William Jennings Bryan was born on March 19, 1860, in Salem, Illinois. Known as “The Great Commoner,” Jennings ran for president three times, but is remembered for his impassioned speeches on a variety of topics, including anti-trust, anti-imperialism, prohibition, populism, and trust-busting.

The fourth of nine children, Bryan was home schooled by his mother until he was 10 years old. He enjoyed public speaking, giving his first speech when he was just four. Bryan attended Illinois College, where he participated in many debates and speaking contests. He graduated at the top of his class in 1881 and went on to earn a Bachelor of Laws from Chicago’s Union Law College (present-day Northwestern University School of Law).

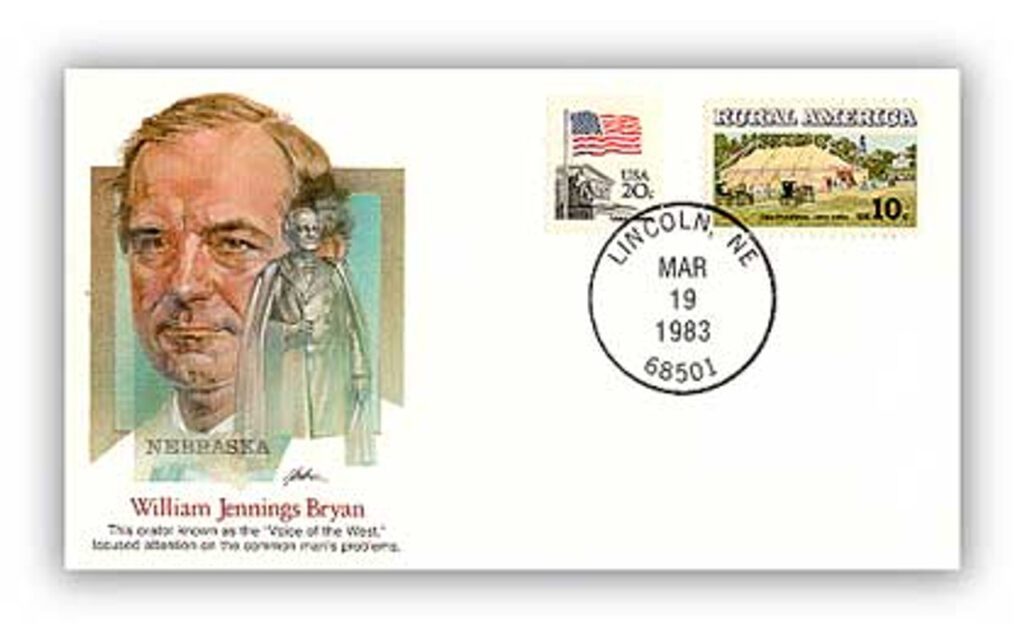

In 1887, Bryan established a law practice in Lincoln, Nebraska and began participating in politics. Delivering stirring campaign speeches for others, he was encouraged to run for Congress in 1890. He won that seat with promises to reduce tariffs and the power of trusts and adjust the value of silver coinage compared to gold. Bryan was appointed to the House Ways and Means Committee and won reelection in 1892. Though he was unable to save the Sherman Silver Purchase Act following the Panic of 1893, Bryan got an amendment passed that created the first peacetime federal income tax.

In 1894, Bryan failed to win election to the Senate. He then spent his time touring the country giving speeches to gain support for his causes, including free silver, and raising his national profile before the next election. At the 1896 Democratic National Convention, Bryan delivered his stirring “Cross of Gold” speech in support of free silver over the gold standard. By the fifth ballot, he earned the party’s presidential nomination. Just 36 years old, he was the youngest person to receive a presidential nomination by a major party, a distinction he still holds today.

Banking on Bryan’s speaking abilities, he went on a national tour, giving 600 speeches before about five million people in 27 states. Though he earned solid support from farmers and silver miners, he ultimately lost the election to William McKinley. Bryan remained popular in his party, and after the Spanish-American War broke out, the Nebraska governor tasked him with forming his own regiment. Bryan recruited 2,000 men, but the war ended before they could be sent to Cuba.

In 1900, Bryan unanimously won the Democratic presidential nomination. Anti-imperialism was his primary focus, though he also pushed for free silver and opposing trusts. Bryan campaigned extensively, delivering about 63,000 words a day, between giving four speeches as well as smaller talks. He ultimately lost that election and spent the next few years lecturing. In 1901, he began publishing his own newspaper, The Commoner. Within five years, he had 145,000 subscribers, and it was one of the most popular papers of the time. Bryan then spent three years in Europe and Asia, delivering speeches and recording his thoughts on “The Old World and Its Ways.”

When he returned to the US, Bryan regained support within his party and was selected as the Democratic presidential nominee on the first ballot. However, he lost the 1908 election to William Howard Taft. Bryan is the only major party nominee since the Civil War to lose three US presidential elections, and his combined total of 493 electoral votes is more than any other candidate who was never elected president.

Bryan opted not to run for president in 1912 and instead used his influence in the party to push for Woodrow Wilson’s election. After Wilson was elected, he made Bryan his secretary of State. In that role, Bryan supported the reduction of tariff rates, a progressive income tax, anti-trust legislation, and the creation of the Federal Reserve System. He also worked with 30 countries in a series of bilateral treaties and oversaw US involvement in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico. Bryan resigned his post in 1915 following disagreements with the Wilson administration’s response to World War I. After the US entered the war, Bryan offered his services to Wilson, agreeing to show his support through speeches and articles.

In his later years, Bryan spoke out in support of the eight-hour work day, minimum wage, the right of unions to strike, and women’s suffrage, though most of his efforts focused on prohibition and opposition to teaching evolution. Despite being a top contender for the 1920 nomination, Bryan declined to enter the election. He was a driving force behind the Florida real estate boom of the 1920s and served on the Board of Trustees at American University. Bryan represented the World Christian Fundamentals Association during the 1925 Scopes Trial, but died five days after the trial ended on July 26, 1925. Though historians debate his legacy, many recognize he played a major role in shaping public policies for more than 40 years.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

Wonderful politician, but I’m glad he was on the losing side of the 1925 Scopes trial.

Wonderful politician, but I’m glad Bryan was on the losing side of the Scopes trial.

He was actually on the winning side in that trial as the defendant was found guilty of teaching evolution in violation of Tennessee law.

Yes, he was on the winning side of the battle, but the losing side would win the war. Like many others of this time period, especially President Wilson, what they did right could not undo what they did wrong. That’s why history has not been kind to them.

He was certainly on the losing side in the Prohibition debate, as “the eighteenth article of amendment is hereby repealed.”

The “Cross of Gold” was his 3 hr speech that shot him into history and almost the White House. My History teacher in High School, recited the last paragraph and at the end he, like Bryn, held out his arms as if hanging on a Cross. We were shocked by his actions, not only did he recite from memory but the action silenced us. Thank you for giving us a history about not only the stamps but the person or action that brought the stamps to life.