On July 9, 1863, Confederate forces surrendered Port Hudson, ending a 48-day siege.

Henry Halleck, commander of all the Union Armies, told General Nathaniel Banks that President Lincoln “regards opening the Mississippi River as the first and most important of all our military and naval operations.” By May of 1863, the Union Army had gained control of the Mississippi River, except between the fortified areas of Port Hudson, Louisiana, and Vicksburg, Mississippi. As long as the South held that section of the river, the main Confederate supply line from the Western states, the Red River, remained open.

Port Hudson, north of Baton Rouge, was located on a sharp turn in the Mississippi River. Artillery batteries, placed on the 80-foot bluffs, gave the Confederates a clear shot against enemy ships that had to slow down around the bend. The South realized the importance of holding the river and began building up fortifications in August 1862. Major General Franklin Gardner, commander of the fort, ordered more earthworks to be built, improved the roads, and increased the efficiency of moving and storing supplies.

In December, Union Major General Nathaniel Banks arrived in New Orleans with his 30,000-man Department of the Gulf. Banks had earned his rank because of his political connections rather than military talent. The commander was hesitant to attack the heavily guarded fort up the river and spent months in preparation. He was finally prompted to act when he heard some of his troops would soon be sent to aid Grant in his Vicksburg campaign.

Banks’s plan was to divide his army into two groups and attack Port Hudson from different directions. Three divisions approached from the northwest, while two advanced from the south. By the evening of May 22, 1863, Union forces had arrived and were encamped around the four-and-a-half-mile Confederate fortifications.

Banks believed he could easily overpower the Confederate force of 7,500. His intent was to force a quick surrender, then join Grant in his Vicksburg campaign. The night before the attack, Banks met with his generals and ordered a simultaneous assault from four groups. He did not set a specific time to begin the attack, instead telling them to “commence at the earliest hour practicable.”

The attack began at dawn on May 27. The US Navy bombarded the fort from the river, while artillery fired from the Union encampment. Charges began to the north, but Union troops were stopped by crossfire from three Confederate fortifications. With regiments unable to move, the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards were called upon to assist. Made up of free Black men and the formerly enslaved, this attack marked the first time African Americans saw combat. They fought hard but were forced to retreat. The fighting in the northern part of the fortress ended by noon. Through the remainder of the day, the Confederates repulsed the Union Army’s uncoordinated attacks.

The lack of success and high casualty rate convinced Banks he needed to plan for a siege. He ordered his men to begin digging trenches, allowing his army to get closer to the enemy. When reinforcements arrived in early June, Banks decided to make another attempt at forcing the Confederates to surrender. After bombarding the fort on June 13, the commander demanded surrender, but Gardner refused. The next day, the Union troops attacked the fort, resulting in more casualties. As the heat of the Louisiana summer intensified, both sides remained active. On the Union side, tunnels were dug under Southern fortifications. The mines were filled with gunpowder and readied to ignite on July 9.

Conditions inside the fort worsened. The men had been cut off from all outside supplies and were running low on ammunition and food. They collected spent ammunition to melt down and reuse. The soldiers were forced to eat mules and rats to stay alive and were also subjected to constant bombardment and sniper fire. Their numbers were diminishing quickly because of disease, starvation, and desertion. When Commander Gardner learned of the surrender of Vicksburg, he realized the situation was hopeless. On July 9, the Confederate troops turned the fort over to Union hands, ending the longest siege in American military history.

