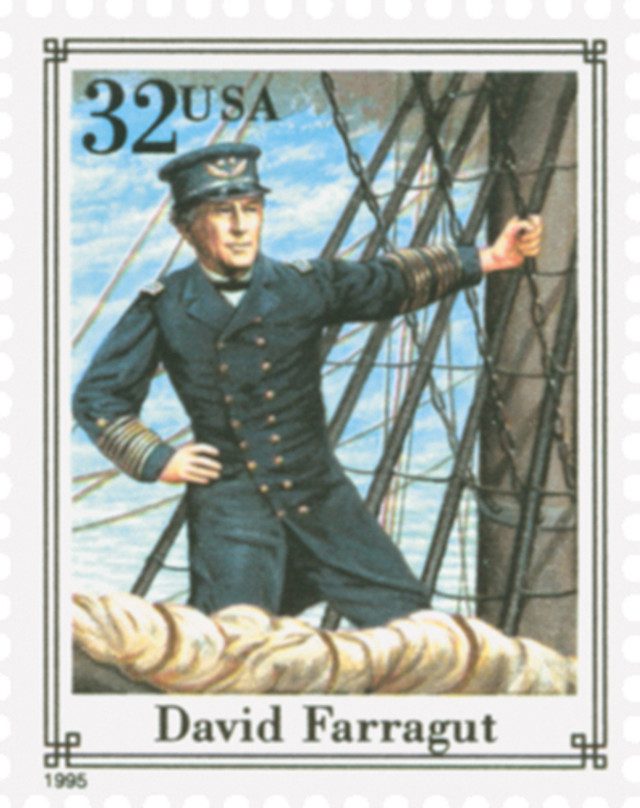

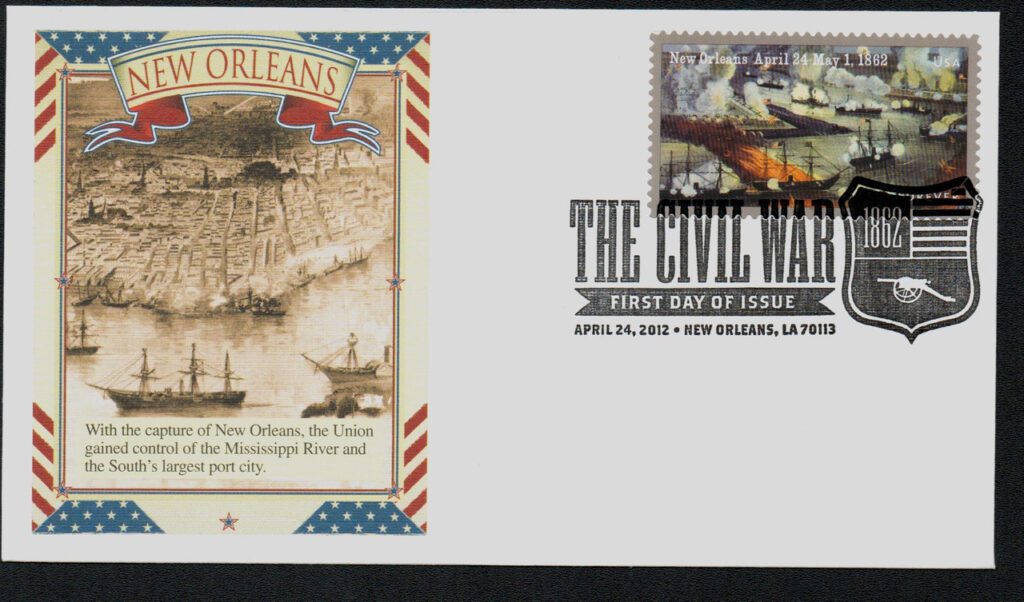

On April 29, 1862, Union Admiral David Farragut captured New Orleans from Confederate forces. Capturing one of the Confederacy’s largest cities, known as the “Jewel of the South,” this was a major victory and turning point in the Civil War.

At the start of the Civil War, Winfield Scott, the Union’s commander, devised a plan to divide the Confederacy and cut off trade by taking control of the Mississippi River. The capture of New Orleans – a thriving center of trade in the mid-1800s – was a step toward accomplishing both goals.

