On May 20, 1927, Charles Lindbergh began his famous flight across the Atlantic aboard the Spirit of St. Louis.

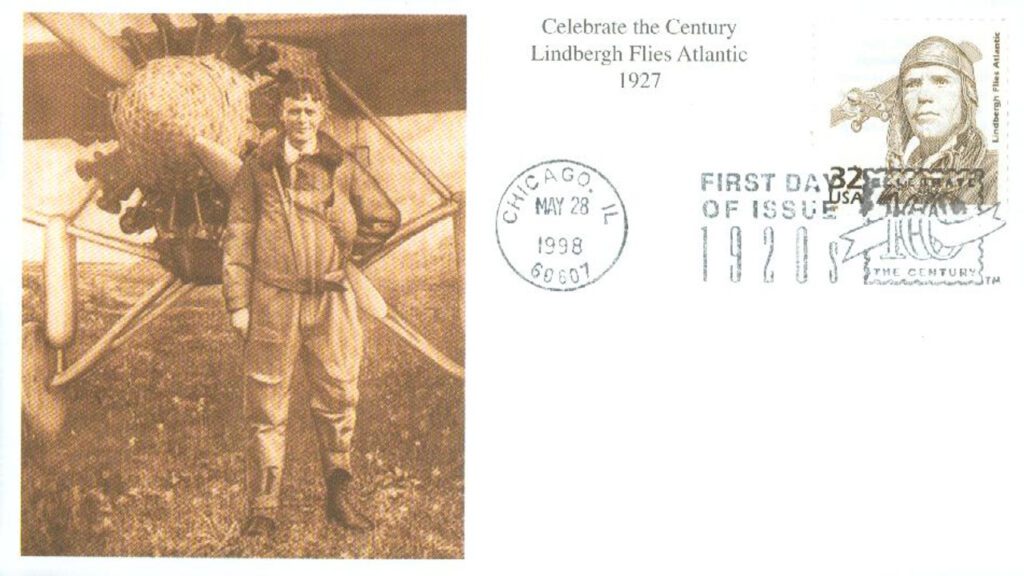

Born in 1902, Charles Augustus Lindbergh was taught to be completely self-reliant. It was this mindset, along with the spirit of an explorer, that led to the flight that would make him an aviation pioneer.

“Lucky Lindy” began his career at the age of 20, when he left the University of Wisconsin to enroll in flight school. Soon he was a barnstormer, offering plane rides for $5 a person and performing as a stunt pilot at fairs. He also trained with the Army Air Service and went on to fly airmail between St. Louis and Chicago.

