Founding Father John Jay was born on December 12, 1745, in New York City, Province of New York.

Jay’s family moved to Rye, New York three months after he was born and he spent much of his childhood there. Jay’s mother taught him at home until he was eight, at which point he went to study with Anglican priest Pierre Stoupe for three years. Jay returned to studying with his mother before entering King’s College (later Columbia University) at age 14.

After graduating from college, Jay worked as a law clerk before being admitted to the New York bar. He opened his own law office and became a member of the New York Committee of Correspondence in 1774. That same year he was made a delegate to the First Continental Congress. Initially, Jay hoped to settle the British tax violations peacefully and helped write the Olive Branch Petition. After the British burned Norfolk, Virginia, however, he supported the calls for independence.

After the First Continental Congress, Jay wrote the Constitution of New York. He also served on a committee that monitored Loyalist activities. In 1777, he was made the chief justice of the New York Supreme Court of Judicature. He was also elected president of the Continental Congress in December 1778. He held that post until September 1779, when he was made minister to Spain. He was tasked with securing aid and support. While Spain initially didn’t recognize American independence or Jay’s role as minister, they eventually gave him a loan for $170,000.

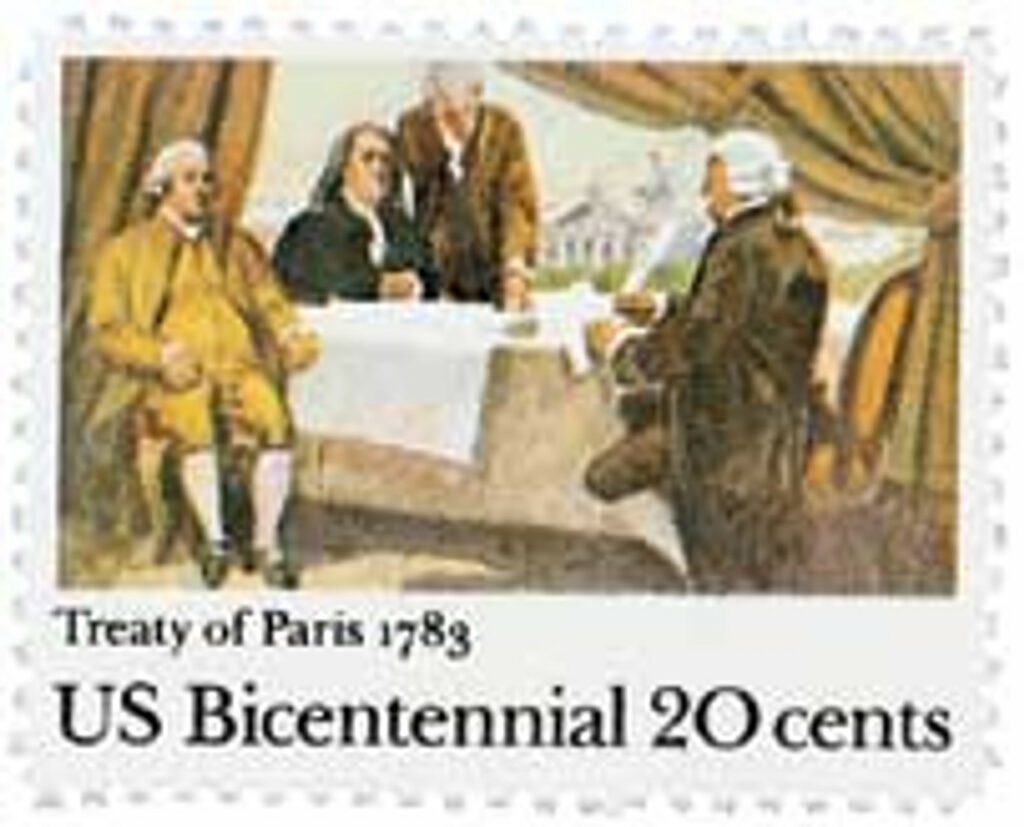

After the war, Jay helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris. He then served as secretary of Foreign Affairs. In 1788, he helped write The Federalist Papers with Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, which promoted the ratification of the US Constitution.

After the Constitution was ratified, President Washington needed to make several political appointments. In September 1789, he offered Jay the position of secretary of State. Though a new title, it would’ve been the same duties he was already performing as secretary of Foreign Affairs. Jay turned down the offer, but Washington had another in mind – chief justice of the Supreme Court. According to Washington, the position “must be regarded as the keystone of our political fabric.” After Jay accepted, Washington officially nominated him on September 24, and the Senate unanimously confirmed him two days later. Jay swore his oath of office on October 19.

For the first three years, most of the Supreme Court’s time was spent establishing rules and procedures, admitting attorneys to the bar, and overseeing circuit court cases in the federal judicial districts. In his spare time, Jay aided President Washington and spread his ideas while touring the circuit courts.

In 1790, Jay established the court’s independence after Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton asked the court to support legislation over state debts. Jay said that the court could only rule on the constitutionality of cases being tried and wouldn’t take a position for or against the legislation. In the six years Jay was chief justice, the Supreme Court only heard four cases. These cases involved state statute requirements and pensions for war veterans. They also included whether the states were subject to the rulings of the court and if the court had the power to decide the law.

A decade after the Revolutionary War ended, tensions between the US and Britain rose again. British troops refused to give up forts and British warships hassled American vessels. President Washington sent Jay to England to work out a treaty. Passed in 1795, the Jay Treaty settled some of these issues and remained in effect for 10 years. (Though a replacement treaty was unsuccessful and the War of 1812 followed.)

Jay retired from the Supreme Court in 1795, the same year he was elected governor of New York. President John Adams re-nominated him for the Supreme Court, but he refused due to poor health. Jay retired from politics in 1801, spending his final years on his farm in Westchester, New York. He died on May 17, 1829.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Click here to see what else happened on This Day in History.

I read these American history articles EVERY day. Seven days a week. I look forward to them every morning. I really do appreciate them so much. Thank you all for your efforts and well written research. I hope they continue. Great job.

Please keep them going.