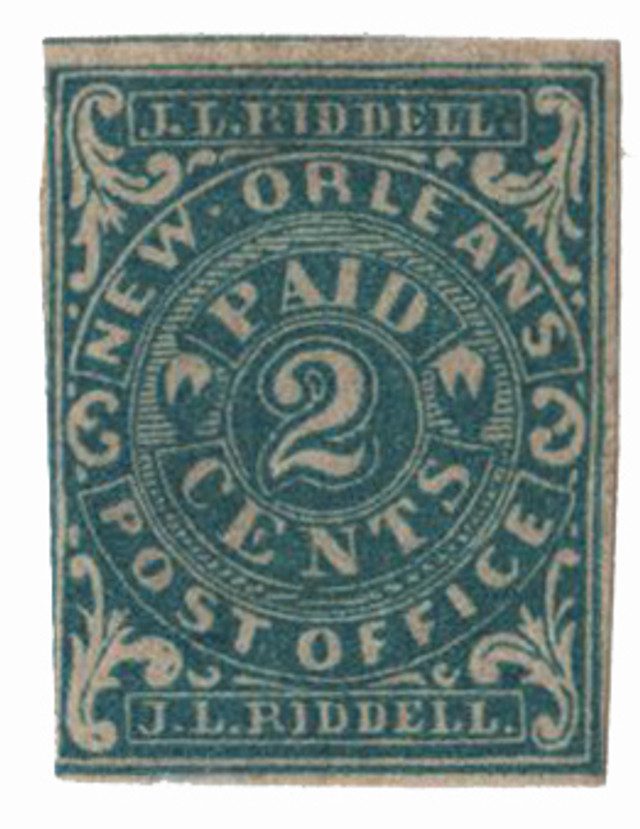

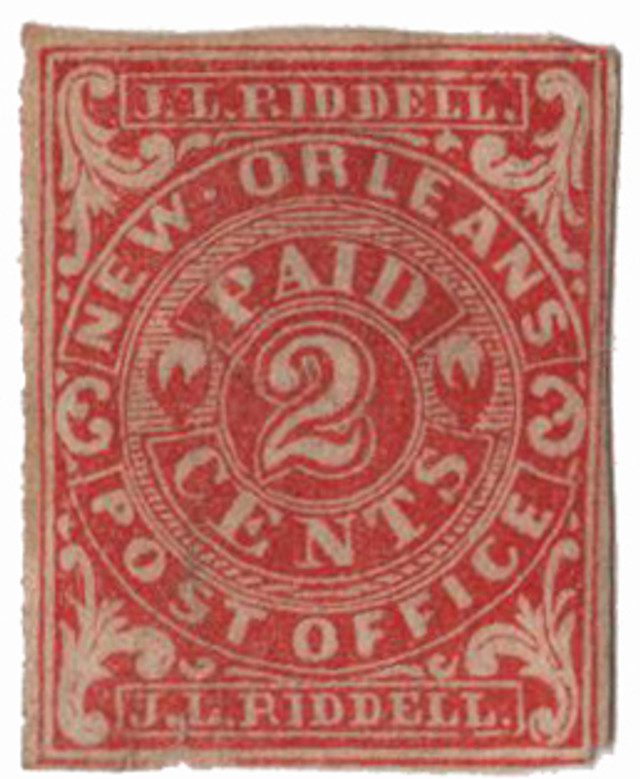

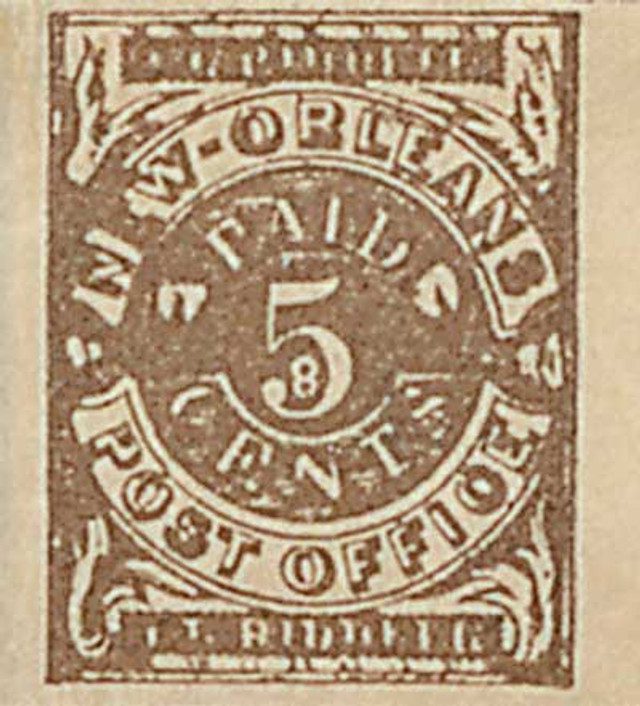

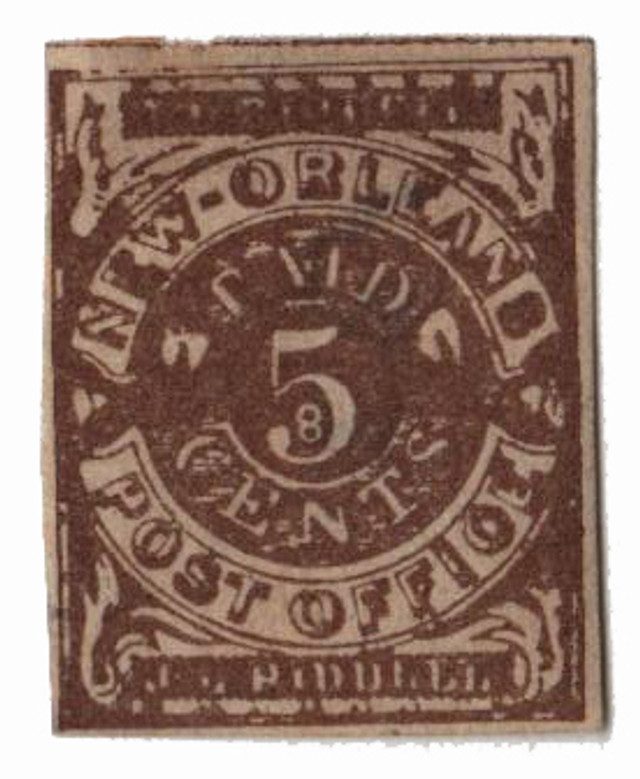

These Confederate Postmasters’ Provisional stamps were created for use in New Orleans between June 1, 1861, when the use of US stamps stopped in the Confederacy, and October 16, 1861, when the first Confederate government stamps were issued. They remained in use into early 1862.

New Orleans’ location at the mouth of the Mississippi made it the major shipping port for the river. Friendly trade relations with the North were vital to the continuing prosperity of New Orleans during the Civil War, so the majority of residents preferred to stay neutral. However, Louisiana’s governor pushed for secession and ordered the state’s militia to seize the forts and arsenals within its borders.

In January 1862, Admiral David Farragut was given command of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron and tasked with putting New Orleans under Union control. However, Forts Jackson and St. Philip guarded the city from the south. If the Union wanted to capture the city and strike a blow to the Southern economy, he had to first disable these forts.

After months of assembling a fleet, including mortar schooners commanded by Farragut’s foster brother, David Porter, the Union ships traveled upriver toward the forts. On April 18, Porter’s ships began the bombardment, firing over 1,400 shots on the first day. Fort Jackson was closer, so it suffered more damage, but neither structure was severely harmed.

Beginning at 2:00 a.m. on April 24, two columns of ships passed the forts in three divisions. One line fired on Fort Jackson on the west bank, while the other concentrated on Fort St. Philip to the east. After getting past the forts, the lead boats were confronted by the small Confederate fleet. The Southern Navy lost twelve vessels and the Union only one.

With no other obstacles in his way, Farragut commanded his ships to sail for New Orleans. Confederate Major General Mansfield Lovell, commander of the limited Confederate forces in the region, knew the city was destined for capture. He evacuated his 3,000 poorly equipped men by rail to Camp Moore, 78 miles north. His message to the Confederate War Department read, “The enemy has passed the forts. It is too late to send any guns here; they had better go to Vicksburg.”

The weary soldiers at Fort Jackson were without shelter, food, or drinking water. Fort commander General Duncan initially refused to surrender, but the men mutinied and he had to give up the fort. Fort St. Philip soon followed suit. On April 29, Farragut sent a small force of men to raise the stars and stripes over New Orleans, a sign to all that it was now in Union hands.