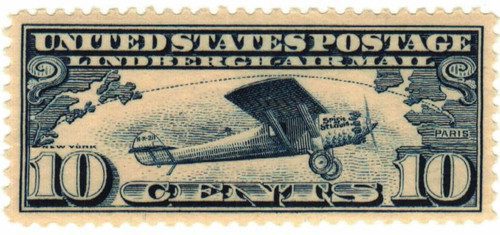

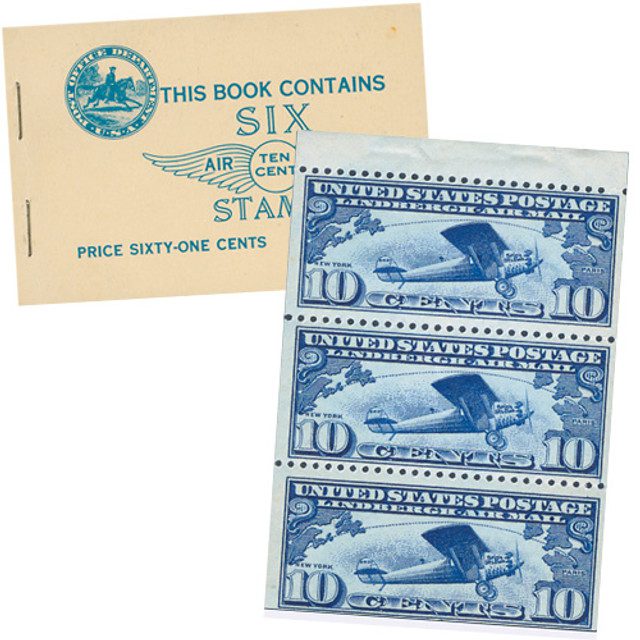

Lindbergh was an airmail pilot for the United States Postal Service (USPS). He was very familiar with the risks of flying. Between the years 1919 and 1926, 19 USPS pilots had died in accidents. In fact, Lindbergh himself had crashed on his St. Louis to Chicago route. It didn’t dampen his enthusiasm for flying, though. He dreamed of trans-Atlantic flights – carrying mail and passengers – becoming an everyday occurrence.

Since 1919, a New York City hotel owner, Raymond Orteig, had offered a $25,000 reward to the first pilot to fly non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean. Several pilots attempted to earn this prize, but all failed – some were injured or even killed. In 1927, this unclaimed prize came to Lindbergh’s attention. He believed the trip was possible with the right plane.

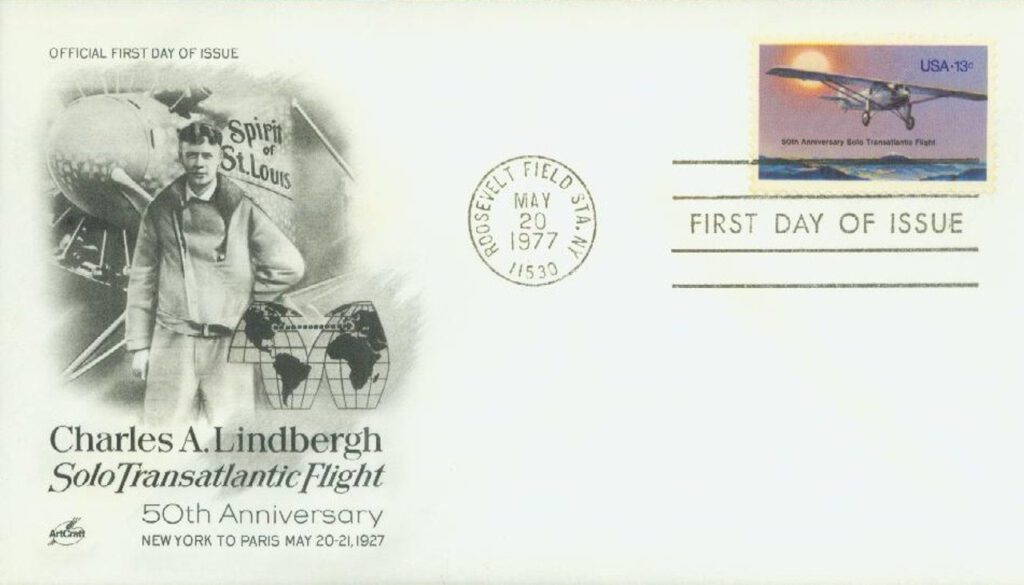

Lindbergh convinced a group of St. Louis businessmen to give him the financial support he needed to build a special airplane of his own design. He named the plane the Spirit of St. Louis.

