On November 28, 1922, skywriting was first used for advertising in American skies. It quickly grew in popularity, with advertisers finding a new way to deliver messages to a wider audience.

US stunt and later airmail pilot Art Smith was reportedly a skywriting pioneer. He was said to have attached flares to his aircraft when he did his stunts and ended each one by writing “Good night” in the sky.

Britain’s Royal Air Force is often credited with developing skywriting during World War I. Pilots discovered that if they ran paraffin oil through the exhaust of their planes, it would create white smoke that would remain in the air.

They used this smoke as a means to communicate with ground forces when other methods of communication were unavailable. They also used it to create smoke screens to conceal the movements of troops and ships. After the war was over, RAF Captain Cyril Turner believed that skywriting could also be used for advertising. In 1922 he forged a deal with a London newspaper on Derby Day to write out “Daily Mail” in the sky.

Later that year, Turner took his idea to the US. On November 28, 1922, he flew over New York City and wrote “Hello USA.” The following day he returned to the sky to tell people where they could find him at “Vanderbilt 7200.” The hotel received 47,000 calls in two-and-a-half hours based on his aerial advertisement.

Eventually Turner became the head pilot of the Skywriting Corporation of America, the nation’s first and most successful commercial skywriting company. Over the years they worked with companies such as Ford, Chrysler, Lucky Strike, and Sunoco, spelling out advertisements in the sky such as “Drive Ford” and “Lucky Strike Means Fine Tobacco.”

Soft-drink company Pepsi was so excited by the idea, they bought their own plane specifically for skywriting. In 1932, it made its first flight. Over the course of a day, the plane spelled out “Drink Pepsi Cola” over the streets of New York City eight times. Pepsi eventually expanded to 14 planes that traveled the country and world, writing more than 2,200 slogans in the sky in a single year.

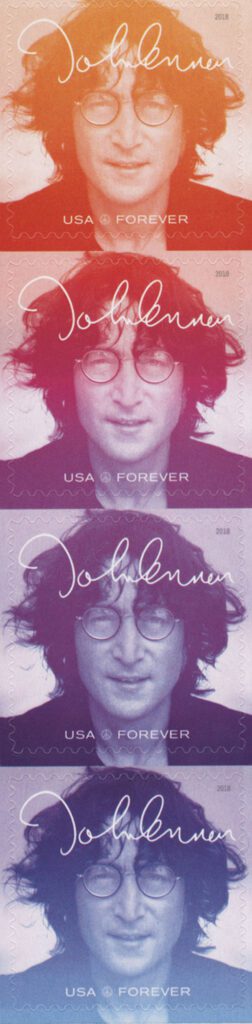

Skywriting faded in popularity with the increase of television advertising, though it would still be popular at air shows and for other purposes. One of the longest messages came in 1969 over Toronto, “War is over if you want it – Happy Xmas from John and Yoko.”

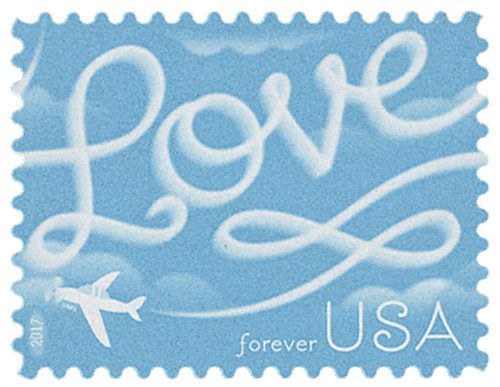

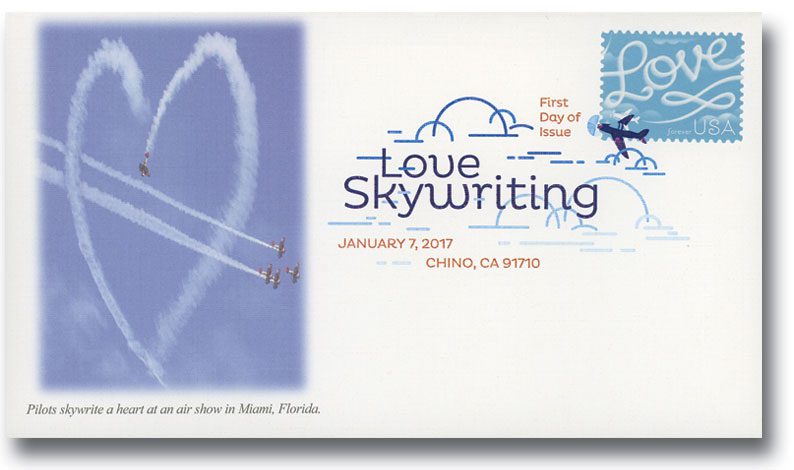

There are two types of skywriting: traditional and skytyping. Both forms feed paraffin oil through the plane’s exhaust to create a trail of white smoke. In traditional skywriting, a switch in the plane’s cockpit controls the release of oil. For skytyping, a computer controls when the smoke is released. In both, the letters can be about a mile high and a mile wide.

Traditional skywriting requires a specially trained pilot. They create a detailed flight plan with the letters written in reverse. Each maneuver is precisely timed so the message is legible on the ground. Skytyping is faster and easier, but less elegant. Five planes fly in parallel lines, releasing puffs of smoke to form the message. Unlike traditional skywriting, skytyping consists of broken dots instead of solid lines.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

Very interesting explanation. Thanks Mystic

I remember seeing “Drink Pepsi Cola” in the sky when I was a youngster, probably around 1953/54, over the small town of LaFollette, Tennessee. It was a sight for a country boy to behold at that time and place.