On September 17, 1862, Union and Confederate troops assembled at Antietam Creek for a 12-hour battle. By sunset, one in five men had become a casualty of the bloodiest one-day battle ever fought on American soil.

The early months of 1862 began well for the Union in the Eastern Theater. George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac was within a few miles of Richmond by June. However, Robert E. Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia on June 1. The Union’s advantage disappeared as Lee fought McClellan aggressively in the Seven Days Battles, forcing McClellan and his army to retreat down the Virginia Peninsula.

Lee then began his Northern Virginia Campaign, outmaneuvering and defeating Major General John Pope and the Army of Virginia, including the Second Battle of Bull Run during the last two days of August. Four days later, Lee launched his Maryland Campaign – a bold move to strike a blow on Union soil.

The Civil War’s major battles had been fought on Confederate ground until the Maryland Campaign. Lee’s offensive had several objectives. Moving his troops north meant leaving war-torn Virginia for the undamaged farmland of Maryland and Pennsylvania, where they could resupply. In addition to cutting off the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad line that supplied Washington, DC, Lee also hoped to incite an uprising in the border state of Maryland.

Lee understood that military victories were one of several ways to win the war. Simply making the Northerners and their government unwilling to wage war was another. An invasion could damage Northern morale just before the Congressional elections of 1862, which in turn would tip public opinion in favor of Democratic candidates and force Lincoln to negotiate an end to the war.

Crossing the Potomac River into western Maryland, Lee divided his army by sending Stonewall Jackson with a force to capture Harpers Ferry. The site where John Brown staged his famous raid in 1859, Harpers Ferry was a gateway to the Shenandoah Valley and a vital link in the Confederate supply line now guarded by 12,000 Union troops.

With a remaining force 38,000 strong, Lee took up a defensive position at Antietam Creek near Sharpsburg. McClellan pursued with troops that outnumbered Lee’s by 2-to-1. The Union troops arrived overnight, in plain view of the Confederates. A Pennsylvania soldier recalled, “…all realized that there was ugly business and plenty of it just ahead.”

As the sun rose on September 17, Union troops began their assault on the Confederates positioned in cornfields to the north of the town. Lee had gathered his forces on high ground west of Antietam Creek with General James Longstreet commanding troops at the center and right. Stonewall Jackson’s men were located on the left. To their rear was the Potomac River, with only one suitable crossing if retreat became necessary.

McClellan’s plan was to “attack the enemy’s left,” and when “matters looked favorably,” to attack the right, and if either of those was successful, he would order his men to advance on their center. For seven hours following daybreak, Union forces staged three major attacks on the Confederate left, moving north to south. General Joseph Hooker led the first, followed by General Joseph Mansfield’s soldiers, and then General Edwin Sumners. McClellan’s plan broke down as Lee moved his men to withstand each Union advance.

One-and-a-half miles south, Union General Ambrose Burnside attacked the Confederate right and attempted to capture a bridge. A small enemy force stationed on higher ground was able to keep Burnside’s men pinned down for three hours. Taking the bridge at 1 p.m., Burnside then took two hours to reorganize his troops only to be turned back by Confederate General A.P. Hill’s reinforcements who arrived from Harpers Ferry.

Unable to inflict substantial damage on either flank of the Confederate force, McClellan didn’t advance on the center and a number of his troops never saw battle. Those who did fought stubbornly until sunset. Over 22,717 men lay dead or wounded when night fell. After each side buried their dead the next day, Lee’s army withdrew across the Potomac to Virginia, ending his invasion of Maryland.

Although the battle was inconclusive, Northerners were relieved by the outcome. Encouraged by the sense of victory, President Lincoln seized the opportunity to deliver the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring all slaves held in rebellious states to be free. After months of fighting and thousands of losses, it was the first major action by the federal government to end slavery in the United States.

