On May 14, 1935, US and Cuban pilots flew the first international airmail sky train.

A sky train (also called an air train) consists of a motor airplane pulling two glider planes in tow that don’t have motors. The phrase is a reference to the railroads, in which a locomotive would haul two wagons.

The idea for the flight was developed on March 28, 1935, when a group of glider enthusiasts visited the Cuban secretary of communications, Dr. Pelayo Cuervo Navarro. They were promoting a potential international airmail flight between Miami and Havana. The goal of the flight was to show that regular sky train service could be made between the US and Cuba. The flight was also intended to honor the first airplane flight between the US and Cuba in 1913, made by Agustín Parla. Navarro approved the idea and placed Parla in charge of organizing it. Cuba contributed 3,000 pesos to project and by May, they were ready for the flight.

On May 14, 1935, the sky train departed Miami at about 1 p.m. They flew about 90 miles over the sea (240 miles total). People crowded the streets of Havana to witness the sky train, some standing on the roofs of buildings to get a closer look as it flew over. At about 3:10, La Cabaña fired two cannon shots to announce that the sky train was in sight. As the sky train then flew overhead, the crowd of more than 50,000 fell silent as they watched.

The main plane, piloted by Elwood Klein and Agustín Parla then released the two gliders and flew west toward the Columbia airport. The gliders did some aerial tricks before landing. At 3:25, Jack O’Meara landed his G-448 in front of the capitol. Three minutes later, Richard DuPont landed his G-11180.

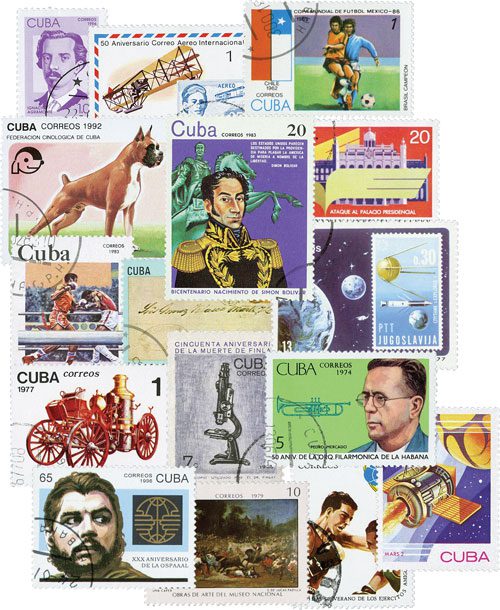

The planes had carried 148 letters. Most of these letters had been mailed the night before to the local post office in Miami bearing the current 2¢ National Parks stamps. Once in Havana, special Cuba stamps produced for the event were affixed and an official cachet was added. However, it was decided at some point between then and the return flight on May 19 that the covers wouldn’t be sent back. The Cuban cachets were then invalidated with the word “Nulo” written over them in red ink and the Havana postal authorities removed the special stamps.

About 35,000 of those special stamps were issued in Cuba to be placed on mail for the return flight. Of those, 10,000 were unperforated and 25,000 were perforated. The entire stock of stamps sold out in an hour. The pilots then received $3,000 from the sale of these stamps. In all, they would carry 48 pounds of mail back to the US. The flight left Havana on May 19 at 9:05 a.m. They stopped at Key West for customs and landed in Miami at 3 p.m.

Speaking about the flight, O’Meara said, “The flight had two main objectives: to prove the practicability of this type of flying, particularly over a large body of water, and to prove the feasibility of flying the mail under these conditions. We did not try to make a speed record of any sort. We averaged about 68 miles an hour. It was strictly an experimental flight. Faster speed will come later when gliders are so designed that they can be towed by faster planes.” He went on to say that they were “royally entertained by Cuban government officials.”

Click here for more Cuba stamps.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

So was it ever done again, or was this a one-time event?

Jack was my Great Uncle. This was the first and only mail flight like this. Most of the 148 letters were confiscated. Fortunately Jack tucked a few pieces in his jacket and I have them now (signed by all 3 pilots). Jack is acknowledged as the founding father of gliding (Elmira, NY) and died in an experimental glider way too young. He was something. There should be a movie made about the early gliders.

Thanks Michael for “the rest of the story”.

Great article. Learned something new. Keep up good work