On June 17, 1898, the prized Trans-Mississippi stamps were issued as part of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha, Nebraska. Because of this, they were sometimes called the Omahas.

By 1898, the western part of the United States was beginning to flourish. Thousands of wagon trains had passed over its mountains, deserts, and Great Plains; transcontinental railroads now linked the West to the East; and many new states had been added to the Union. To call attention to the development of the land west of the Mississippi River, an international exposition was held in Omaha, Nebraska.

The Trans-Mississippi Exposition was held in Omaha, Nebraska, June 1 through November 1, 1898. Its goal was to further the progress and development of the resources west of the Mississippi.

More than 4,000 exhibits showcased social, economic, and industrial resources of the American West. The expo wasn’t a financial success overall, but it did revitalize Omaha, a community that had been devastated by drought and depression.

Over 2.6 million people attended the expo, which featured the Indian Congress, the largest Native American gathering of its kind. Over 500 members representing 28 tribes camped on the fairgrounds and introduced Americans from the East to their way of life. Reenactments of the explosion of the battleship Maine also fueled patriotism and support for the Spanish-American War.

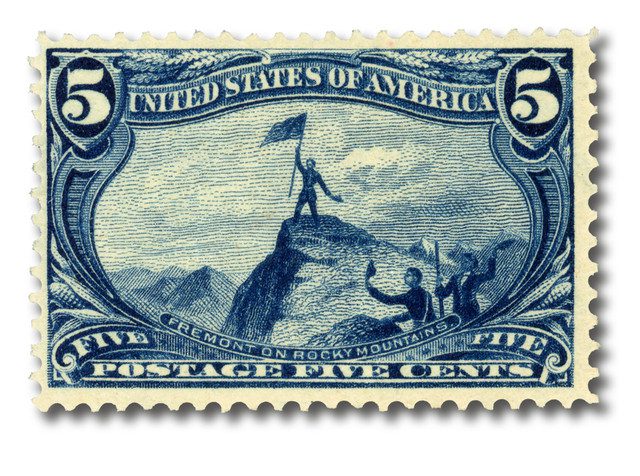

To promote the event, the Postmaster General authorized a set of nine new stamps. The stamps all have the same border design. And rather than including the name or date of the event depicted, they’re captioned with photograph or painting name on which the design is based. The stamps were supposed to be printed in two colors, but the Spanish-American War broke out. Demand for revenue was high, and the Bureau of Engraving and Printing lacked the time and manpower needed to run the two-color press. So the stamps were produced in one color only. Even so, the Trans-Mississippi commemoratives are considered by many to be the most beautiful series ever produced.

The 1¢ “Marquette on the Mississippi” stamp pictures Father Jacques Marquette preaching to a group of Native Americans. The design is based on a William Lamprecht painting owned by Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The 1¢ denomination paid the postcard rate and also was used on overweight letters.

The 2¢ “Farming in the West” stamp pictures a team of horses plowing a wheat field. The design is based on a photograph taken in the field of the Amenia and Sharon Land Company, a 27,000 acre “bonanza farm” in North Dakota. Bonanza farms were very large operations that grew and harvested wheat on a large scale.

The design of the 4¢ Trans-Mississippi stamp was taken from an engraving by Captain Seth Eastman, a soldier who used his considerable artistic skills to capture scenes from the Old West. While assigned to Fort Snelling in Minnesota, he amassed a portfolio of paintings devoted to the study of “Indian character, and the portraying upon canvas of their manners and customs, and the more important fragments of their history.” The painting on this stamp was among them. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s designer and engraver eliminated background figures in Eastman’s original painting and focused only on the racing Indian and buffalo.

The 5¢ stamp depicts “Frémont on Rocky Mountains.” John C. Frémont climbed and raised the flag on one of the tallest peaks in the Rocky Mountains. His ability to draw detailed maps of unsettled territory greatly helped families moving west. He loved adventure and teamed up with Kit Carson more than once to explore the wilderness.

The 8¢ “Troops Guarding Train” depicts a pioneer wagon train winding its way across the prairies, escorted by a detachment of US soldiers. Based on a Frederic Remington drawing, “Troops Guarding Train” is one of the most visually appealing of the Trans-Mississippi series. The stamp was issued to pay the domestic registered mail fee.

The 10¢ “Hardships of Emigration” stamp is based on a painting by Augustus Goodyear Heaton. The 10¢ stamp could have paid the registered mail fee and the first-class rate. The stamp shows a family facing difficulties as it tries to cross America to find a new life in the West. The father in the family is bending over one of the horses as it is dying. Two small children are looking on from the side. The mother, holding a baby, and another daughter are looking out from inside the covered wagon. This image is a reflection of the dangers pioneers faced as they traveled the Oregon Trail. It was also used with other stamps to pay for heavier packages or mail sent to foreign destinations.