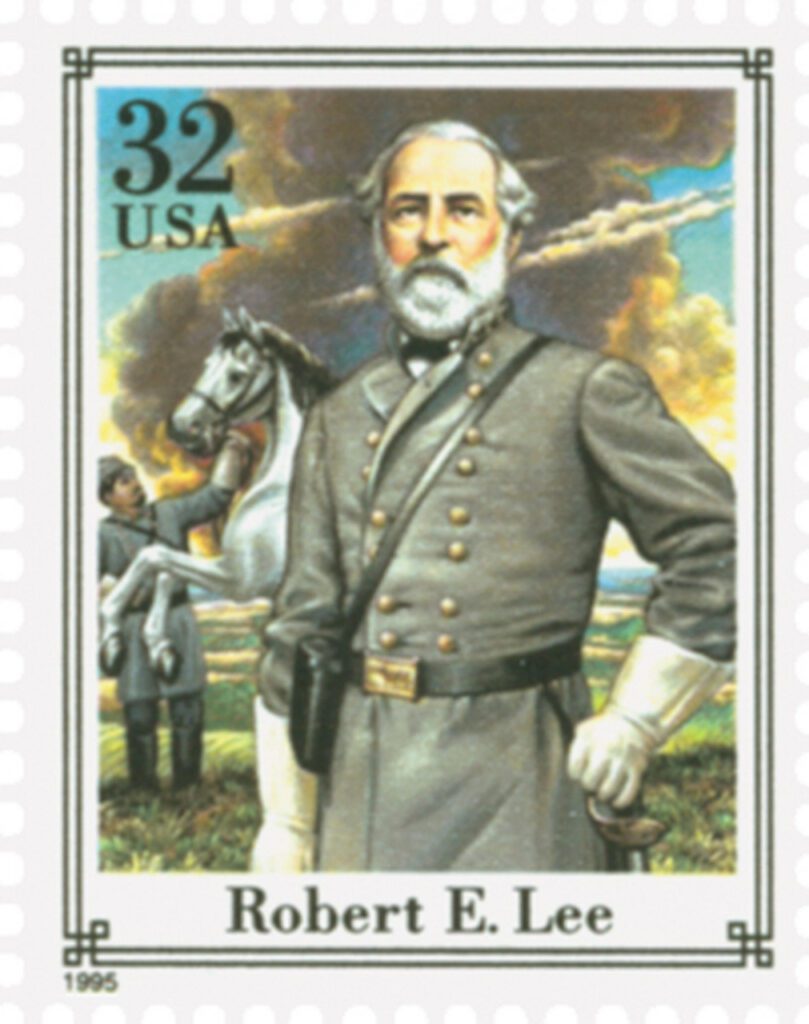

Click here to see a larger version of the painting show on US #4665.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

My uncle who was a pilot during the Korean War, had a relative; great uncle or cousin that died in Gettysburg.

McClellan was slow to get his army in position to attack Lee, he was slow and un-coordinated to attack on on September 17, and slow to follow up on Lee’s retreat. As Lincoln commented, “McClellan has the slows.”

As with any event of any kind, especially battle, it is very, very easy to sit back and critique every aspect afterwards. However, in real time, and especially in the heat of battle, there is considerable confusion and many other factors, to contend with. Most particularally during the times of the civil war. Just try to imagine being there back then involved in such a time of this or any other civil war battle you want to name. Arm chair warriors and Monday morning quarterbacks indeed !

I don’t agree with most of what Thomas said here, but I have to go with the professional historians who have studied the Battle of Antietam and McClellan’s military career in general. They are very critical of McClellan’s actions before, during, and after Antietam. Re. McClellan’s career, their assessment is that he was very able in training and logistics and that his men were very supportive of his leadership. However, as a battlefield commander, he was hesitant and overly cautious. He constantly complained that he was outnumbered, even when he had the superior force. He had the army, but he was reluctant to use it.

Mistake. I meant to say that I don’t ‘disagree’ with most of what Thomas said.