On February 19, 1945, the Battle of Iwo Jima began. It was one of the bloodiest of the whole war, with over 44,000 combined casualties.

By early 1945, the war in Europe was nearing its end as the Allies closed in on Hitler’s regime. The war in the Pacific was also steaming along, as the Allies island-hopped their way closer to Japan. They then turned their sights to Iwo Jima (Japanese for “Sulphur Island), a small 10-square-mile island 750 miles south of Japan. The Allies needed to capture the island to aid their attack on the Japanese mainland, and the Japanese commanders knew that.

Anxious to bring an end to the war, American military commanders were resolved to take the island and establish an airbase there. This would put an end to the Japanese raids, attacks, and early warnings. It would also provide a place for fighter escorts to join the B-29s attacking the Japanese mainland as well as an emergency landing field for bombers that were damaged on their way back from Japan.

The American force consisted of the V Amphibious Corps, composed of three Marine Divisions commanded by Major General Harry Schmidt. The 80,000-man assault force was unprecedented. Seventh Air Force bombers began bombing the island in December 1944, long before the Marines reached Iwo Jima. The plan for D-Day was that the Marines would land on the southeastern coast, take the lower airfield, west coast, and Suribachi, before moving north.

The Americans departed the Marianas on February 13, 1945. Initially, the Marines requested 10 days of naval bombardment on the island. However, the Navy said they did not have enough time or ammunition, and they ultimately settled on a four-day bombardment. Poor weather in the days leading up the amphibious landing decreased the effectiveness of this bombardment. Two days before the landing, a group of 100 Navy and Marine underwater demolition frogmen approached the shore. The Japanese believed this was the main landing and began firing on the men and landing craft. Naval ships then returned fire, as the Japanese had revealed some of their positions.

The battle began at 6:45 am on February 19 when Admiral Richmond Turner announced, “Land the landing force!” The troop ships then steamed toward the island as the naval bombardment and air force bombings continued. At 9 in the morning, the first troops and landing craft stormed the shore. However, their advance slowed dramatically as they encountered the soft black sand. Men were slowed to a crawl while vehicles overturned and were left immobile. One report stated, “Resistance moderate, terrain awful.”

After just a few minutes, there were 6,000 Marines ashore, but they were backed up on the beach because of the slow progress through the sand. While the bombardments had silenced the enemy guns initially, the Japanese slowly increased their fire on the beach. Then at about 10:00 am, General Kuribayashi instructed his large weapons to unleash their full fury. Marines on the beach were caught by surprise and had nowhere to run to take cover, they could only burrow into the sand. Despite this devastating fire, some of the Marines managed to move toward their objectives. By 10:30, the 28th Marines reached the western shore, severing Iwo Jima, though this would be their furthest advance of the day.

With the dismal landings and move inland behind them, the Marines then looked toward Mount Suribachi, their next major objective. They launched their first wave of attacks the next day. However, their artillery was not strong enough to break through the Japanese concrete pillboxes that filled the mountainside. The fight for Suribachi would be slow and hard-fought. On that first day, the Marines overran 40 Japanese strong points and gained 200 yards, but lost as many men. At the same time, Marines elsewhere on the island went for their objective – the first airfield. They spent the day under heavy enemy fire crossing the airfield, but managed to capture part of it that day and the rest the following day.