The 50¢ “Western Mining Prospector” was taken from a drawing by Frederic Remington, entitled The Gold Bug. It pictures an old prospector, who, with two pack burros, makes his way through mountain country in search of riches. This 50¢ stamp could have been used to pay the five times rate for first class plus the domestic registered mail fee. More often, it was used in combination with other stamps to pay for heavier packages or foreign destinations.

The $1 “Western Cattle in Storm” is considered by many to be the finest stamp ever engraved. It was initially going to be printed with light brown ink, but four days before printing began, the decision was made to change it to black. The design was taken from an 1878 painting by Scottish landscape artist J.A. MacWhirter entitled The Vanguard. After The Vanguard was completed, it was sold to an Englishman, Lord Blythswood. An American cattle company acquired a print of the painting and began to use it as a trademark without permission. Unaware of the image’s origin, the Post Office Department sought the cattle company’s permission to use it as the basis for the stamp’s design. When they learned of the painting’s true origin, the Post Office sent full apologies to Lord Blythswood, who felt no need to pursue litigation. Interestingly, the painting depicts a scene of cattle in a storm in the West Highlands of Scotland, despite being used to represent American cattle on this stamp.

The $2 “Mississippi River Bridge” stamp pictures the Eads Bridge spanning the Mississippi River in St. Louis, Missouri. In the 19th century, this engineering marvel formed a natural boundary between East and West. At the time of its construction, it was the longest arch bridge in the world, with an overall length of 6,442 feet. This stamp was used in combination with other stamps to pay for heavier weight parcels or mail to foreign destinations.

Originally, the Post Office Department didn’t plan on issuing 50¢, $1 and $2 stamps because there wasn’t a big demand for such high denominations. But Postmaster General James A. Gary wanted Americans to know about the achievements of the brave, hardworking, self-reliant people who settled the West. These three high-value stamps were produced after the original series and were on sale for only six short months.

However, collectors of the time protested these high-value stamps. Purchasing a complete set of the previously issued Columbian commemoratives had put a dent in many collectors’ pocketbooks. They resented another high-value set being issued, especially since the high-value Columbians were still on sale at post offices.

But the Postmaster General proceeded with his plans, stating “No one is compelled to buy the high values unless he wishes to do so.” Though sales were brisk at first, purchases quickly slowed to a trickle. By the end of the year the sales were disappointing, so the Post Office Department recalled and destroyed all the unsold stamps.

A century later, modern collectors got the chance to see how these stamps were supposed to be printed. The USPS used the original bi-color dies to print them in two colors as intended.

Click here to view scenes from the Trans-Mississippi Expo.

| FREE printable This Day in History album pages Download a PDF of today’s article. Get a binder or other supplies to create your This Day in History album. |

Discover what else happened on This Day in History.

Providing details of the history of the stamps that commemorate ‘This Day in History’ makes this series much more relevant to collectors. Thanks for presenting these little known facts surrounding the production of these precious historical ‘documents’.

So true. That is also why I love this series.

Great information, however,I enjoy the longer articles

Me too.

Great article on their production with the comparison of the 1998 reproductions.

Another updating and informing essay, this time about the Trans-Mississippi stamps issued. I truly enjoy reading these Mystic articles because they not only improve one’s understanding … and appreciation … about our GREAT Nation’s development thru their informing stamp- history lessons. Thank you SO much, Mystic for enabling us to broaden our understanding and appreciation about the establishment of the single greatest Nation on earth … by OUR Founding Fathers … of the USA !!!

Hardily agree…………….

I think Mystic is doing a fantastic job of merchandising and sharing the history of postage stamps. I love your articles, and particularly this one on souvenir sheets. I once had a very extensive U.S. collection which included an entire mint commemorative collection from the original Columbians through 1970. I also had some valuable covers, including a 5 cent 1847 Franklin, which came from a long hidden collection by the postmaster of New Haven, Illinois. I became a stamp collector at age 7 due to my fascination with the 1938 Presidential series, which initiated my love for history. Thanks to those stamps I knew the Presidents in order long before my classmates. I now regret that I sold everything in 1998, but my spirit was revived by the souvenir sheets you highlight in this posting. I bought all of them, including an uncut full sheet of six Trans-Mississippi reproductions. I had all of these sheets expensively framed and they hang in my office today. I can enjoy them constantly instead of having to go to a lockbox or a book to see everything. Keep up the good work of your reporting.

Sure, do like this series and their representation. Again, they do represent something other than todays “wing-dinging it stamps”. Now the faux stamp market seems to be flourishing, I consider it a great way to own look alike, otherwise never will even see one. So guess what, I even have a counterfeit coin or two of something I never would see in a lifetime. So long as it’s understood about such things and kept within correct context.

Now it has come to my attention a few of the stamp purveyors on here “can’t understand a thing I ever say” with comments… I can’t make things any clearer, too late to change anything these days lol.

Regards, Rich

You do you 👍

These stamps were truly works of art !

I enjoy learning about the stamps and their place in USA history. I also love reading the comments and the different takes on them. Even from years past. Thanks to all

Thank you