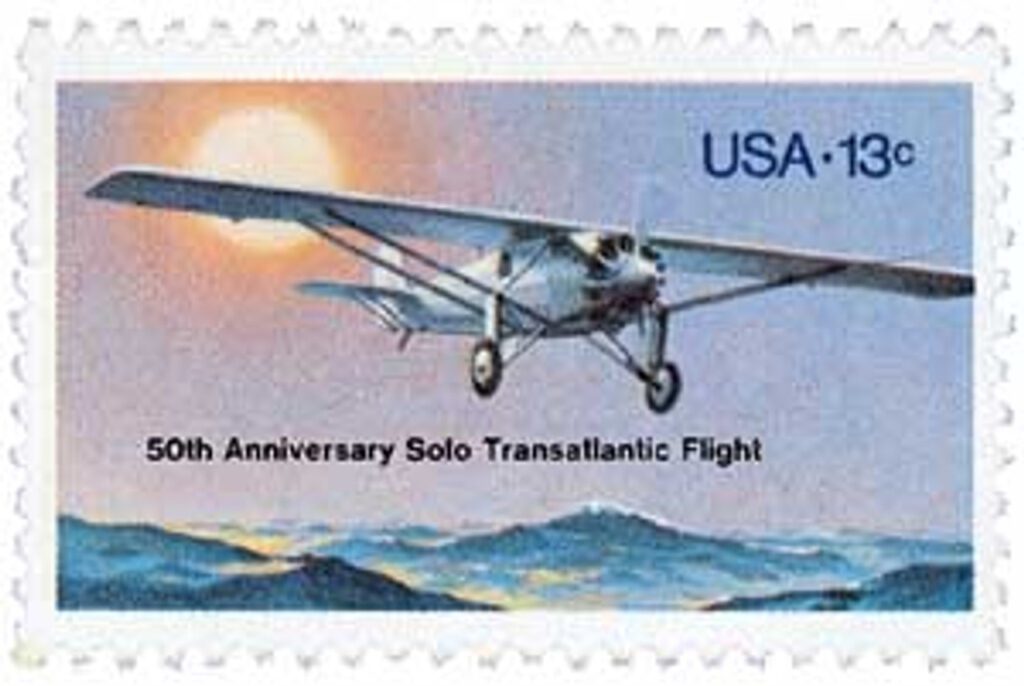

On May 20, 1927, at 7:52 a.m., Lindbergh took off in the Spirit of St. Louis from Roosevelt Field, located near New York City. Lindbergh’s plane was so heavy with fuel it barely cleared the telephone lines to begin the daring flight. When fully loaded with fuel for the flight, the 27-foot Ryan M-2 aircraft weighed slightly more than the average US automobile. Lindbergh insisted that the plane be purposely constructed to be uncomfortable to help keep him awake during the long journey.

Lindbergh’s only tools were a compass, an airspeed indicator, and his own navigational skills. His greatest challenge on that long, lonely flight was to stay awake, as he began to feel tired just four hours in. The storms he encountered took him off course and became navigational challenges. While over the Atlantic Ocean, he saw two fishing boats, circled down, and tried to ask them to point to land. Unsuccessful, he continued on and soon spotted the coast of Ireland. He knew at that point that his flight was a success, and he flew on to Paris in higher spirits.

