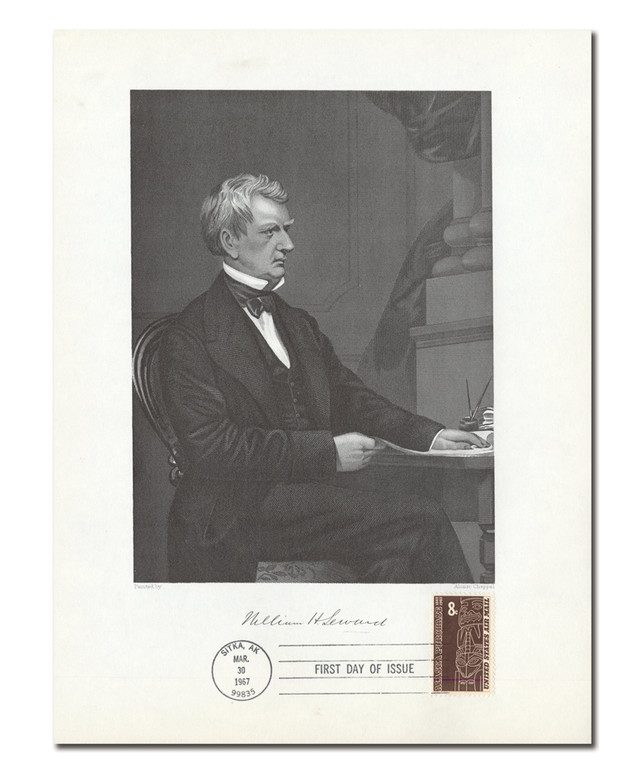

William Henry Seward was born on May 16, 1801 in Florida, New York. Seward was a bright child that enjoyed school (it was reported that instead of running away from school to go home, he’d run away from home to go to school). He went on to attend Union College, taking time off to teach in Georgia before returning and graduating with high honors in 1820.

Seward then studied law, passed the bar, and moved to Auburn, New York, where he met newspaper publisher and political boss Thurlow Weed, who would remain a close ally for many years. It was during his time in Auburn that Seward became increasingly interested in politics. With Weed’s support, Seward was elected to the New York State Senate in 1830 with the Anti-Masonic Party. In the coming years, he emerged as a leader of the Whig Party, but lost both his senate seat and a run for the governorship in 1834. With his political prospects gone, Seward followed his family’s wishes and returned to practicing law. He also worked for the Holland Land Company, a group of Dutch investors that bought large tracts of land in western New York. Seward’s break from politics was brief. In 1838, Weed convinced him to run for governor of New York again, and this time he won. Seward served two terms as governor and focused much of his attention on prison reform and improving education. Seward left the governorship in 1842 in considerable debt and had to return to practicing law once again.

During his break from politics, Seward took on a pair of controversial cases, defending felons accused of murder. Though the cases created an uproar in the local community, they made him famous throughout the North. He earned further praise for launching an appeal in support of an anti-slavery advocate who was sued by a slave owner for assisting escapees on the Underground Railroad.

Seward again returned to politics in 1849 when he was elected to the US Senate. During his tenure, he became a leading critic of the Compromise of 1850, which supported the slave trade in the South. Seward emerged as one of the nation’s leading antislavery activists, stating that slavery was immoral and that there was “a higher law than the Constitution.”

Winning re-election in 1855, Seward continued to speak out against slavery. He also ran for president in 1860, but lost at the Republican National Convention to Abraham Lincoln. Seward was initially unsure of Lincoln’s political abilities, but campaigned for him and soon found they worked well together. Seward became one of Lincoln’s most trusted advisors and was appointed secretary of State. Though he had once declared that civil war was an “irrepressible conflict,” Seward spent his first few months in office trying to avoid the war. Once it began, Seward made it his mission to arrest Confederate sympathizers in the North. He was also extremely concerned with preventing European countries from offering aid to the Confederacy. In late 1861, he helped ease tensions following the Trent Affair, in which the US Navy had seized Confederate envoys aboard a British ship. On April 14, 1865, just after the war ended, Seward was among the targets of John Wilkes Booth and his conspirators to overthrow the government and mount an insurgency. Though he was stabbed several times, Seward survived the attack.

After recuperating from his attack and a previous carriage accident, Seward continued to serve as secretary of State under Andrew Johnson. Seward worked to reintegrate the South during Reconstruction, though some criticized him for being too lenient. Seward was also interested in expanding America’s territories. Though he failed in the Pacific and Caribbean, he had success much farther north. In 1867, he offered to purchase Alaska from the Russians for $7,200,000, or less than 2-cents an acre. At first, few people considered this a profitable acquisition and called it “Seward’s Folly” and “Seward’s Icebox.” But as furs, copper, and gold began to pour forth out of the “frozen wasteland” (petroleum had not yet entered the picture), Seward began to look less foolish.

Following the inauguration of President Ulysses S. Grant, Seward left office and spent his final years traveling the world. He died on October 10, 1872.

FREE printable This Day in History album pages |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

At first, few people considered this a profitable acquisition and called it “Seward’s Folly” and “Seward’s Icebox.” I think this should read “unprofitable”

Thank you for the information