On May 1, 1862, Union Major General Benjamin Butler arrived in New Orleans with a force of 5,000 men. As the commander of Fortress Monroe, he was the first to offer refuge to fugitive slaves, who he called “contraband of war.” Butler was chosen to lead the takeover of the South’s most populous city because of his political talent, rather than military successes.

Residents vastly outnumbered Butler’s troops. He sought out Union supporters, who were rewarded with jobs assisting the Federal troops and cleaning the city. The general won favor with the residents when he expanded the sewer system, which diminished the annual yellow fever epidemic. He also distributed food captured from the Confederates to the poor of New Orleans. Author Chester G. Hearn credits Butler with saving the city’s residents from starvation and disease. The city’s free Black men were organized into infantry regiments, keeping pro-Confederacy factions under control. Since the Union blockade, New Orleans had lost its prime source of income because of lack of trade. Butler used his connections with New England merchants to restart the shipping of cotton.

The good Butler did for the struggling city of New Orleans was tempered by unwise decisions and corruption, though. While governing, he acquired two nicknames, “Beast Butler” and “Spoons.” The second developed from his habit of stealing silverware from the Southern houses he stayed in. The other name resulted from his ordering the execution of a man for tearing down the US flag from the New Orleans mint. Butler caused international conflict when he imprisoned French Champagne magnate Charles Heidsieck for spying. It was these types of actions that led to his removal as commander of the Department of the Gulf on December 17, 1862.

Farragut’s fleet continued up the Mississippi and captured Baton Rouge and Natchez in May. Vicksburg was defended by Confederate fortifications on high bluffs and would not be overtaken for another year. The Union Navy controlled all but 200 miles of the 2,320-mile river.

The seizure of New Orleans may have convinced European powers, such as Great Britain and France, not to recognize the Confederacy as a nation. With Butler’s programs, the Southern government lost the support of the city’s residents as well.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

Tomorrow we’ll look back on an important event in the life of George Washington… be sure to come back and find out more.

Again, some lesser-known details from history. Always interested in the Civil War. Thanks Mystic.

I often wonder where and how does Mystic have such a vast collection of such unusual stamps such as the “Confederate Postmasters’ Provisional stamps” shown at the beginning if this article? They certainly add to the enjoyment of collecting stamps if only for the history but a little pricy for my budget.

These are wonderful history lessons….compliments to the folks that do the background and put these together…great stuff!