Abigail Adams, America’s second first lady, lived a life shaped by intelligence, resilience, and an unwavering sense of purpose. Born Abigail Smith on November 22, 1744 (November 11 in the Old Style calendar) in Weymouth, Massachusetts, she grew up during a time when girls were rarely encouraged to pursue learning. Yet Abigail’s curiosity, sharp mind, and determination made her one of the most influential women of the Revolutionary era. Her letters, ideas, and leadership helped shape the emerging nation, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire Americans today.

Much to Abigail’s regret, she never received a formal education. Even so, she grew up in a home where books were treasured. Surrounded by the libraries of her father and grandfather, she absorbed works of philosophy, theology, Shakespeare, the classics, ancient history, government, and law. She taught herself to read and write with confidence and developed the ability to analyze current events through a historical lens. Abigail believed that studying the past was essential—not only for understanding the world around her, but for preparing her to act wisely in times of difficulty. This love of learning stayed with her throughout her life.

In 1759, Abigail met a young, ambitious lawyer named John Adams. At first, some family members believed Abigail was too quiet for the outspoken John, but the two found common ground in their shared love of reading and discussion. Within three years, their friendship had grown into affection, and they began writing a series of warm and often playful letters. John affectionately called Abigail “Miss Adorable,” while she referred to him as her “Dearest Friend.” They married on October 25, 1764, in a ceremony performed by her father. After the wedding, they settled into a modest cottage next to John’s childhood home and began building both a family and a partnership that would last a lifetime.

Their marriage soon became intertwined with the birth of a nation. In 1774, John traveled to Philadelphia as a Massachusetts delegate to the Continental Congress. Abigail remained at home with their children, but distance did not weaken their bond. Instead, it sparked a remarkable series of letters that documented the early years of the Revolution. Abigail described the hardships of wartime, including shortages, inflation, and the responsibilities of raising five children and managing the family farm alone. She also offered her husband political advice, observations from local newspapers, and reports on how ordinary citizens responded to unfolding events. These letters remain one of the most valuable first-hand accounts of life during the Revolutionary era.

In 1784, after years of separation, Abigail joined John in Paris, bringing their son John Quincy and daughter Nabby with her. Life in Europe gave Abigail a new cultural education. She observed French manners, court customs, and political attitudes—knowledge that later proved helpful during her years as first lady. The following year, when John became America’s first minister to Great Britain, Abigail carried herself with dignity and tact even in the face of lingering hostility from the British court. By 1788, the family returned to their home in Braintree (now Quincy), Massachusetts, where Abigail took pride in expanding and improving their beloved “Old House.”

Her public role grew again in 1789, when John Adams was elected vice president under George Washington. As the nation’s first Second Lady, Abigail formed a close relationship with Martha Washington and often assisted in social duties, drawing on her experience abroad. When John became president in 1797, Abigail’s influence only increased. She oversaw formal entertaining and became the first hostess of the unfinished White House. Her active involvement in politics earned her the nickname “Mrs. President,” a sign of both respect and criticism in a young nation still debating women’s roles.

Two issues defined Abigail’s political beliefs: women’s rights and the fight against slavery. As early as the 1770s, she argued that women should not be bound by laws they had no voice in shaping. She believed strongly in women’s education and legal equality. Abigail was also firmly anti-slavery, calling it both a moral evil and a threat to democracy.

In 1801, after John lost the presidency to Thomas Jefferson, the couple retired to their Braintree home. Though political disagreements had strained their friendship with Jefferson, Abigail renewed contact after the death of his daughter, helping rebuild a bond that would last through their later years. She proudly followed her son John Quincy Adams’s rising political career, though she did not live to see him become president. Abigail Adams died of typhoid fever on October 28, 1818. Her final words to her husband captured a lifetime of devotion: “Do not grieve, my friend, my dearest friend. I am ready to go. And John, it will not be long.”

Her legacy of intelligence, courage, and moral conviction continues to resonate, reminding Americans of the power of an educated mind and a steadfast spirit.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

A few slight corrections: Adams was named as America’s first “Minister” to Britain (like an ambassador), not as “Prime Minister.” In the election of 1800 which was decided by the electoral college in 1801, Adams did lose to Thomas Jefferson, but they hadn’t been friends for several years because of deep political differences while Jefferson was Vice President during Adams’ Presidency.

