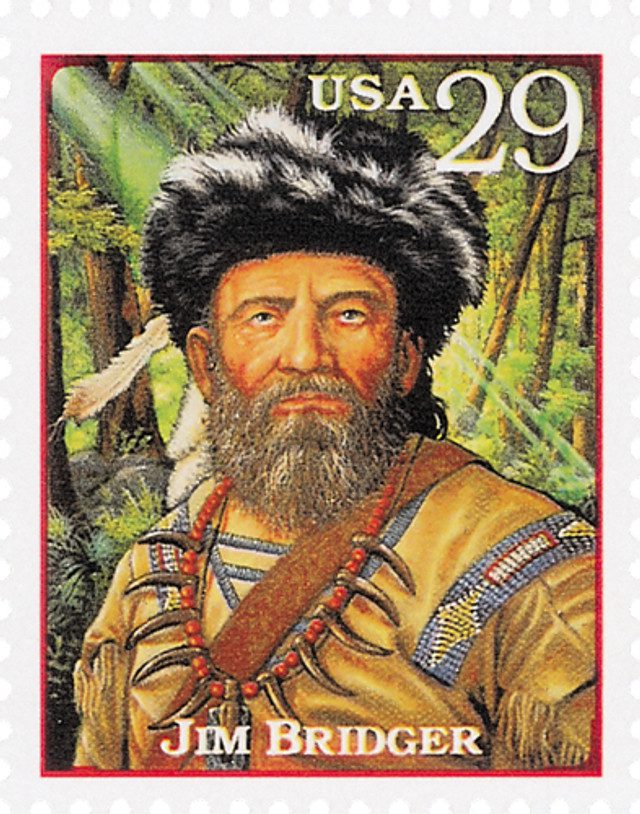

By 1840, the fur trade was declining, but many mountain men remained in the area, including Jim Bridger, who had been there for almost 15 years. As the area’s first geographer, Bridger served as a guide to visitors. Despite his unequaled knowledge of the area, his tales of boiling springs, spouting water, and “a mountain of glass and yellow rock” were ignored.

The first significant exploration of Yellowstone occurred in 1869, led by David E. Folsom, Charles W. Cook, and William Peterson. Their expedition lasted about a month, during which time they measured the heights of the Upper and Lower Yellowstone Falls. Most newspapers doubted their credibility and refused to publish their stories.

The following year, Surveyor General of Montana Henry D. Washburn used information collected from the previous trip to form his own expedition of 19 men. These included Nathaniel P. Langford, Truman Everts, and military escort Gustavus C. Doane. Within two weeks, they came across “boiling sulphur springs” that were too hot to touch, even wearing gloves, and they knew all the rumors were true.

Upon their return, some of the men wrote articles about what they witnessed. Nathaniel Langford was by far the most active in spreading the word about Yellowstone. In addition to publishing “Wonders of the Yellowstone” in Scribner’s Monthly illustrated magazine, Langford set out on a series of lectures promoting the area in 1871.

During one of these lectures, Ferdinand V. Hayden, who had gone on a brief 1859 expedition and was currently head of the U.S. Geological Survey, was inspired to arrange another survey. Hayden successfully lobbied Congress to fund the Hayden Geological Survey, which included geologists, zoologists, botanists, other scientists, photographer William H. Jackson, and artist Thomas Moran. They collected hundreds of specimens, notes, photos, and sketches.

When they returned, Hayden compiled all the information and images into a detailed report he used to convince Congress to reserve the area as a National Park. Hayden believed in “setting aside the area as a pleasure ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people” and warned that there were people that would come and “make merchandise of these beautiful specimens.” Hayden, along with Langford and Montana territory delegate William Clagett, personally visited each member of Congress in what has been called “the most intensive canvass that had ever been accorded a piece of pending legislation.” They delivered each Congressman a bound portfolio with captioned photos.

Hayden’s efforts paid off on March 1, 1872, when president Ulysses S. Grant signed legislation establishing Yellowstone National Park, 18 years before Wyoming would achieve statehood. The park’s first superintendent, Nathaniel P. Langford, received no salary, staff, or funds to maintain the park, so he did little to improve it. However his replacement, Philetus Norris received a salary and minimal funds to maintain the park. Norris increased access to the park, quadrupled the number of roads, and built several facilities.

In 1916, Woodrow Wilson signed legislation forming the National Park Service (NPS). After 30 years of Army administration, the park was placed back into civilian hands (although the Army remained in the park until 1918). The Park’s first NPS Superintendent was Horace M. Albright, who restructured the park to make travel by car easier, as the existing roads had been built for stagecoaches decades earlier. This made Yellowstone more accessible to the “common man.” Albright also oversaw the building of additional campgrounds. His administrative techniques were instilled at other parks around the country, setting the standard for the quality of park service.

Click here for Yellowstone’s official website.

Click here to see what else happened on This Day in History.

PBS has a great documentary on our National Parks. Well worth the time. Thankful that some men had the vision to preserve for all to enjoy.

I have visited Yellowstone many times and learned something new. If you have not been there I do

urged you to go. This is a big volcano some day this area will blow you would not enjoy being any where near Yellowstone that day. I hope I do not live to that day.