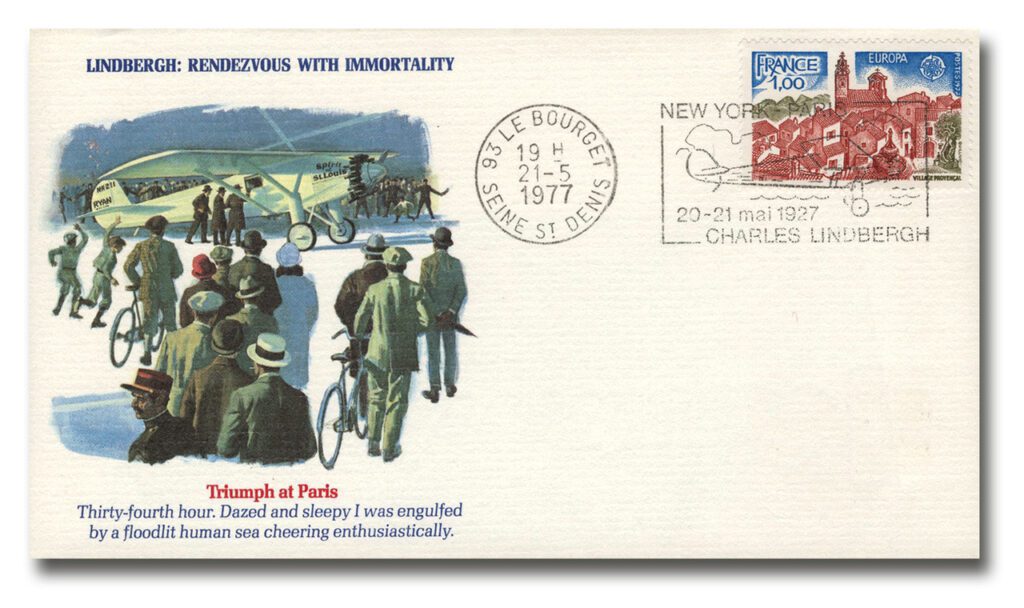

Cruising at an average airspeed over 100 miles an hour, Lindbergh crossed Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Ireland, England, and the English Channel. Thirty-three-and-a-half hours and 3,600 miles later, he landed near Paris at Bourget Field where a wildly excited crowd of well over 100,000 rushed onto the runway to meet him. The next day, another crowd formed outside the American Embassy where he was staying, cheering and waving hats and handkerchiefs. Lindbergh received the Legion of Honor Medal from the president of France, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor by US President Coolidge.

Lindbergh’s historic flight made him an instant celebrity. A US Navy cruiser transported Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis home. Following a hero’s welcome, the pilot and plane began a lengthy goodwill tour across the US and Latin America. On the final leg of the tour, Lindbergh flew the Spirit of St. Louis to Washington, DC, and presented the plane to the Smithsonian Institution.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

keep up the excellent articles and work. It inspires me to take out my albums and continue with my stamp collecting. THANKS

I am now almost 92, and I was a pilot during WWII in the Pacific, and learned to fly at 18, and didn’t learn to drive a car until I was 32. When I was a child I had a toy that was a replica of the Spirit of St. Louis.

Thank you for your service, sir. Thank you also for sharing a little of your experiences of those remarkable times.

We should never forget our history and learn from our past.

It’s impossible to understand how popular Lindbergh (don’t forget the H- a favorite peeve of his)

was at this time. It’s like Beyonce and U-2 in one- global facination!. He had political problems because he was warning America about how advanced Germany was before the war- people thought he was a sympathizer- aside from some personal complexities. His feat was unbelievable to most people.[ some french flyers may have crossed the other way before him but crashed in Maine-with little evidence left. If it had been Boston- we may have never heard of Charles.] Rosevelt wouldn’t let him fly during the war, but, showed a p-39 group how to feather their engines and shoot down Yamamoto in New Guinea. He worked with Howard Hughs to develop the machine gun belt :as in “the whole nine yards”.

Eisenhower eventually made him a general. His grave is in Kipahulu on Maui. His stone reads: “May his wings all ways fly in the wild blue yonder”

He was the greatest.!!

He did warn against getting involved in Europe BEFORE Dec 11, 1941. He was against Roosevelt’s violation

of the neutrality act. Was the first to warn that Churchill wanted us in the European theater so bad to save

his precious British Empire.

One more stamp (James Stewart’s Birthday) https://www.linns.com/news/us-stamps-postal-history/2016/may/born-may-20-james-stewart.html

3184m is not lithographed or multicolored, but rather single color engraved.

Man, … Charles Lindberg was indeed a brave American to set out to do what he successfully did! If his airplane had had a mechanical problem while he was over the ocean, or he crashed because he fell asleep for a few minutes, or the long air flight hours or the weather conditions prevented his successful trip, he would have HELPLESSLY lost his life … which would have been a TERRIBLE tragedy !! How could he have survived … it took him 33 hours after HE WAS AWAKE TO TRY TO MAKE THE TRIP !! I AM SURPRISED BY HIS GREAT COURAGE AND DESIRE TO DO WHA6T HE DID. Like I said at the beginning, he was a GREAT AMERICAN !!

If he flew at 100mph for 33 plus hours, he would have covered over 3300 hundred miles not 1000.