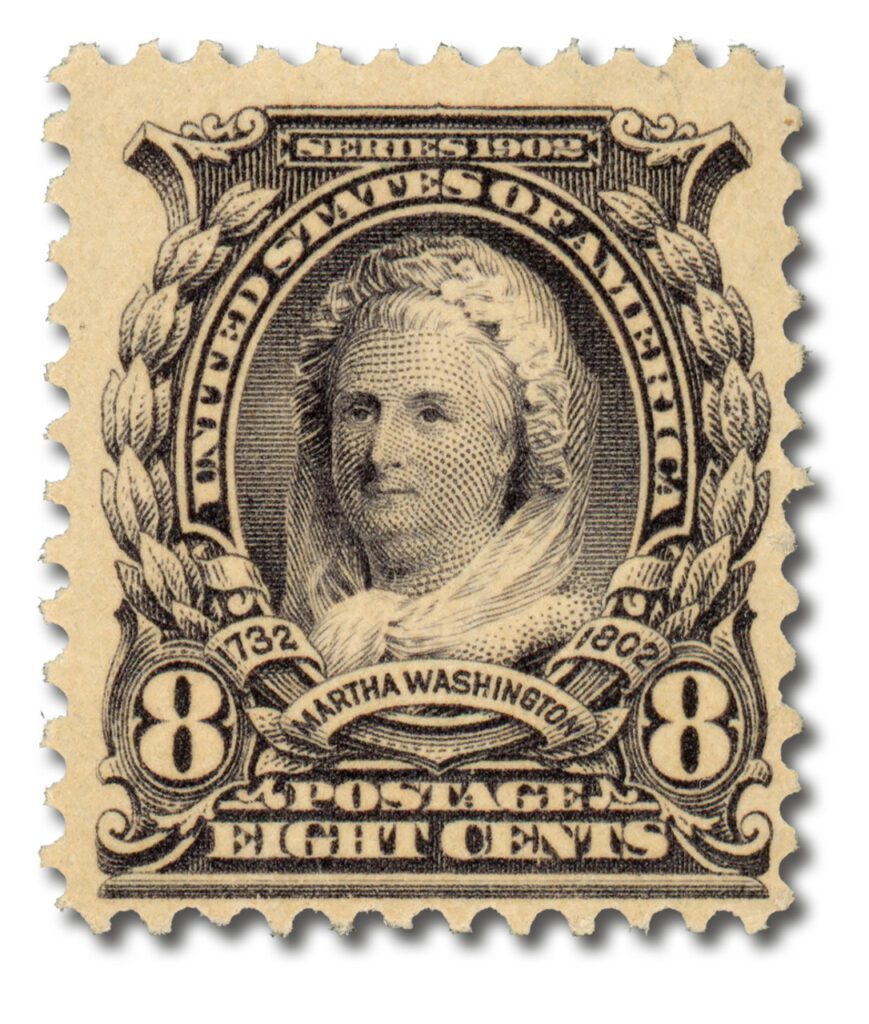

The greatest of all “first ladies” of the United States, who fully deserves to be on one of the new Money bills in the near future. The US post office has produced throughout its existence many stamps rightly honoring George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Why did John Adams and his first lady not receive the same honor, outside the known Presidential series of stamps, as their contributions as founding persons have been equally great.

I’m certainly in agreement. Abigail Adams was a remarkable lady, and their correspondence worthy of reading.

This kind and dedicated woman is hard to find this days. She should be read by all First Lady of the nation and learned from it.

Abigail Adams and Eleanor Roosevelt are the best First Ladies we’ve ever had.

Nice read about a former first lady. Eleanor Roosevelt features on a commemorative stamp of India using the Gandhian spinning wheel. ?

John Quincy was already in France with his father when Abigail joined him in 1784. Nabby and Charles came with her though.

One of the great love stories in our country’s history. Although dis-liked by many during his time, no one influenced revolutionary ideas more than John and Abigail Adam’s. Not mentioned in the article are the loss of a child, the disease and tragedy the Adam’s endured during their lifetime together. To read their letters is to understand what undying love truly means and how moral character played into our country’s beginnings. I agree with the above comments about Adam’s and Roosevelt, but I also believe you can add Jackie and do not deny Michelle Obama’s influence around the world. These ladies had “balls” as powerful women, and should be included in any discussion with Harriett Tubman, Susan B. Anthony, Rosa Parks and many other great women. Power to the Women!