On May 4, 1942, the World War II Battle of the Coral Sea began. It was the first fight between aircraft carriers; in fact, the ships weren’t even in sight of each other.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was the start of a plan to remove the U.S. and its allies from the South Pacific. In the following months, Imperial Japan attempted to control the Philippines and the Solomon Islands.

The Philippines were dotted with U.S. military bases, and the Japanese Air Force began bombing them within days of the Pearl Harbor attack. The destruction of planes and buildings, combined with the devastation of America’s fleet harbored in Hawaii, left the troops without the supplies and firepower necessary to combat the experienced Japanese forces. General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), ordered his forces to retreat to the Bataan Peninsula and defend it until relief arrived from America.

After months of bravely defending the region, U.S. and Philippine forces ran low on food, medicine, and ammunition. The Allies surrendered to the Japanese on April 9, 1942. More than 60,000 Filipino and 15,000 American prisoners of war were forced to walk for six days and nights to a prison camp. This became known as the Bataan Death March because thousands of men died along the way. Though the Allies were defeated at Bataan, the four-month battle slowed the Japanese advance in the South Pacific.

In order to further strengthen this position in the South Pacific, the Japanese planned to invade Port Moresby, New Guinea, and Tulagi in the Solomon Islands. The territory, which was controlled by Australia according to a League of Nations mandate, sat about 500 miles north of the “Land Down Under.” Japan hoped the strike would eliminate Australia and New Zealand from the war. The U.S. decoded their messages and sent ships to the area to thwart the invasion.

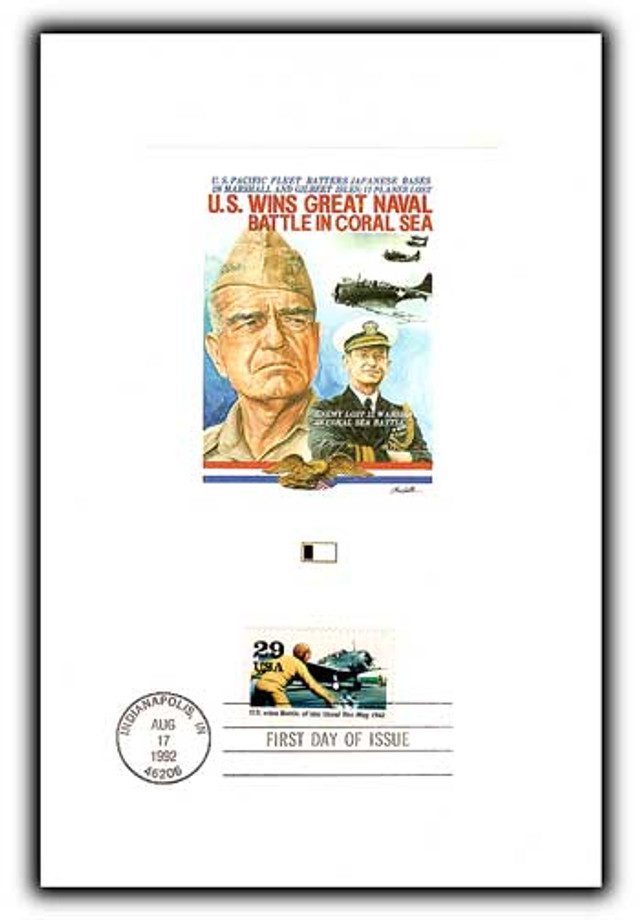

The Japanese forces arrived at Tulagi on May 3 and quickly occupied the island; the small Australian force that had been there evacuated shortly before. The next day, American Admiral Frank Fletcher ordered 60 aircraft to launch three consecutive strikes on the Japanese forces off Tulagi. They managed to catch the Japanese by surprise, sinking on destroyer and three minesweepers, as well as damaging four ships and four seaplanes. In spite of the damage, the Japanese continued building a seaplane base at Tulagi and were able to launch reconnaissance missions within two days.

Radio intelligence soon revealed that the Japanese were planning to land at Port Moresby on May 10. In response, Admiral Fletcher planned to surprise them again, by launching a battle at sea on May 7. Over the next few days, American and Japanese forces sent out repeated reconnaissance missions and engaged in minor skirmishes.

On May 7, Task Force 44 (which, at the time, was temporarily redesignated as Task Group 17.3) led by Royal Rear-Admiral Crace attempted to intercept the Japanese invasion force, but were spotted by enemy reconnaissance aircraft. The Japanese then launched an air attack, sinking the USS Neosho and Sims. Meanwhile, American forces found the Japanese Covering Group that was escorting the invasion force and launched their own aerial attack, sinking the Japanese carrier Shoho. That night, the Japanese decided to call off the invasion of Port Moresby.

The next morning, on May 8, the Japanese launched 27 aircraft under cover of darkness in search of the Allied Task Force. They failed to find them and only six aircraft returned. Then, shortly after dawn, American and Japanese carrier groups finally spotted each other. Around 9:15, each force sent their warplanes out to attack. Within two hours, the Americans landed several devastating shots on the Shokaku, damaging it severely. Japanese aircraft had crippled the USS Lexington, as well. While repairs were underway, a spark set off a series of explosions through the Lexington. Though the ship suffered several uncontrollable fires and had to be scuttled, nearly all of the sailors were rescued. The forces withdrew for the day and the battle ended in a draw, though the Allies claimed some victories.

The Japanese advance in the Pacific had been halted for the first time and their continual string of victories was ended. It was the first carrier-versus-carrier battle in history. And in Australia, generations to come would refer to the day’s events as the “battle that saved Australia.”

The Japanese didn’t invade Port Moresby because of the loss of planes, which they used to cover the infantry. This was the first time the Japanese were turned away from their objective and played a part in the eventual defeat of Imperial Japan.

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

Great story about our history.

Very thorough and interesting. Thanks!

As a boy in dinner camp in the fifties, one of our camp counselors mentioned that her brother had survived the sinking of the Lexington at Coral Sea. He also survived the sinking of his next ship, the Cartier Princeton in 1944. It wasn’t until years later that I realized what momentous times he endured.

The U.S. and allied effort to stop the Japanese was a victory in that Japan was

stopped. This led to the Japanese Naval leaders desiring to get rid of

the American carriers once and for all and they planned to attack Midway Island

to draw the remaining three serviceable Carriers (Yorktown, Enterprise and Hornet)

into a trap sert by Adm. Nagumo and his four fleet carrier strike force. The U.S.

intercepted and decoded the attack messages and the rest was history. The Japanese

lost four fleet carries, numerous aircraft and most of all the core of their experienced

senior pilots. The U.S. did lose the Yorktown, but with the industrial capacity of the

U.S. they replaced the Yorktown many times over. The Japanese, on the other hand,

did not have the capacity to replace four frontline fleet carriers.

Great story, two of my brothers were involved in the Coral sea battle.

My father was at the Battle of the Coral Sea on the Lexington. He didn’t really like to talk about it much, but he did mention being picked up by an Australian ship after the Lexington sunk and they had to abandon it. My father has since passed away, but I know he would probably have been proud knowing, that what so many sacrificed for, has not been forgotten.

I think mention should be made that Gen. MacArthur was sent to Australia from Bataan. He was one of the main planners that carried the war back to Japan and defeat.