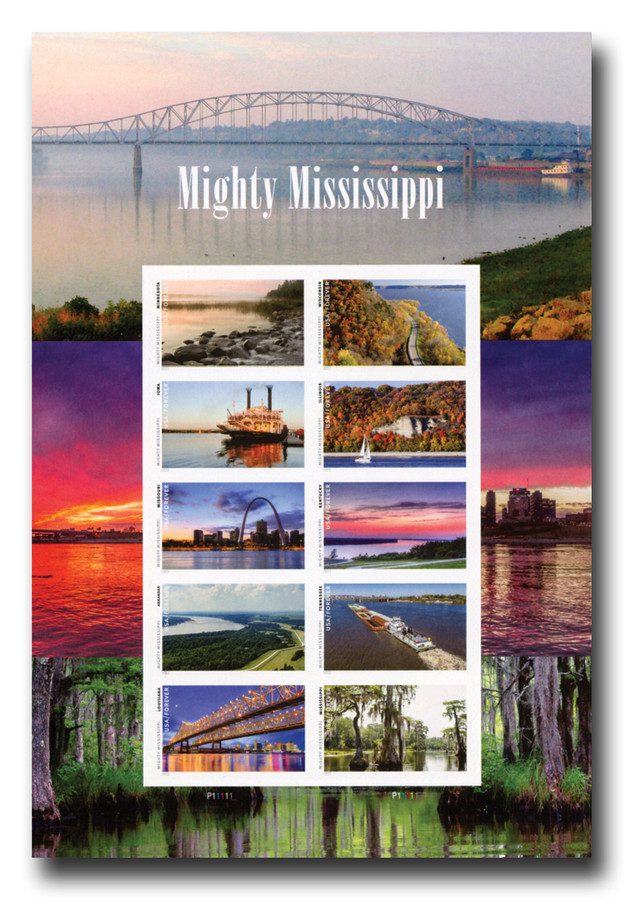

The mighty Mississippi River was now under Union control. The Confederacy was cut in two, severing communications and supply routes from the West. Trade was restored for the Northern states. Their goods could once again be transported down the river and to East Coast and foreign markets. As President Lincoln announced, “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea.”

The use of Black regiments proved their bravery in battle. One captain wrote, “We shall shortly have a splendid army of thousands of [black troops].” By the end of the Civil War, nearly 200,000 Black Americans had served in the Union Army.

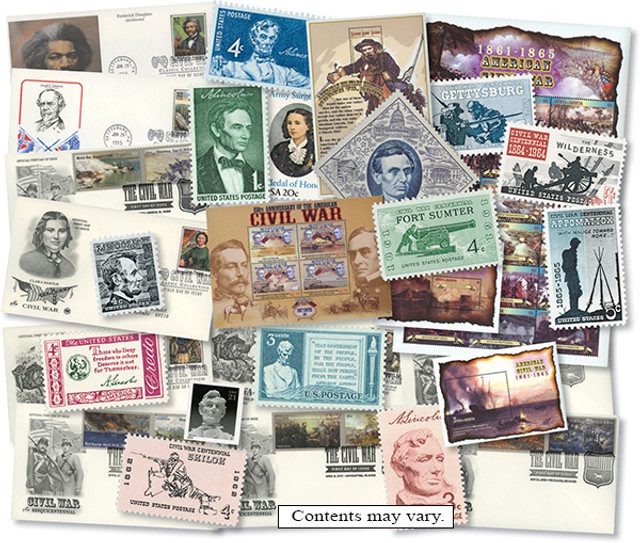

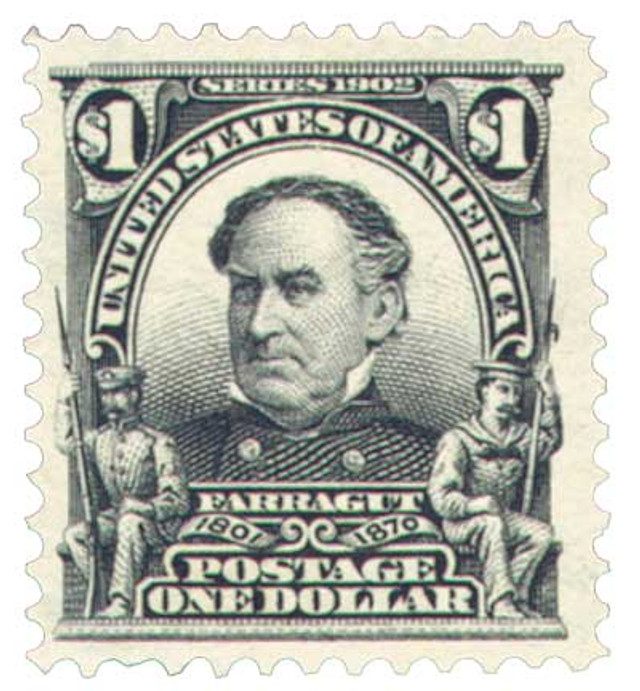

Click here for more Civil War stamps and covers.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

Mystic, as dark as these conflicts were during the Civil War it is important to remind us all of the suffering that took place that in the end resulted in the Union being restored. Interesting reading how Banks was given his rank.

Good article about a little known and appreciated operation of the war. It has been greatly overshadowed by Grant’s brilliant campaign further up the river at Vicksburg, but still merits attention especially for its early use of African-American troops.

To quote the article, “…the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards…Made up of free black men and former slaves…fought with courage.” “By the end of the war, nearly 200,000 African Americans had served in the Union Army.” Thousands more served in the Union Navy. Many thousands were killed and wounded to help preserve the Union. What did they get for this? The formal end of slavery, but nearly 100 years of second class citizenship and Jim Crow segregation.