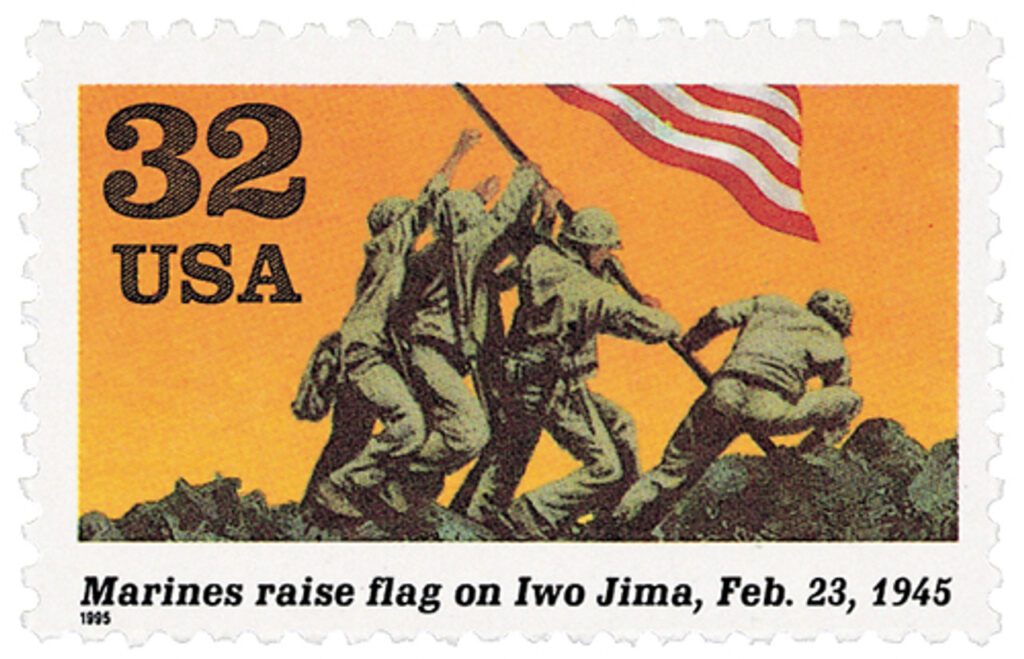

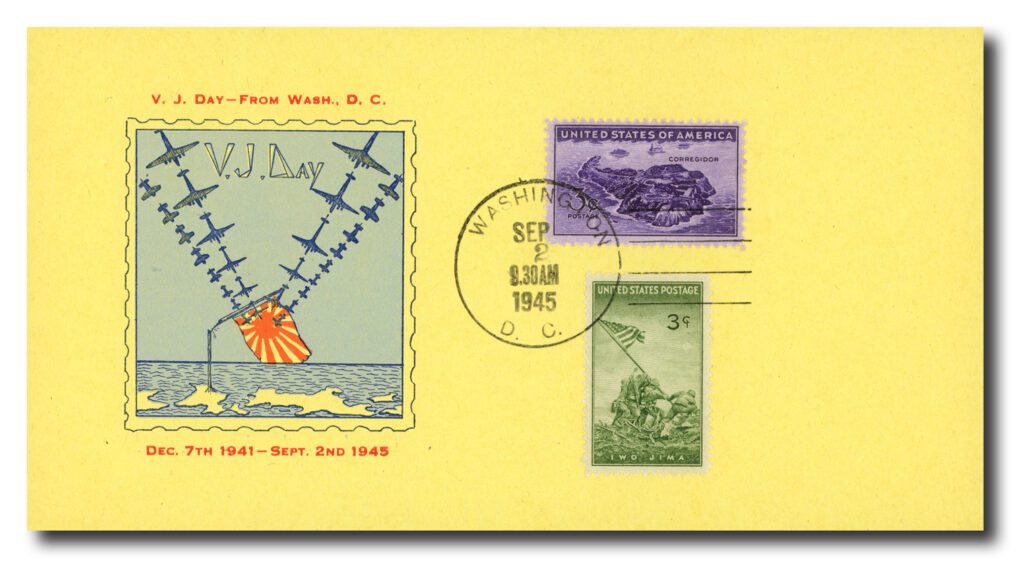

The push up Suribachi was slow and costly, but by February 23, the Marines neared the summit. That morning, demolition teams and men carrying flamethrowers destroyed dozens of pillboxes and knocked out enemy batteries. They reached the summit and at 10:20 am and raised an American flag. All over the island, Marines cheered at the sight. However, the flag was small, so the commander ordered an even larger flag, which was raised three hours later. Photographer Joe Rosenthal captured this flag raising in his Pulitzer Prize-winning photo.

The Marines managed to take Suribachi after three days of fighting, at the cost of over 500 men. The early loss of Mount Suribachi was a shock to the Japanese, but they still held a strong position and would hold out for another month. A major turning point came on March 4. On that day, the Marines made major headway getting through the Japanese defenses, forcing Kuribayashi’s main force into a northern cave. It was also that day that the first B-29 landed on the American-held runway.

The American advance resumed on March 6. The Japanese switched to smaller guns, but did not decrease their intensity. At this point, American supporting arms became more effective. Sherman tanks were also fitted with flamethrowers, which many Marines credited as the “supporting arm that won this battle.”

On March 9, the Marines reached the northeast coast, a major victory, but not the end of the battle. The Japanese resistance still held firm for every inch of the island. By March 16, the Marines held about 90 percent of the island, and the Japanese prime minister announced it as the fall of Iwo Jima. American commanders claimed victory and raised another flag over the island, even though fighting continued for several more days. The battle officially ended on March 26, after Kuribayashi took his own life and the Marines overwhelmed the final pocket of Japanese resistance. Even still, the Marines conducted two more weeks of patrols that uncovered over 2,000 more Japanese.

After 36 days of fighting, about 22,000 Japanese soldiers and sailors were dead. The US Marines and Navy suffered 24,053 casualties, of which 6,140 died. It was one of the bloodiest battles of the Pacific War. When news of the high death toll reached America, there was some outcry, but the American military command defended the importance of the island. Iwo Jima would serve its purpose. Between March and the end of the war, 2,251 B-29s made emergency landings on the island, savings the lives of 24,761 flight crewmen that would not have survived without the airstrip at Iwo Jima. One pilot stated, “whenever I land on this island, I thank God for the men who fought for it.” In describing the men that had served at Iwo Jima, Admiral Chester Nimitz famously stated, “Among the Americans who served on Iwo Jima, uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

Truly brave men. We owe so much to the men and women who serve.

Semper Fi.

Hershel Woodrow “Woody” Williams (October 2, 1923 – June 29, 2022) was a United States Marine Corps Reserve warrant officer and United States Department of Veterans Affairs veterans service representative who received the Medal of Honor, the United States military’s highest decoration for valor, for heroism above and beyond the call of duty during the Battle of Iwo Jima in World War II. Williams was the last living Medal of Honor recipient from World War II!

To whom it may concern,

This is such a must read. My 2 grandfathers both were at ww2. Thanks to all who served and got us to where we are today! I hope it’s great for you. Thank you kindly, Marykay

Never should have returned this island to Japan. Too much American blood spilt there. Same goes for Okinawa.

I had an uncle, Robert William Morrison, that was a WW2 Navy dive bomber pilot flying off aircraft carriers. I always wondered how much nerves of steel he had to dive into enemy ships to bomb them when they were shooting all they had at all the dive bombers. It is a miracle he survived these dangerous missions. Great Story. I have these Iwo Jima stamps in mint condition.

Dustin Fuller

Worland, Wyoming